When the financial crisis hit Iceland eight years ago, Ásta Helgadóttir was 18 and looking forward to university and independence - but then along came Lehmans.

Iceland’s three largest banks failed in the space of three days, the currency almost collapsed, the stock market fell 95% and nearly every business on the island went bust.

Helgadóttir’s father lost his 70-year-old family retail business, his car, his house and his wife. Her mother, a dentist, moved to Norway in search of work; Helgadóttir would soon follow, leaving behind her younger brother.

“This was the human cost of the crisis and it happened to many people,” she says, sipping a coffee in one of Reykjavik’s many buzzing cafés.

“It’s very easy to forget the price people paid - and are still paying.”

Helgadóttir has returned to Iceland and is now an MP for the Pirate Party, an anti-establishment political party that has its roots in the copyright movement.

One of three Pirate Party MPs in the 63-seat Alþingi, she is the youngest person in the parliament. And within months she could be part of a new government.

The Pirate Party has been regularly polling at above 30% - enough to make it the largest party - and with protests continuing in Iceland following the ousting of prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson in April, elections are now expected in the autumn.

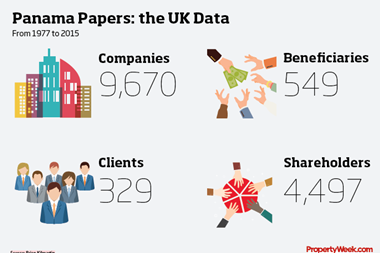

The protests were sparked by the revelation in the Panama Papers that Gunnlaugsson once owned part of an offshore company that held stakes in Iceland’s three collapsed banks.

But Helgadóttir says the anger that is driving the protests points to a more deep-seated discontent in Iceland at how the country’s much-vaunted recovery has failed to work for ordinary people.

“People are angry - they are angry at the established parties and they don’t trust them anymore,” she says. “The Panama Papers set that anger off, but it was there already.”

So what is driving this new discontentment? And how deep does Iceland’s recovery really run?

Political earthquake if Pirate Party take power in autumn

Should the Pirate Party take power, it would be a political earthquake to rival the financial shock the country received in 2008. Iceland was the first country to be hit by the crisis - and few were hit harder.

When Lehman Brothers crashed, its assets were worth around 5% of the US’s GDP; but when Iceland’s three largest banks - Landsbanki, Glitnir and Kaupthing - collapsed their combined assets were 14 times larger than Iceland’s GDP. According to the International Monetary Fund, it was the biggest banking failure in history relative to the size of an economy.

But Iceland was no simple victim of the crisis; it was one of its most spectacular protagonists. In the 2000s, the Icelandic banks grew rapidly by offering people overseas, particularly in the UK and Netherlands, higher interest rates than they could get in their home countries.

Armed with this cash, the bankers, dubbed ‘Viking raiders’, went on an unprecedented shopping spree, buying up assets abroad, including London properties, high-street retailers and even West Ham Football Club.

The bankers were not only buying up assets at inflated prices, they also lent excessively and recklessly, with little regulation. Because Iceland had high interest rates, much of the lending was in low-interest-rate foreign currency, often Swiss francs or Japanese yen; people bought cars and homes with cheap foreign-denominated loans and credit was easy to come by.

‘Wall Street on the tundra’

“I remember going into the bank and the bank manager called me into his office and offered me a one million króna loan; just like that,” says Hörður Torfason, an artist and activist, who sparked what became known as the ‘pots and pans’ revolution, which overthrew the government following the crisis. “Well, I had a long list of questions about that and he wasn’t interested in them - he said, ‘Just take it’. I didn’t, but many people did.”

International traders also piled in alongside many ordinary Icelanders who gave up their day jobs to become traders (stories of fishermen-turned-traders abound). They borrowed foreign currency at low interest rates to buy Icelandic bonds at high interest rates and profited from the difference.

Iceland, a sleepy arctic backwater, with an economy based on fishing, aluminium smelting and tourism - and a population around the same as Cardiff’s - became a centre of high finance: Wall Street on the tundra, as it was dubbed.

Then it all came crashing down. The government could not save Iceland’s banks - they were too big not to fail - and the króna almost collapsed, losing around 50% of its value and leaving citizens with foreign-denominated debt bankrupt. The government acted to save the domestic arms of the banks, securing local deposits, but thousands of ordinary citizens lost their businesses, cars and their homes.

“There was a lot of human damage; people don’t talk about that,” says Torfason. “I had a friend who lost everything and he died soon after of heart failure. Peek behind the curtains and there are terrible stories. People would call me saying they wanted to commit suicide - I would listen to them, then ask them: ‘Do you have children? If you go through with this, how will they feel?’ And they would thank me and say: ‘Yes, I didn’t think of that’.”

Hundreds of UK and Dutch savers in the UK were also hit as Icesave, the online arm of Landsbanki, collapsed and the Iceland government’s deposit guarantee scheme proved worthless. Remarkably, this prompted Gordon Brown’s government to invoke anti-terrorism laws that froze the UK assets of Landsbanki and placed the bank, along with Iceland’s finance ministry, on a list of financially sanctioned regimes that included North Korea and al-Qaeda. This action poisoned diplomatic relations, led to years of legal wrangling (Britain’s savers were finally reimbursed in full last year), and still rankles with Icelanders today.

If in the eyes of the world Iceland was an emblem of the financial crisis, it also subsequently became a poster child of the post-crisis recovery.

‘Miracle’ recovery

Unemployment peaked at 7.2% in 2009, low compared with other crisis-hit nations, and by 2011 the economy had returned to growth. Last year, GDP grew 4% and it is forecast to grow by 4.4% this year - a stellar performance compared with much of Europe. Uniquely, Iceland also prosecuted a clutch of bankers, sending around 30, including the bosses of the three biggest banks, to jail.

