It’s a London thing. Such little supply and such voracious, global demand - a housing crisis, a drastic need for more employment land and one of the world’s biggest ecommerce consumer bases shopping 24 hours a day.

No wonder people are looking high and wide to find space for it all.

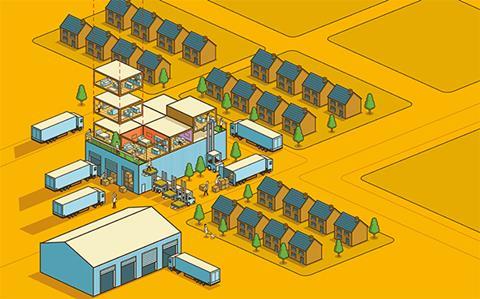

Cue what might just be the solution: ‘sheds and beds’ or, in other words, the collocation of warehousing and residential occupiers next door to, or even on top of, each other. It’s a nascent concept but not entirely new (take a walk behind St Pancras station and you’ll find students living above a Travis Perkins store and delivery centre).

So could this type of multi-storey building be the many-layered answer to the problem of lack of space in London and, indeed, elsewhere in the UK?

Such is the demand for housing that what little space does come to the market tends to go for one use only.

Local authorities want employment space and houses. They have targets to hit for both - Neal Matthews, Strettons

“There is a huge residential requirement at the moment and developers don’t appear to be hitting their targets,” says Len Rosso, head of industrial and logistics at Colliers International.

“Consequently, the commercial sites that do come to the market are often converted to residential use. In the past 12 to 24 months, about 60% to 70% of commercial sites brought to market have been lost to residential use.”

However, housing is clearly just one part of the equation. Look at regeneration plans anywhere in the capital, and the need for commercial space is always there. It is a delicate balance, as Neal Matthews, director and industrial specialist at Strettons, explains.

“Local authorities want employment space and houses. They have targets to hit for both. There are many different aspects to this: housing requirements, logistics, transport and employment. One of the key policies is still employment. Where there is a high demand for both, residential development is more likely to get permission if it has employment space as well.”

Front of the queue

In London, demand comes from all corners of the commercial market, but with ecommerce booming and a race to perfect home delivery, logistics and warehousing are usually fronting the queue.

As Alan Holland, business director of SEGRO’s Greater London portfolio, says, in 2017 “sheds are the new shops”.

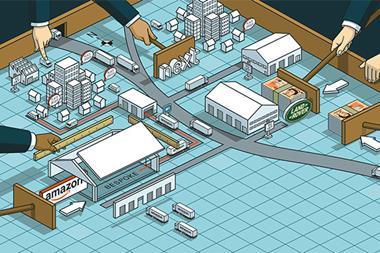

And they need somewhere to go. The need has prompted SEGRO to seek new opportunities in erstwhile unlikely places, even close to the centre of London where residential demand is particularly high.

“We have lots of assets in very dense urban areas and we are looking at a number of opportunities in London,” Holland says. “This could have an impact on sustaining London’s reputation as a thriving global centre. It’s about London’s needs changing.”

One thing causing this new pressure is the fragmentation of last-minute distribution - Seth Love-Jones, TLT

London’s needs are evolving and so is retail logistics, not least because with millions of eager shoppers in town, a new gold rush has emerged with dozens of small start-ups now in the fulfilment market, each hoping to be the next big disruptor in home and on-the-go delivery.

Seth Love-Jones, partner at property and construction consultant TFT, says: “One of the things that is causing this new pressure is the fragmentation of last-minute distribution, which is so split with so many players. But you could argue that this is only temporary - everybody is trying to get ahead in the race. This could, and probably will, be consolidated over time.”

Innovation and expertise

The most headline-grabbing manifestation of this so far is the old Nestlé factory in Hayes, west London. SEGRO is in the early stages of a partnership with housebuilder Barratt London on a mixed-use regeneration project to produce 230,000 sq ft of warehousing space and 1,200 new affordable homes on the same site.

With London councils all facing the same pressures, the demand for more of these hybrid concepts is there, but is the expertise? A new concept of building requires new ways of thinking from planners, developers and occupiers, and lessons will need to be learned.

Peter Higgins, divisional partner at Glenny, says there are issues that developers may not have considered, not least around leasing.

“This sheds-to-beds model is in its infancy and, with very few examples, its success remains to be seen,” he says. “Finding the right occupier will be very important. Developers must also have stringent leasing plans in place - if one occupier leaves, what and who will replace it? The leasing strategy needs to be tight.”

It’s the logistics users who need to be more innovative. Occupiers are going to have to work with more constraints. This is where technology comes in - Richard Sullivan, Savills

LCP Consulting executive chairman Professor Alan Braithwaite adds that while the potential is clearly there, from the property investment perspective the jury may still be out.

“At the moment, the economics aren’t clear. Developers may need a level of public sector sponsorship,” he elaborates. “These sheds also need to be recognised as investment grade. A conventional retail warehouse single-use occupation is something investors recognise and they understand the yield. This is different. Historically, people have been very reluctant to be innovative with their money.”

Savills’ director of industrial and logistics Richard Sullivan says it’s not just the developers and investors who will need to learn new practices but the logistics operators themselves if they’re going to be living side by side with residential.

“It’s the logistics users who need to be more innovative. They will need to consider whether they are disturbing their residential neighbours when running operations at night, so occupiers are potentially going to have to work with more constraints. This is where technology comes in,” he explains.

The question is: when will this cleaner, quieter technology come in? For industrial occupiers to live alongside residential and for it to work, sleeker vehicles might be required that run on electricity or other renewables. There are signs of progress, but no guarantees on timings for widespread adoption - indeed, as things stand, electric vehicles simply can’t manage the loads of large lorries.

Creating a barrier

So with this technology some way off, will tenants want to live on semi-industrial land? While on the surface the thought might not be too appealing, there are solutions being drawn up to create as much of a barrier between the uses as possible.

Sites will need to have separate entrances and traffic flows as standard, according to Rosso. He adds that “there are clever things you can do”, including “screening, acoustic barriers and natural barriers such as fir trees”, to keep things apart.

It is also important not to underestimate the scale of demand for affordable living space. As Rosso says: “People have grown to accept that if you live in London, it’s likely that you’re going to live very close to a bus stop, a train station or a busy road. Why should industrial space be any different?”

All this is going to give a sheds-and-beds scheme a better chance of success, but ultimately the decision comes down to local authorities. Driven partly by intense demand for affordable housing, they are gradually coming around to the idea, believes Sullivan.

It’s interesting to see examples of integrated housing and warehouse developments in London, as these land uses were previously deemed incompatible - James Harris, RTPI

“There is going to have to be some relaxation and some change in their approach. It’ll be interesting to see how flexible and willing they are to adapt. A number of local authorities are trying to go from having discussions about the concept, to seeing how this will be delivered, to then building new projects,” he says.

Like all new concepts in shed design, time and market forces will dictate the future. Sheds and beds are still on the drawing board in most cases. But in London the stakes are high - the borough councils, City Hall, developers, occupiers and aspiring homeowners all know it, as do the town planners.

James Harris, policy and networks manager at the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI), explains: “The RTPI and others have expressed concern that permitted development rights imposed by central government have resulted in the loss of employment and warehousing space in favour of housing, a trend that is affecting London in particular. With space at a premium, it is very interesting to see examples of integrated housing and warehouse developments in London, as these land uses were previously deemed incompatible.”

This balancing act is set to define town planning, especially in London, for at least a generation. With the housing crisis on the agenda at a time when logistics is hungry for space, the sheds-and-beds concept might be the solution everyone is waiting for.

No comments yet