The UK’s craft beer sector is burgeoning - and it needs bigger properties in which to brew more beer.

There’s something of a revolution going on in Britain’s beer glasses. While the Campaign for Real Ale reports that pubs are closing at a rate of 29 a week, the number of breweries is rising fast.

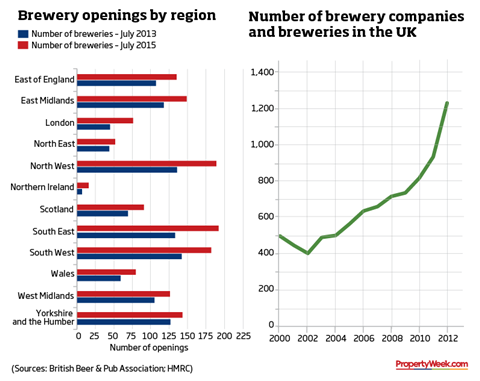

According to the British Beer and Pub Association, a whopping 339 breweries opened between July 2013 and July 2015. Creating weird and wonderful beers with names to match - Smog Rocket, Gentleman’s Wit, Bearded Lady - the craft brewing sector is growing.

For many craft breweries, success inevitably means the need to find bigger spaces in which to brew. Small industrial units - as long as they are in the right location - are often a good solution. “To make more beer, you need more space. All the people I know are looking to expand,” says Jasper Cuppaidge, founder of Camden Town Brewery.

So just how much space is required? And how can the bespoke needs of the craft beer industry be accommodated, especially in areas where demand for space is tight?

Born in the USA

The roots of the UK’s craft beer scene are most definitely in the US, where the sector is well established, accounting for 10% of beer sales (in the UK the proportion is 2.5%).

However, the UK is catching up and perversely the economic downturn was the mother of craft beer’s invention. “During the recession there seemed to be an explosion in craft beer pubs and microbreweries,” says Simon Kelly of Intrinsic Property. “For every decent-sized pub or bar property we had in locations such as London, Brighton, Bristol and similar towns and cities, from about 2010 we’d be getting enquiries from microbrewery businesses - it just seemed to spring up in terms of demand.”

Kelly attributes the growth of craft brewers to several factors: consumer boredom with global brands; availability and reduced costs of pub sites; advantageous tax terms for micro or local beer production; and the entrepreneurial nature of the UK’s leisure industry.

One of the first success stories was Aberdeenshire-based BrewDog , which started brewing in 2007 and now turns over £32m. Other dynamic and growing examples include Beavertown, James Clay and Magic Rock, which alongside Camden Town and BrewDog came together to form trade body United Craft Brewers at the start of September.

What all growing companies need, of course, is space. While Camden Town Brewery’s requirement of 70,000 sq ft is substantial (see box p22), most craft brewers are looking for less space.

“The majority of craft brewers are quite small scale, so the vast majority of demand is for 2,000 sq ft to 5,000 sq ft industrial units, rather than on the Camden Town scale,” says Toby Green, director, industrial and logistics, at Savills, which was called in by Cuppaidge to help him with his search.

One of the dilemmas faced by craft brewers is that they want to stay close to their roots, and finding a suitable site close to home is a big ask, particularly in London. “If there is an old industrial site coming up for redevelopment, it’s likely to go to a higher-value use such as residential,” says Green.

Beavertown Brewery discovered this last year when seeking a bigger space. Originating from De Beauvoir Town in Dalston, east London, which provided its name, the brewer’s first choices were Hackney or Bethnal Green, but it had to settle for an 11,000 sq ft unit further north in Tottenham Hale.

Accessibility is an issue when choosing a site, too. Although these larger industrial sites are used predominantly for brewing, they are also likely to host tasting sessions and welcome punters for brewery tours or to fill up their growlers (half-gallon bottles).

Location was an important factor for Magic Rock Brewery, which moved into its new premises in August. The site on Willow Park Business Centre in Huddersfield, with 15,000 sq ft internal space and the same externally, is close to the town centre, the train station and the M62.

Magic Rock had a long and frustrating search to find its new location. Having found a suitable site in 2013, gained planning permission for the brewing operation and tap room and been granted a premises licence, the brewer’s prospective landlord got cold feet about the tap room at the last minute. The brewer refused to compromise, however, and within six months had found an alternative site just around the corner - and with a landlord that didn’t object to the tap room.

Another issue close to the heart of many craft brewers is sustainability, with the ability to deal with waste from production in an environmentally sensitive manner a key concern. “We need to be able to look after the water on the way out,” says Camden Town’s Cuppaidge. “We want to be as environmentally friendly as possible. That makes sense from a financial perspective, but also from a human perspective.”

Room to grow

However, perhaps of most concern to successful craft brewers is finding sites that will allow them to scale up operations quickly.

Meantime Brewery, which was bought by brewing giant SABMiller in May this year for an undisclosed sum, initially had two units on the Lawrence Trading Estate in London’s SE10, then took another and may look for more, as it pursues an ambitious £4m expansion plan.

“We have an 18-month project involving tanks and new brewing kit to make sure we can produce enough beer to meet demand,” says chief executive officer Nick Miller.

With such investment in brewing equipment, Miller’s advice to fledgling brewers looking to lease property is to consider carefully what might happen when a lease expires. “You need to know that when you get to the end of your tenure, you are not going to be booted off site,” he says.

There are some craft beer enthusiasts who see Meantime’s decision to sell to Miller as a betrayal. Craft beer, they argue, is all about independence and doing things differently from the mainstream brands.

However, craft doesn’t have to mean small. One of the most revered US craft brands is one of the biggest: Sierra Nevada, founded in 1978, whose sales now top $200m (£130m). It is with such examples in mind that UK craft brewers are plotting their expansion.

Camden Town Brewery

Jasper Cuppaidge, founder of Camden Town Brewery, personifies the UK’s burgeoning craft beer sector: entrepreneurial, energetic and not an inch of beer belly.

Like many of his peers, Cuppaidge began brewing single-handedly in the basement of his pub seven years ago, starting a brewery proper in a railway arch in Camden in 2010. Having grown its revenue from around £900,000 to £9m in three years, Camden Town Brewery now employs 90 people - a number that is expected to rise to 150 in a year’s time.

So successful has the brewery business been that Camden Town has been forced to contract out more than half its production to a brewery in Belgium. Now Cuppaidge is looking for a new site so he can bring all the brewing back to the UK.

The company has identified a preferred option with the help of Savills: a 25-year lease on a 70,000 sq ft industrial unit in Enfield, with rent thought to be around the £9/sq ft to £10/sq ft mark. However, at the time of going to press, the deal had yet to be signed.

Presuming it goes ahead, the location represents a compromise for Cuppaidge. “We desperately wanted to stay in Camden. We tried every angle, but nothing was available.” However, moving outside the borough allows the brewery to afford a site that is 40% to 50% bigger, allowing for future expansion.

One challenge in securing a property for Camden Town Brewery - and for others in this sector - is covenant. “To even be able to qualify to take these sites, you need a good covenant,” says Cuppaidge. “When you are a small business, that’s something you probably don’t have.”

Camden Town’s solution was crowdfunding. It launched its Hells Raiser campaign this March with a £1.5m target and managed to raise £14.5m, £3m of which came through crowdfunding and the rest from a private investor. “It is a very capital-intensive investment,” says Cuppaidge. “It does not come cheap. To grow, you need customers but you also need capital.”

Crowdfunding also has promotional benefits, not least the 50 articles or so that were written on Camden Town’s campaign. “Now we have 3,500 ambassadors who will buy our beer and promote it to their friends,” says Cuppaidge

No comments yet