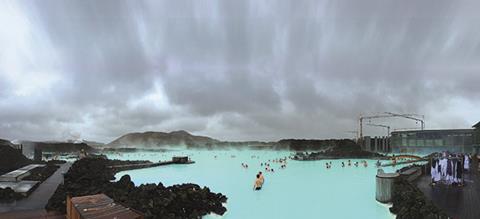

Curiously, Iceland’s ‘miracle’ recovery can in part be attributed to the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull, which caused huge disruption to air travel across Europe. The volcano put Iceland back on the map and is credited by many with sparking an unprecedented tourism boom.

“The increase in tourism was not really the result of any government strategy, although they will say it was,” says Magnus Skulason, managing director at consultant Reykjavik Economics. “We can thank Eyjafjallajökull. It was publicity. People now want to come to Iceland and see the natural beauty.”

With its glaciers, hot springs, volcanoes and incredible landscapes, Iceland has now become a hot destination for short breaks from Europe and for stopovers from the US. The number of tourists increased by an average of 18% a year between 2010 and 2014, and rose 30% last year to 1.3 million. Numbers are forecast to rise to between 1.5 million and two million in the coming years - a huge figure for a country of just 320,000 people.

The expansion is driving a mini-boom in hotel construction and infrastructure, as the country tries to keep up with the influx, and has led to a boost in employment.

Tourism is also driving up house prices as buyers snap up central Reykjavik apartments to rent on Airbnb. After falling by 40% in the crash, prices have risen steadily since and are now close to the long-term average. Last year, prices rose by nearly 10% and Landsbanki forecasts they will jump 25% by 2017, stoking fears of a new price bubble. “It is something that we need to acknowledge and take care over, but it is a recovery from a low base so I’m not too worried,” says Skulason.

It is not just tourism that is driving up prices - asset values are also being inflated by the continued imposition of capital controls, which were only meant to be in place for six months. Unlike Cyprus, where capital controls were focused on stopping withdrawals from the banks, the controls in Iceland were aimed at preventing foreign owners of Icelandic assets, including the creditors of the failed banks, converting their króna into foreign currency. That would have led to the complete collapse of the currency.

The controls froze around £5.8bn in króna-denominated investments and imposed strict foreign currency limits. But they also prevented Icelandic pension funds from investing overseas and around 75% of their portfolios are now invested in domestic assets.

Björn Björnsson, Iceland Chamber of Commerce chief economist, says a healthy ratio would be 50:50 and that by locking money into Iceland, the controls are inflating prices. “If we keep the controls in place for too long, the risk of an asset bubble steadily increases and that will make it harder to lift them,” he says. “So we want to lift the controls before an asset bubble takes hold.”

Last year, the government announced plans to do just that, but the process is slow and fraught with difficulties. Deals have been agreed with the creditors of the failed banks and the next stage is to hold auctions of offshore króna; once that is completed, the controls on businesses, pension funds and individuals can be lifted.

For many, the move cannot come soon enough.

“We are trying to put pressure on the government to lift the capital controls as quickly as possible because we see very real economic damage being done,” says Björnsson.

“We have always advocated a diverse economy, with a broad range of exporting industries to shield us from external shocks. We need the controls to be lifted to allow internationally competitive companies to operate and grow in Iceland instead of moving abroad.”

The Pirate Party’s Helgadóttir is also concerned that the country could once again become enthralled by a single source of wealth; where once fishermen were quitting their jobs to become traders, people are now flocking to open tourism businesses, she says.

“Banks are overexposed to tourism - it is second now to fishing in importance and there is a systemic risk. Tourism can come and go with fashion - we are benefiting now, but what about in the future? We need a more diverse economy so young people have more opportunities than just tourism or services.”

The younger generation is being shut out of the economic recovery, she argues, as rising house prices, coupled with high interest rates make buying a home an “impossibility”.

“Who owns property? It is only people above the age of 35 - society is split between people who own and people who don’t,” she says. “We need to make society work for everyone, not just the wealthy.”

A growing sense that the economy is working only for the elite is driving younger voters to the Pirate Party - more than 50% of under-thirties support the party and it is young people who have been leading the recent protests calling for elections.

After leading the 2008 protests, Torfason, who is now 70, is not involved in the current unrest, but he understands the anger. Gunnlaugsson won power in 2013 after campaigning against foreign creditors and promising to help ordinary Icelanders with debt relief, he says. But people were disappointed by his government and when news broke of his link to an offshore company in the Panama Papers, he became the focus of deep-seated anger that has not been assuaged by his resignation.

“After 2008, we overturned the government and put some bankers in jail, but the same people who were in power are still there and the young people are waking up to that,” he says. “The Panama Papers has opened all that up again.”

At the heart of the recent scandal has been offshoring - and the belief that much of the elite that benefited from the boom managed to escape unscathed from the crash.

“The money all went overseas during the boom, and it is still overseas,” says Torfason. “Offshoring is a major issue - and people are now understanding the seriousness of the situation. Iceland society has really changed since 2008 - and for the better. People are more questioning, more aware - their eyes are open. But there is more to do; it’s like a dance, two steps forward, one step back and a spin. But we are making progess.”

Shiver me timbers

All the anger is currently to the benefit of the Pirate Party - a recent poll put the level of support at 42%. Many in the business and property world worry that the party has a paper-thin policy platform - particularly when it comes to economics and finance. Is Helgadóttir ready for government? “Probably not,” she admits. “But who is? It’s not something that you teach at university. There is no way to prepare for it.”

If her party does come to power, she is going to have to learn fast. Since becoming an international pariah during the crisis, Iceland has come in from the cold. But with the nation braced for a political earthquake and fears growing that its economy is overheating, more shocks could be on the way.

No comments yet