Beirut’s bold reinvention has been affected by the war in Syria. But amid the gloom there are signs of optimism.

The desert has come to Beirut: cars, buildings and the pavement are cloaked in sand, giving the grey concrete of the city a brownish hue. It’s a few days after a major sandstorm blew in from Syria and the city is still dusting itself down. Beirut is used to such storms and shrugs them off as a temporary inconvenience. There are, after all, much bigger problems blowing in from its neighbour to the east that the city cannot so easily sweep away.

Lebanon’s capital has been afflicted by the war in Syria more than any other - and certainly more than the cities of Europe. The country has taken more than a million Syrian refugees - more than a quarter of its four million population - and is creaking under the strain.

Along with the human fallout, Beirut has been hit by the political instability that has blown in from Syria - Lebanon’s political system is riven with division, generating paralysis that has sparked domestic unrest, and its economy is stagnating as investors take flight.

All of this is undermining the city’s bold plans to reinvent itself after its long civil war: a glut of luxury flats stand unsold; major developments have been delayed or halted; the redevelopment of the city centre is the target of demonstrations; and there are real doubts over the future of a multibillion-pound waterfront development.

We want our city back; it’s not a play thing for developers - Michel, protestor

But amid this gloom and uncertainty, there are signs of hope - and a city reduced to rubble during Lebanon’s long civil war is proving more resilient than one might expect.

At first sight, you would think Beirut was still enjoying a property boom: seemingly every street has a construction site and in the centre of the city, along the seafront, huge towers rise out of the newly laid-out streets.

But appearances can be deceptive. Look beyond the towers and there are signs of rising discord, with graffiti railing against the government and developers daubed across empty shop fronts and construction hoardings.

This dissent is also expressed by thousands of protestors who joined a demonstration in the heart of Beirut last week - one of many over the summer - who are calling for new elections. “We want our city back; this is our place, not a plaything for developers or foreigners, or elites,” says Michel, a student, who joined the protest.

Even the under-construction towers are somewhat misleading. In fact, the bulk of the development began before 2011, when war broke out in Syria and investor confidence evaporated. Since then property sales have slumped.

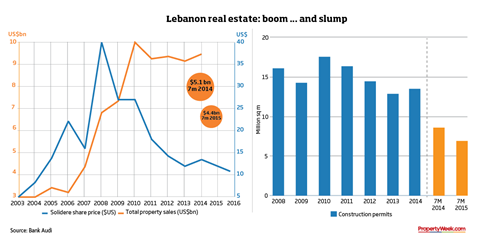

Between 2010 and 2014, they slid from a peak of $9.5bn (£6.2bn) to $9bn and over the first seven months of this year they have continued to fall, sliding by 14% compared with the same period last year, with transaction volumes also down 13.4% over the same period, according to the latest market report from Bank Audi, Lebanon’s largest lender.

Meanwhile, the volume of construction permits, an indicator of new development activity, fell by 23% between 2010 and 2014 - and is down by 19% over the first seven months of this year. “We are in the fifth year of a slowdown in the real estate sector and this year has seen an accentuation of the slump,” says Marwan Barakat, Bank Audi chief economist. “Sales have plunged this year and supply is also falling.”

The dip in the market is all the more pronounced given what came before. From 2005 to 2011, the Beirut market enjoyed an unprecedented boom, with total property sales rising from $2.9bn in 2004 to $9.5bn in 2010 - a jump of 228% - and residential prices increasing by around 25%-30% a year.

The boom was sparked by renewed confidence in the country following the Cedar Revolution in 2005, triggered by the assassination of then prime minister Rafik Hariri, which led to the end of the long occupation of Lebanon by the Syrian army.

“The market was very flat for many years, but in 2005 a wave of optimism spread over the country,” says Fadi Moussalli, JLL head of international capital group, MENA. “Suddenly people were more confident in investing - not only Lebanese but expats from all over the world, who wanted a second home in Beirut, and investors from the Gulf countries, who have always enjoyed coming to Beirut for holidays. There was a big wave of people buying into the city and that drove up prices.”

