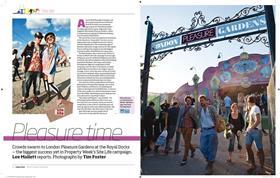

London Pleasure Gardens was supposed to harness the Olympic spirit for Newham. Instead, it went into administration before it could take off. Mike Phillips reports.

£120,000. That is what Newham Council last month paid for a company and site into which it had pumped more than £5m, and where other creditors will lose more than £2.6m.

The numbers contained in a report from the administrators to London Pleasure Gardens are stark. The company owned a lease on and operated a previously disused site in the Royal Docks in east London, which was intended to be brought back to life and bloom during the Olympic summer.

Instead, it went into administration within six weeks of opening, unable to even begin to meet its ambitious business plan.

Property Week was involved with the scheme, supporting and promoting the Meanwhile London competition run by Newham Council and the London Development Agency to find temporary uses for unused sites in the Royal Docks. Much fanfare and back-slapping heralded the opening of the Pleasure Gardens, but the scheme’s life was even more fleeting than originally envisaged.

As the dust — one of the major problems with the site, as it turned out — settles, the ultimate cost of the failure becomes apparent. More than £5m of public money was pumped into the site, and this looks unlikely to be recouped. A further £2.63m is owed to unsecured creditors, among them local businesses, which will never be repaid. And the issues encountered in the creation the London Pleasure Gardens damaged the reputation of “meanwhile” uses of vacant land, at a time when such uses are more vital than ever.

Although the money might never be repaid, lessons from the episode might alleviate some of the reputational tarnish.

The site was essentially meant to be unfinished ahead of opening

The Meanwhile London competition was intended as an innovative and ambitious initiative to bring land that had lain disused for years back into public use, tapping into the once-in-a-lifetime boost in interest and influx of visitors the Olympic and Paralympic Games would bring to east London.

Proposals for four sites in east London were sought by Newham Council and the London Development Agency, in a competition promoted by Property Week as part of its award-winning “Site Life” campaign to find uses for vacant land (box, below). The largest site was a swathe of Silvertown Quays in the Royal Docks, between Pontoon Dock and the Excel London centre.

Winners were chosen for the four sites and the London Pleasure Gardens proposal bagged the largest site. The idea was to create a cultural venue that would host music festivals, comedy and other live events. A dome structure with a capacity for 1,000 people began to be erected from March 2012, alongside a tent-like building with capacity for up to 2,800 visitors. Overall site capacity was expected to be up to 25,000.

London Pleasure Gardens Ltd was created and granted a short-term lease on the site until December 2014, with a break in October 2013.

The directors were all from the live events and “Meanwhile” scene: Deborah Armstrong, who was the creative director of the project, Robin Collings, John O’Sullivan, and director of marketing and audience development Garfield Hackett.

The business plan for the company had two main strands. The first was to generate revenue from hosting events, including income from food, drink and ticket sales.

The site was also earmarked as an exit route from the Excel London centre during the Olympics. Visitors would be directed across the site to the Pontoon Dock DLR station to avoid overcrowding at the closer Custom House or Prince Regent stations. A second income stream was to be revenue from leasing pitches to food and drink vendors, who sought to capitalise from this increased footfall.

Newham Council provided an initial £3.3m loan to London Pleasure Gardens to fund the project, of which £1m was for initial remediation works to make the site fit for public access, as it had previously been unused.

However, this was no charity project. The council was to take 20% of the profits, and speaking to Property Week in July 2012 (left), Newham’s head of regeneration Clive Dutton said: “We’re involved in the same way venture capitalists might be, and the return we get on our investment will go towards creating other jobs and ‘meanwhile’ activities in the borough.”

But as it turned out, the project was beset with problems from the outset. Visitors to the opening weekend event, the Paradise Gardens Festival on 30 June and 1 July, complained about a surface that, rather than the garden they envisaged, had a layer of dust that was whipped up by the breeze, and pieces of metal sticking out of the ground that created trip hazards.

Hackett told attendees after the event: “We are building a site where you’ll feel the ‘gardens’ element more and more as we develop. We are adding more rubbish bins, clearer signage, water points, baby-changing facilities and other practical amenities as a result of audience feedback from our opening event.”

The initial contamination of the site, and the £1m spent to make it fit for the public, had proved to be vital — it was a larger than anticipated part of the project’s budget, and took longer than expected to complete. This meant there was less money and time available to make sure that construction of the venues on the site was completed in time for opening.

But things were to go from bad to worse when a subsequent event, the Bloc music festival on 6 July, was cancelled shortly after the gates opened because of overcrowding. Tickets had to be refunded, as did traders who had rented pitches on the site for the event.The company that owned and organised Bloc, Base Logic Productions, also went into administration, and its owners blamed London Pleasure Gardens for the failure.

“In the run-up to Bloc, much of the site remained unfinished, inaccessible or just closed altogether,” Base Logic said in a statement in September last year. As a result, rather than utilising the whole 600,000 sq ft site, the festival had to be concentrated in a small part of it, leading to overcrowding and inability to control the masses of guests.

Visiting time

London Pleasure Gardens’ other potential revenue stream was not going well either. The anticipated flow of people leaving Excel and heading across the site to Pontoon Dock did not materialise, as visitors were efficiently directed to nearby stations. Behind the scenes, council insiders argued that the flow of visitors promised by the London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (LOCOG) had not been delivered.

LOCOG replied: “Sensible business planning to allow the DLR to cope with a large influx of passengers during the Olympic events at Excel meant that temporary limitations on promoting the Pleasure Gardens at games time were agreed with the venue at the outset and would have been factored into their business model.

