Industrial property has emerged as one of the strongest performing asset classes this year, apparently brushing off the threat of Brexit as consumers shop - or rather, click - until they drop.

The rise of e-commerce means tenant demand is robust, with record rents being achieved in tightly-constrained urban areas where logistics space is competing with residential.

However, occupiers are having to invest heavily in technology. In a continuing series of think tanks, Yardi Systems brought together a panel of experts to discuss these issues.

OUR PANEL OF EXPERTS

Chair: Claer Barrett, Financial Times

Alan Holland, business unit director (Greater London), SEGRO

Richard Croft, chief executive, M7 Real Estate

Mark Bowden, partner, Caisson Investment Management

Michael Williams, investment manager, M&G Real Estate

Kevin Mofid, research director, Savills

CB: The good news is that we’re seeing healthy yields and rental growth on industrial space, particularly in the Greater London area - but is this mainly because so much of it has vanished in the past decade?

AH: The pressure on land for industrial and urban logistics is immense, particularly in areas of population concentration where developers like SEGRO are competing with house builders. According to the GLA, around 700 ha of industrial land has been lost in Greater London as places like Nine Elms, Old Oak Common and the Olympic Park have become residential areas. That’s the equivalent of seven times the size of Regent’s Park - it’s gone and it won’t be replaced.

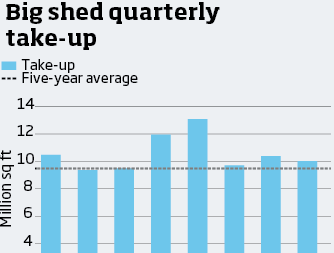

KM: Since 2009, Savills research shows the supply of existing warehousing stock has decreased by 70 per cent. But at the same time, take-up has risen from a long-running average of 18m sq ft per year to 22m sq ft in the past two years.

CB: How much of that increase can be put down to the changing ways in which we shop?

MB: For us, industrial is the new retail - it really is! We are at the start of a seismic shift in the future of retail, and the smartphone is what’s causing the biggest impact. Online shopping accounts for approaching 20 per cent of retail spend in the UK, more if you include click and collect. At the customer-facing end, retailers are spending money on websites; at the other end, they need warehouses that can respond fast.

KM: It’s not just larger buildings that are boosting take-up figures; there is a huge amount of churn at the smaller end of the market. If you look back to 2011, around a third of annual take-up was from the big supermarkets. Today, it’s much more balanced - online retailers, parcel delivery, food producers and the automotive sector. From an investor’s and developer’s perspective, it’s a much healthier place to be.

CB: Does rising demand mean rising rents?

RC: There simply isn’t enough logistics space in London. A property developer friend of mine has just achieved a rent of £26 per sq ft on a letting to a builder’s merchant in Leytonstone - so far as I know, that’s a record industrial rent in London. It’s more expensive than office space in Leytonstone.

MB: We have an estate in Barking, east London, where the rents achieved have gone from £7.50 per sq ft to £14.50 in the space of 18 months.

KM: I did some analysis looking at London deals, and close to 50 per cent of all transactions are to online-type operations. The locations where rents have risen sharply have proximity to the end user - the online shopper who expects delivery yesterday. You have to be near.

MW: This is why M&G try to focus on Greater London and the South East - there is huge rental growth. Of course, the difficulty is we are competing against all of the other funds for exactly the same stock.

RC: And ‘urban logistics’ is now the new buzzword to describe it. I mean, multi-let industrial is so 1980s. There are no yellow stripes on the doors nowadays. I’d go so far as to say that if you can call it ‘urban logistics’, it’s worth another two percentage points on the investment yield. Frankly, the yields seen recently on some ‘big box’ industrial investments have got pretty expensive. Large sheds just haven’t got the rental-growth prospects that urban logistics have.

MB: Some of the supermarket sheds are no longer fit for purpose. They’ve been designed to have big volume distribution going out to stores. But now convenience stores are where people want to shop, and they require smaller and more frequent deliveries that giant depots can’t service.

