‘Black-box thinking’ is what the airline industry deploys to make flying safer and to reassure people it is the safest form of travel. Lessons learnt from past failures become industry-wide protocols.

Unfortunately, REITs don’t seem to learn from their past mistakes, meaning that property valuations continue to be dependent on high and probably unrealistic rental growth assumptions that deny the ‘Brexodus’ risk and the relentless smartphone-enabled rise of online retailing.

In 2007, we called the top of the cycle when REIT shares were down 80% and then we bought back two years later, after which the introduction of quantitative easing (QE) caused REITs to double in value in six months. With REITs now having lost 33% of their value between their peak and the Brexit referendum trough, we thought it might be time to repeal our bear call. However, we maintain that UK commercial real estate and REITs still look expensive.

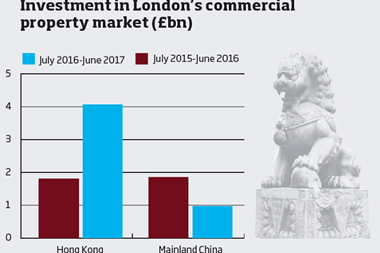

The Great Wall of Money is losing momentum. US money can’t get its credit leveraging and sovereign wealth money has lost pricing power with weak oil prices. Korean and Malaysian money tailed off in 2016, which leaves the money coming in from China routed via Hong Kong.

Even that Chinese money now comes with a regulatory risk from Beijing. State Council guidelines state that: “China will restrict domestic companies from investing in sectors such as real estate, hotels, the entertainment industry and sports clubs.” The question is what impact this is likely to have on UK investment.

Find out more: How much will controls limit Chinese investment?

The Cheesegrater and Walkie-Talkie buildings were sold at 3.5% against 10-year Chinese government bonds of 3.6%. The UK property market trades at 5.3% (IPD) with 1.1% 10-year gilts (delta: 420bps) and Unibail’s German portfolio trades at 6.8% against Bund yields of 30bps (delta: 650bps).

Aberdeen Asset Management’s excellent July 2017 research paper, Mind the (Yield) Gap, suggests that thanks to the UK’s long-term real rental decline, shortening leases, tenants increasingly leaving at the end of a lease and exercising break clauses, taking a property yield and subtracting the gilt yield risk-free rate is naive when the second rent review is increasingly a lease renegotiation.

Entry premium

Our analysis of London office trades shows Chinese money pays a 100bps ‘entry premium’. Foreign direct investment flows tend to trade up in terms of property rights, transparency and land law, which are major factors. If the next influx of investment into the UK is from Germany or Japan, say, then this premium is likely to be a lot thinner.

Meanwhile, the London office market development pipeline is showing little sign of self-regulation. Secondhand availability is soaring but being distorted by serviced office providers as the main market disrupters. We are on the third iteration of serviced office providers having seen Local London in the 1980s, IWG (née Regus) in the 1990s and now WeWork.

This latest challenger, which last month was backed by SoftBank and its Vision Fund to the tune of $4.4bn (£3.4bn), is catering for Generation Y flexi-working and in seven years is already valued at as much as Land Securities and British Land combined. The UK’s traditional ‘25-year let-and-forget’ model is losing pricing power as WeWork cultivates everyone from ‘solopreneurs’ to SMEs without multiple relocations.

The economics, however, remain akin to taking a long lease on an apartment and retailing by the day at a premium to Airbnb. Its defensive qualities are debatable.

Many formerly prime assets are still held at lofty book values with low-gear valuations. Retail is seeing ‘soufflé pricing’ - it adjusted to shorter leases through the global financial crisis but is now seeing rental deflation. The 340,000 sq ft CastleCourt Shopping Centre in Belfast was sold by Hermes for £125m.

This was 30% below the 2011 valuation and large retail parks of more than £100m such as British Land’s Deepdale in Preston and M&G’s Parc Trostre in Llanelli are illiquid.

The UK’s traditional ‘25-year let-and-forget’ model is losing pricing power as WeWork cultivates everyone from ‘solopreneurs’ to SMEs without multiple relocations

As for REITs, shareholders were ordering off the ‘prix fixe’ menu for leveraged beta boys during the global financial crisis and then moved on to ‘à la carte’ for capital recyclers, developer traders and leveraged alpha generators in the real estate market’s QE sugar rush from 2009. With no more insulin, the equity market wants a return to the plain vanilla rent collector and income yield for pudding.

The problem is that compounding works for the REITs that have high cash-generative businesses in sectors detached from the economic cycle and with sustainable NAVs. We continue to favour logistics, student housing, self-storage and social housing as these ‘alternatives’ go ‘mainstream’.

The rest of the REIT sector offers a choice between losing money quickly in London offices or a little more slowly in shopping centres and large retail parks. The REITs are giving money back to shareholders because they think property is expensive, so shouldn’t be perplexed when shareholders dump their stock.

The legacy of free money and very low yields is that depreciation is proportionately more of a problem and a little yield shift goes a long way, which is why REITS still need to minimise gearing.

No comments yet