“LOCOG has certainly been encouraging spectators choosing to leave the Excel centre that way to make use of the Pleasure Garden facilities.”

All this meant that, within a month of opening, a winding-up order had been served against London Pleasure Gardens Ltd by creditors, and on 8 August, partners from Deloitte were appointed administrators to the company. A sales process was commenced to try to find a buyer for the company and its lease, with 10 parties signing non-disclosure agreements and one making a formal offer. However, this was of a nominal amount, and the council has now bought back the company and lease for just £120,000.

Meanwhile projects are incredibly important, because they can have an influence on the entire area

John Burton, Urban Space Management

At the date of Deloitte’s appointment, Newham Council was owed £4.1m, and post-administration it also ploughed in another £1m to try to keep the site operating and fund ongoing costs.

On top of the council’s £5.1m, unsecured creditors are owed £2.63m, none of which will be repaid. Deloitte clocked up £1m in fees, and was paid £400,000, waiving the rest.

Armstrong told Property Week that the issue of contamination had been key, and that the Olympics had been both a blessing and a curse.

“A combination of the lack of the promised Olympic footfall, and the asbestos on site were key issues,” she said. “We were under incredible pressure to get the site ready in time for the Olympics, and then didn’t get the promised footfall, nor were we allowed to open the site up to the general public. An extraordinary amount was achieved in only a few months but the decontamination required meant that both the timeline and the budget for getting the site ready were severely affected.”

Newham Council would not comment on the future of the site, although it is understood to be looking to bring it back into public use with the two venue structures completed.

A spokeswoman said: “We are disappointed that the London Pleasure Gardens failed to bring the planned jobs and visitors to the area. The council is continuing to discuss the future use of the site with relevant parties and remains confident that we will see a return on our investment.”

But the administrators’ report outlines just how underprepared the site was ahead of its opening — essentially, it was always going to be unfinished and the initial trading was meant to support the business while the site was completed.

Deloitte says: “The directors had anticipated that, in the short term, they would be able to generate sufficient short-term funding to complete the site from a number of sources, including additional funding from Newham, income from planned events and trading revenue generated by virtue of the site’s operation as an exit route from the Excel centre during the Olympic and Paralympic games.

“The directors had hoped that this would have enabled the business to continue to trade while the site and structures were completed.”

With a business plan that envisaged the site not being finished when it was opened, some developers have argued that the project was always overly ambitious. Remediation works of £1m are a serious undertaking for any site operator, especially one created in a short space of time, and would have placed enormous short-term pressure on the company.

As an extension of this, to expect an events venue to make back more than £7.5m in less than three years could be seen as incredibly challenging, as such projects almost always make a loss in the short term.

This leads to the wider question of the viability and the legacy of these meanwhile projects.

John Burton, project manager at Urban Space Management, a company that specialises in “meanwhile” projects, explains that the best such projects often start small with limited ambitions and grow to become something bigger and more permanent.

“If you look at Gabriel’s Wharf [on the South Bank], that was created as a temporary project for the Coin Street Community Builders co-op, and it is still here almost 25 years later. Everything you build is temporary or meanwhile in one way or another — look at Broadgate [in the City of London], the original Arup buildings are now being replaced. But you have to have the right approach.

“Building something new is now more difficult, because you have to adhere to building regulations — at Gabriel’s Wharf we were able to use concrete existing garages. It is hard to make a return in the very short term if you have had a big initial outlay.”

Meanwhile, other projects thrive

It was not all doom and gloom for the projects that won the Meanwhile London competition.

The Canning Town Caravanserai, a winning proposal led by architect Ash Sakula, has grown into a thriving part of the east London arts and business community.

It has a similar ethos to the London Pleasure Gardens — the site is used to host arts, cultural and business events — on a smaller scale.

The kiosks and infrastructure on the site were created using reclaimed materials from the Ecobuild sustainability and built environment conference held at the Excel Centre in London every March.

Rather than hosting large-scale events, it is tapping into the diversity of the local community and the current trend for micro-finance to support small businesses.

Recent events include a guerrilla gardening session and garden fete, Spanish workshops and a Diwali evening.

Local traders producing furniture, wooden clocks and skin care products also operate from the site.

Urban Space Management was heavily involved in the creation of Spitalfields Market as part of a joint venture with Spitalfields Development Group, which also began life as a meanwhile space, but is now a central feature of the blossoming area where the City and Shoreditch meet.

“Meanwhile projects are incredibly important, because they can have an influence on the entire area,” he says. “What we did with Gabriel’s Wharf had a big impact on the way Coin Street thought about the [nearby] Oxo Tower, and the revival of Spitalfields will have been a major factor in persuading Allen & Overy to move there [to offices in the adjacent Bishops Square office scheme].”

This is what Newham Council and the London Development Agency were hoping to achieve with London Pleasure Gardens. Whether or not they intended it to be a permanent site — there is no indication that they did — the hope was that an initial boost provided by the feel-good factor of the Olympics would kickstart a vibrant project that would bring back to life a disused site, in turn spreading out into the wider community.

There can be no faulting the intentions, and in the grand scheme of Newham’s budget, which stands at around £300m, £5m is small change.

But poor planning and a business plan that, at best needed everything to go right, and at worst was impossible to achieve, resulted in a missed opportunity to carry the incredible atmosphere created by the Olympic Games into subsequent years. And given that London 2012 was ostensibly all about legacy, that is a big cost.

Source

Photographs by Dimitri Hon

No comments yet