What impact will the development associated with these major sporting events have on the country’s property market?

When you think of Brazil the words ‘samba’, ‘soccer’ and ‘sunshine’ spring to mind. So imagine my disappointment when I visited Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo a fortnight ago only to find the country in the midst of a period of sustained torrential rain. All samba and soccer events were cancelled, and as for sunshine - forget about it.

Personal discomfort aside, however, the unseasonal weather conditions neatly sum up this South American nation. Full of contrasts and contradictions, the BRIC member has seen a lot of its citizens get very rich, very quickly, since the country’s economy took off around 2000 and grew by more than 5% a year up until 2012. But on the flip side, it is pockmarked with swathes of poverty-stricken favela that sit cheek by jowl with luxury residential blocks.

To make matters worse, the economy has slowed significantly in recent years and is expected to contract by 2.5% this year. And then last month Brazil was stripped of its BBB-minus credit rating by Standard & Poor’s (S&P) and re-rated BB-plus.

With more than 12 months passing since Brazil hosted the soccer World Cup, and less than a year to go until it hosts the 31st Olympic Games, Property Week assesses what impact the intensive levels of development associated with these major sporting events have had on the country’s real estate market - and whether the legacy will be as lasting as people hope.

It’s fair to say that Brazil’s most famous city, Rio de Janeiro, which was central to the World Cup and will host next year’s Olympics, has endured a chequered history. And with the national economy in the middle of a recession and its debt essentially downgraded to junk status, on the face of it the outlook looks pretty bleak for the former capital city.

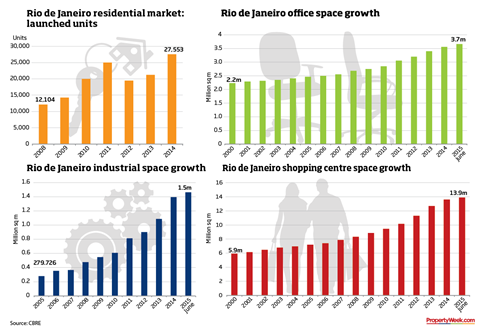

However, this turbulent economic headwind doesn’t seem to have had a visible effect on the property market - to date at least. “In the last two years, there has been a lot of nervous talk around Brazil,” says Carl Ainley, a director at CBRE Brazil. “However, the real estate economy is acting slightly differently. In 2015 we are seeing a considerable amount of foreign investment. Even with the S&P downgrade people are still seeing a future here.”

“Companies like PDG and Gafisa are now in big trouble” - Guilherme Soares, JLL

Guilherme Soares, associate director of project and development services for JLL Brazil, however, takes a more cautious view. JLL’s Brazilian office is involved in a number of major real estate investment projects for international and domestic businesses at the moment, and although Soares remains fairly confident about Brazil’s longer-term prospects, the country’s immediate future concerns him.

“Our market here is not as fast as in other countries, where investors buy and sell rapidly,” he explains. “Pension and investment funds want to be long-term players in Brazil. What’s really worrying is the ‘short-term’ part of the market. Some of our clients are suffering because of a sharp decrease of rents [for office and residential buildings], which are down almost 30% in the last year. We also have high vacancy rates and very low numbers of enquiries.”

These problems have partly been caused by issues in the nation’s oil and gas industry and the ongoing fallout from the scandal surrounding state-owned Petrobras, which saw top politicians accused of bribery and corruption. Companies associated with the oil giant have been adversely affected by the scandal, which has had a knock-on effect on occupier requirements.

Equally problematic is the haphazard approach to property development in Rio. In recent years, a number of family-run property companies have speculatively started acquiring huge swathes of land in and around the city, with no concrete development plans or property expertise.

“The main problem was that in around 2007 and 2008, these companies started to hire professionals who were more from a banking background than from a real estate development background, so they had a completely different mindset and methodology,” says Soares. “Lots of people were buying land, but they weren’t considering whether or not it was in the right location, or the right deal, nor how they would use the land to benefit the economy and the local population.”

When these companies started bringing schemes to the market, roughly around the same time, there wasn’t sufficient demand to support the flood of space. The problem was most acute in residential development, but also affected some office schemes. “Real estate companies like PDG and Gafisa are now in big trouble,” says Soares. “They invested too much and built out too much stock.”

The residential market has also been hit particularly hard by the recession, according to Soares. “Many Brazilians are postponing the decision to buy,” he says. “They often hear that the real estate market is going to drop and prices will reduce in all of the different areas of the city, but they certainly won’t drop like they did in Spain.”

Questions are also being asked about the health of the hotel market in Brazil. The combination of the World Cup and the Olympics next year has led to a flood of development, which brought investment and jobs, but the concern now is oversupply.

“With the World Cup, many middle-tier cities had an important growth in real estate transactions and especially in the hotel and leisure sectors,” says Gilberto Martins, hotel market director at CBRE São Paulo. “But there are also some locations that now are suffering due to oversupply and low occupancy rates.”

Saturation point

In Rio, on the other hand, there is a consensus that the hotel market has not yet reached saturation point. This is partly to do with the upcoming Olympics, but it is also down to Rio’s status as a world city and the number-one point of entry for international businesses in South America. Indeed, some hotels in Copacabana, Ipanema and Leblon boast 90% occupancy rates all year round. “The hotel sector has always been very strong in Rio de Janeiro and is considered the heaven for every hotel operator,” says Martins. “There is still a lot of space for new hotels even inside the city centre.”