RC: One of the reasons that M7 doesn’t invest much in big logistics is because we think there’s a big obsolescence risk. We bought a gigantic shed called Mammoth a few years ago, but it had an eaves height of just four metres. That might work well in Lilliput, but today’s occupiers need a much higher eaves height for all their racking and automation. We ended up knocking it down and the site went for residential.

CB: It’s a challenge for investors - but what are the issues for occupiers?

KM: Around one third of the market for existing units comes from third party logistics companies - 3PLs - who transport goods for a variety of retailers and other clients. Profit-wise, that’s a very tight market. I think there’s a danger that rising rents will create an affordability issue for a big part of the tenant base contracted to the retailers.

CB: Is the upshot that online shoppers will have to forget the idea of “free delivery”?

AH: John Lewis recently stopped doing free delivery on click and collect orders worth under £30. The next day, Marks & Spencer announced that they would too. The unintended consequence was that footfall dipped in Waitrose [as fewer customers were going in to pick up click and collect]. It is a big conundrum for retailers.

MB: We haven’t even talked about the reverse supply chain. Solving that is a huge issue. I read somewhere that 70 per cent of online returns are never resold in shops. We have had an inquiry recently from an occupier who takes online returns from different retailers, fixes them if they are damaged, repackages them, and then resells them on eBay. It’s big business.

AH: Our sheds are essentially big shops without customers. As much as 40 per cent of goods going out can come back as returns. Expectations from customers are changing fast. They can buy anything on their mobile phone, and they want it yesterday. Online retailers like Ocado and Amazon are offering guaranteed delivery within one-hour time slots - that’s a huge challenge.

CB: So tenants are faced with having to spend more on rent, but how much money do they have to spend on technology?

AH: One of our biggest tenants is a national department store. For every £1 they’re spending on their central London store fit-out, they’re spending the equivalent of £10 on their logistics platform. Warehouses have to be racked, automated, and the data scrutinised to cut out inefficiencies and drive down waste and costs.

KM: Parcel delivery company DPD is now offering a tracking service that will deliver to wherever your iPhone is. They already send you a photo if they leave a parcel in your porch. And look at the Christmas TV ads from Amazon and Argos last year. They’re not selling a product, as such - their product was their rapid delivery service.

CB: How could developers adapt to these challenges in the market?

RC: One of M7’s biggest investors is a very large Hong Kong family office. They see logistics and industrial going the same way in the UK as it has done out there - I’m talking multi multi-storey. In Japan, there is a 35-storey warehouse. Being an old fashioned shed-head, the thought of this fills me with fear. But in Asia they have to do it like this, as there’s not enough space.

AH: SEGRO owns the first multi-storey shed in the country, X2 near Heathrow, which we acquired through our takeover of Brixton Estates. It’s now fully let with vans flying up and down the ramp all day. But in future, could the upper levels of urban logistics parks in London be used for student accommodation, or PRS?

MW: Mixed use is definitely a good solution. The real estate world needs to adapt to the changes.

RC: The nineteenth-century cocoa and tea warehouses along the river Thames have certainly adapted well to residential use!

MB: Occupiers are also adapting and consolidating. Look at the Sainsbury’s takeover of Argos: that’s a pre-emptive strike in reaction to Amazon Prime. They want the distribution platform.

CB: And finally, with the European referendum ahead of us, how has the industrial market fared?

KM: The only sector that has seen year-on-year and quarter-on-quarter increases in investment volumes in 2016 is industrial. I do think that logistics is more sheltered from what may unfold in the event of Brexit - people still need to eat and shop.

MB: If we vote to leave, overseas capital will dry up. We need to invest in our airports, roads, ports and rail links, but that won’t happen if the flow of capital dries up.

Claer Barrett is the personal finance editor of the Financial Times, and a contributing editor of Property Week

In association with:

No comments yet