Rising from the rubble

This boom was primarily focused on the Beirut Central District, a vast tract of land in the city’s downtown area, which has been the focus of an ambitious redevelopment plan led by the developer Solidere (an acronym of Société Libanaise pour le Développement et la Reconstruction de Beyrouth).

Solidere was established by the government in 1994, incorporated as a private business and listed on the stock exchange. The pet project of Hariri, a billionaire businessman before he became prime minister, Solidere is a hybrid public-private entity - a pumped-up version of a UK development corporation - with planning and compulsory purchase powers. It has overseen the development of a masterplan for the nearly 200 ha downtown site that was the heart of historic Beirut before it was reduced to rubble in the 15-year civil war, which ended in 1990.

“The vision was very much to regain Beirut’s position as the pre-eminent global city in the Middle East, which it had been before the war,” says Angus Gavin, who led the development of the masterplan. “It was the one global city in the Middle East then and it wanted some of that back.”

To pursue that vision, the masterplan proposed a mixed-use development, with government, cultural, retail, office and residential functions - with new development sitting alongside the restoration of the old French colonial buildings that originally lent Beirut its identity as the ‘Paris of the East’.

The stars of global architecture were appointed to realise the vision - Herzog & de Meuron, Foster + Partners, Renzo Piano, Jean Nouvel and Zaha Hadid, among others. Gavin, who left Solidere two years ago and now lives in the UK, says over the first 20 years the project was very successful. During that period, more than half the masterplan was built out, including a lovingly restored historic residential neighbourhood, a new government district, a modern shopping centre built on the site of the old Beirut Souks, new office buildings, a new marina and yacht club and an ever-growing thicket of hotels and residential towers.

“It was a real success story - downtown was buzzing and very active and people were very positive about the development,” says Gavin. “Solidere did well financially and was able to drive the residential prices up, which led to the first problems, because local Lebanese were priced out and the boom was driven by buyers from the Lebanese diaspora and the Gulf, who were buying very expensive apartments with waterfront views, but not really living in them - they were just there three weeks a year, that kind of thing.”

Slump or crash?

When the Arab Spring came, and with it the escalating conflict across the border in Syria, interest from overseas buyers rapidly cooled, leaving hundreds of luxury residential apartments without buyers. According to RAMCO, a local real estate consultant, of 65 high-end residential projects completed last year, around 271 new apartments, together worth close to $500m, have failed to sell.

Raja Makarem, the founder of RAMCO, says there is a huge oversupply of luxury flats on the market, and that some developers are now offering discounts of up to 20% off the asking price. “Sales are happening - but not as many and often only with discounts,” he says. “But the drop in price is not tremendous - they’re still making profits, just not as much. This is a slowdown, not a crash.”

That residential prices have not crashed is largely due to developers’ limited exposure to debt, says JLL’s Moussalli, with developers relying on equity to fund projects, both through self-financing and pre-sales.

“The developers are not highly leveraged so they are under less pressure to sell to fund debt repayments,” he says.

“What that means is they can hold on to apartments or they can slow down or delay construction. Time is money, of course, but it’s less of an issue for a developer who is not overly leveraged, so some of them can afford to wait and hope the market recovers. It’s all about ‘extend, amend and pretend’: extend and delay development, amend prices and pretend things are going well.”

Signs of the slowdown in the central area of Beirut abound: a number of high-profile residential towers, including Foster + Partners’ dramatic 3 Beirut, are two to three years behind schedule; construction has halted on the $81m Grand Hyatt hotel project, a great silent hulking concrete frame rising 18 storeys in the hotel district of downtown; and construction has also paused on what was, until recently, Solidere’s

only active project - Zaha Hadid’s ‘iconic’ department store next to the new Beirut Souks shopping centre.

Solidere says the project has been delayed due to “minor modifications in design” and that it will still complete on time in December 2017. But other planned projects, such as Jean Nouvel’s Landmark residential, shopping and hotel complex and a 350-metre tower designed by Renzo Piano, have now been put on hold indefinitely.