That said, investors would still be well advised to act with caution in the area immediately surrounding the main Olympics development. “We are receiving many requests for hotels to be developed in the Olympic area,” he says. “But we are now advising many hotel operators interested in Barra de Tijuca to wait because the possibility of oversupply is really concrete and we need to wait three or four years for the market to absorb all the new developments.”

However, while there are doubts about some parts of the hotel market and residential developers are facing challenging times, in the longer term for office, retail and industrial schemes it’s a different scenario thanks to two large-scale development projects: the regeneration of Porto Maravilha - the local port - and intensive development taking place in Barra de Tijuca.

The Porto Maravilha project is vast in scale, covering an area of the city amounting to nearly 2,000 acres. Plans for the area include offices, cultural and leisure destinations and major transport investment, all aimed at enabling an increase in population from 28,000 people to 100,000 by 2020.

“Porto Maravilha is an exceptional location and it makes a lot of sense for companies to have a presence there,” says Soares. “The area has not been used for almost 20 years for bureaucratic and health and safety reasons. But it has a perfect location with great infrastructure and connections with the downtown and the Santos Dumont domestic airport.”

Inward investment

To boost confidence, a fund has been established to ensure investment in Porto Maravilha is channelled back into the area’s development and maintenance - something that has proved problematic in other parts of Rio.

The Porto Maravilha Real Estate Investment Fund was created by Fundo de Garantia do Tempo de Serviço and is managed by the Rio State Federal Bank, and has effectively taken over services that would traditionally be the reserve of the public sector. It is maintained by the sale of development plots and boosted by licences - Certificates of Additional Construction Potential - that allow investors to buy the right to build additional floorspace that would not otherwise be allowed.

In addition, a new law has come into force aimed both at attracting and guiding development in Porto Maravilha. The law established specific development criteria, particularly with regard to sustainability credentials, but it also offers tax reductions and other incentives that make residential, office and hotel investments less expensive than in the commercial centre.

The strategy for Porto Maravilha appears to be working, with major international brands choosing to relocate to the area. The decision announced in September last year by global cosmetics brand L’Oréal to move its Brazilian headquarters to a 20,000 sq m (215,278 sq ft)building in Porto Maravilha is just one example.

Much of that investment has been guided by inward investment agency Rio Negócios, a non-profit organisation created in 2010 as a public-private partnership between City Hall and the Commercial Association of Rio de Janeiro.

The agency, which was inspired by and has the same structure as London & Partners, was responsible for about $3bn (£2bn) of real estate investment in the first two years of its life. The goal, in addition to promoting closer ties with relevant bodies, is to facilitate the arrival of new companies, and also act as an important resource for the city.

“We answer to the question: ‘Where can I locate my business in Rio?’” says Marcelo Haddad, executive director at Rio Negócios. “We can work with data provided by private companies and with datasets from public authorities to provide the best advice to businesses interested in expanding in Rio de Janeiro, advising them on the best location.”

Rio Negócios also plays an important role marketing the development model being used for Porto Maravilha and many Olympics-related developments. In both instances, the idea is to provide reassurance on the long-term upkeep of a specific geographical area, thereby boosting confidence that investments will grow in value.

“Most of the Olympic projects are being funded by public-private partnerships or concessions,” explains Haddad. “I think we were able to maximise this virtuous cycle of increasing value of the land to make deals with private partners.”

It helps that many office buildings in the traditional city centre are in multi-ownership and are poorly maintained. The result is that many companies are choosing to move out to areas such as the port or to Barra de Tijuca.

“There have been, in the last few years, an important number of companies moving from old buildings to new ones, especially located in Barra de Tijuca, paying almost the same price if not a cheaper one,” says CBRE’s Ainley. “With the completion of the many developments in the area of Barra, we expect to see this movement growing, creating almost another downtown in that area.”

Indeed, the creation of modern, economically and environmentally sustainable districts in Rio lies at the heart of the city’s strategy for the long-term legacy of hosting the Olympic Games. Rio de Janeiro mayor Eduardo Paes, for one, has said repeatedly that the primary interest of the Brazilian Olympic Committee is to make the life of the Carioca - the colloquial name for Rio residents - better.

The new bus rapid transit system and the expansions of the metro, for example, will reduce the journeys of the 60% to 70% of workers who live in the western part of the city by 70%, from an average of two hours, and will remain long after the Olympic crowd has left.

“There is great work regarding the legacy that is behind the Games”, says Nadja de Almeida, Operations Manager and Architect at AECOM, who is part of the team that worked on the masterplan and continues to coordinate the design for the development of Olympic Park at Barra da Tijuca. “The City of Rio and AECOM have always worked towards a vision for the Park post as well as during the Olympics. This is now coming to fruition and it’s great to see how all the investors involved, public and private, are coming with a mindset of transformation”.

In short, despite the economic ill winds, Rio de Janeiro still has much to offer both investors and its citizens alike. Whether it will be enough to counter those ill winds once the Olympics are over remains to be seen.

No comments yet