Solidere, which has seen its share price fall 44% since 2011 - and 74% since its July 2008 peak - is now focusing on the infrastructure works on the next major phase of the scheme: a huge waterfront development that will, one day, rise out of a vast expanse of stony reclaimed land that stretches out into the Mediterranean.

The slump in the downtown area has been exacerbated by the growing domestic political unrest. The Lebanese parliament, divided between rival factions, has failed to elect a president for 16 months; elections, which last took place in 2009, have been postponed twice.

This has led to growing unrest, with large-scale protests this summer sparked by the failure of the government to resolve a crisis over rubbish collection, which led to mountains of trash piling up on the street.

Despite agreeing a temporary solution last month that saw most of the trash cleared away from central Beirut when Property Week visited last week, the ‘You Stink’ protests have continued, with the focus broadening to wider dissatisfaction with the government - as well as with Solidere and the central Beirut area itself, which is now increasingly seen as an exclusive enclave for wealthy elites. This has meant that security measures around the government quarter in central Beirut have been tightened considerably, with several blocks cordoned off with razor wire.

Ghost town

With public access restricted, as many as 500 shops in the central retail district have been forced to close in the past 10 years, according to Solidere, and in some areas there are entire streets of unlet retail units. Last year alone 80 shops closed, which is around 12% of all the remaining luxury stores in the area, the Beirut Traders Association has said. The Beirut Souks shopping centre (pictured left), which opened in 2010, is eerily quiet, attracting a paltry number of shoppers to its high-end boutiques and luxury retail outlets.

All of this, alongside the residential buildings full of empty apartments and the forest of unfinished towers, has given downtown Beirut a ghostly feeling when compared with the bustling, vibrant and chaotic city that surrounds it. “There really is a very negative view of downtown among the Lebanese now,” says RAMCO’s Makarem. “It is a social disaster. It feels ike a desert.”

Gavin agrees that Solidere’s development has lost its way, but defends the original vision and blames the developer’s execution of the masterplan for central Beirut’s failures. He says that, while the plan was aimed at creating a vibrant mixed-use city centre, Solidere became overly focused on the prime end of the market.

“Beirut was competing with the likes of Dubai and we brought in the star architects to drive this notion that Beirut is an international city and is competing in the global market - so the feeling was you’ve got to do that; you’ve got to bring in these guys. We got a lot of very high-quality buildings built, but maybe it went a little too far,” he concedes.

“It’s now seen largely as for the wealthy; for foreigners. The feeling among the Lebanese is it’s not for us, you know, and that is a problem because historically downtown has always been the only place where everyone, from all Lebanon’s 18 different religions, would mix. That is a very serious problem if Beirut loses touch with that tradition. The centre of Beirut belongs to every Lebanese and they are pretty pissed off with the direction Solidere is taking it.”

But if the development in central Beirut is foundering, elsewhere things look brighter. Karim Makarem, RAMCO director and son of Raja, says another key reason the real estate market has not crashed is that local demand from the middle classes for residential property remains strong.

Makarem says there has been a sea change in the market over the past seven years, with the historic Lebanese preference for large apartments of 350 sq m (3,770 sq ft) or more giving way to much smaller apartments, built along European lines, of 80-200 sq m, which are more affordable.

“Local demand is from middle-income Lebanese and they are end users, not speculators - they are young married couples who need a home,” he says. “And some developers have been catching on to this and are meeting this demand with smaller, more affordable apartments in locations on the fringe of central Beirut. These are selling quite well.”

Indeed, in some of Beirut’s outer locations, the residential market is buoyant. According to RAMCO, prices in Mar Mikhael, an up-and-coming neighbourhood in Beirut’s northeastern fringe with its buzzing café, gallery and night-life scene, rose 21% last year. It is a similar story in other pockets around northeastern Beirut, where some areas have seen rises of 10%-16%.

Local demand has been buoyed by a series of stimulus packages from the central bank, totalling nearly $5bn, which have supported the mortgage-lending market, says Barakat. “The stimulus package has injected a breath of fresh air into the market,” he says. “And it is successfully targeting residents who actually want to buy a home to live in it, rather than selling it after a short period of time to make a quick buck. The growth in the market is in smaller apartments - it seems Beirut will, more and more, catch up with modern European cities, with small flats that cater to the new social dynamics.”

One developer targeting this local market is Capstone Investments, which has three apartment schemes under way in fringe locations - with a fourth, a conversion of an old brewery in Mar Mikhael into loft apartments designed by Lebanese architect Bernard Khoury, in the pipeline.

“That will be, we think, the first development of its kind in the Middle East, and it will be small apartments for young people, says Ziad Maalouf, Capstone chief executive (pictured below). “What we do is choose locations very carefully and seek out great opportunities. There is an oversupply of large apartments so we are providing smaller apartments, but at the same level of quality as the high-end market.”

Missing the boat

Gavin argues that if Solidere is to solve its problems in central Beirut it will need to learn from developers such as Capstone and create a greater mix of apartments in the downtown area. He says he saw signs of the problems with Solidere’s approach to downtown as early as 2007, as the boom was reaching its peak and the local market began shifting to smaller apartments.

“Solidere missed that boat completely; I advised them at the time that they should look at doing smaller sizes on the lower floors - you can still get the same returns as you have three or four apartments in the space of one - but they are still doing those very large, extremely expensive apartments, and the market for those has almost disappeared.

“They need to promote smaller apartments in downtown because you need to get some activity down there - they need to get a lifestyle and young people moving into the area.”

There is still time for Solidere to transform central Beirut into the vibrant commercial and residential centre first envisaged in its original masterplan. After all, the development is just over half complete.

The next phase, which is likely to take another 20 years, is focused on the 73 ha waterfront area, and will include more residential towers, as well as offices and retail and a second marina. Ten plots of land on the site have been sold to developers, but there are few details available on the proposed schemes, other than plans for another Foster + Partners-designed residential tower scheme, being developed by Lebanese firm Mika Land Development.

Capstone’s Maalouf says it is critical that Solidere does not repeat the same mistakes as in the downtown area. “There is such an oversupply of large luxury flats that I think prices will come down - the flats will eventually be sold but there needs to be a demographic shift in downtown and they need to start targeting Lebanese with the new developments.”

The waterfront development will also, eventually, boast a 78,000 sq m public park, running along the waterside, which Gavin says could be a catalyst to bring more local people back into the downtown area.

When Property Week visited, a new concrete promenade had been opened along the waterfront, extending Beirut’s famous corniche, but few people could be seen enjoying its exposed expanse, and the site of the park itself remains a cordoned-off wasteland. Solidere ran a design competition for the park in 2010, and a shortlist of entries was published, but a final design has not yet been announced. “The best thing they could do frankly is build the waterfront park - we ran an international competition for that and they need to build it as there’s such a lack of trust from local people now,” says Gavin. “Beirut is a very dense city so it needs public space.”

Holding tight

When or how long it takes for the waterfront development to be built out - along with the unfinished and on-hold developments downtown - will depend on how the local and regional political development evolves.

Lebanon is resilient and the mood can change very quickly - Raja Makarem, RAMCO

RAMCO’s Makarem says that if the parliament elects a president and the political deadlock is resolved, that in itself could generate a new wave of optimism. The market has proven remarkably resilient, he says, considering that Syria and its horrors are just over 40 miles away.

“Given everything that is going on, what’s amazing is that the market is only stagnating and has not crashed,” he says. “Lebanon has always had problems, but it is resilient and the mood can change very quickly.”

Conversely, the geopolitical situation may not improve and Beirut could continue to suffocate under the blanket of uncertainty, with the market eventually asphyxiated through the absence of investment.

Or worse, the war could spill over into Lebanon itself - and there have been a number of border incursions since the conflict began - shattering the fragile peace the country has worked hard to achieve. If that comes to pass, there will be much more to worry about than a clutch of empty flats. In the meantime, Beirut continues to hold fast, in the face of the storms that come its way.

1 Readers' comment