The architect Simon Sturgis also runs a carbon profiling company, SCP, which has undertaken research for clients ranging from Gatwick Airport and SEGRO to the Grosvenor Estate.

The fruits of these labours will be published by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in May in a book titled Targeting Zero: Embodied and Whole Life Carbon Explained.

In the mid-1970s in the wake of the oil price crisis, RIBA’s then president Sir Alex Gordon coined a phrase about environmental design that still resounds today: buildings should be ‘long life, loose fit, low energy’.

Sturgis has in a sense updated this message, taking into account what we now know about the effects of carbon emissions - a far more serious problem than the depletion of fossil fuel resources.

His proposition might be summarised as maximum life, maximum flexibility, maximum reuse and as close to zero carbon as we can get.

A decade ago, his first major piece of carbon analysis uncovered what in retrospect looks obvious, but was certainly not obvious at the time: carbon emissions related to the construction of a building (and subsequent maintenance, repair and change) were far higher than previously understood and were just as important as the energy and carbon associated with operational use.

Coming up with a smart carbon strategy will certainly save costs and increase value

This led to examinations of when would be the most appropriate time to carry out certain sorts of refurbishment and what might be done to improve energy performance as part of the process - what we would now describe as retrofit, ie refurbishment with attitude.

Inevitably, more fundamental questions were then asked about how to take into account carbon issues at the design stage of projects.

One of the virtues of the new book is that it sets out options and ways of thinking about the issues involved in a smart carbon strategy, which will certainly save costs and increase value. Instead of hard-and-fast rules, or a one-size-fits-all approach, Sturgis spells out how to go about analysis, what pitfalls to avoid and the necessity of seeing things in the round.

Testing during development

Moreover, as a practising architect he has been able to test options and ideas in real-world commissions for serious clients who have no need to wear their green hearts on sleeves. For example, for SEGRO he tested the implications of dismantling and reassembling most of a building on a nearby site, as opposed to the simpler strategy of total demolition and rebuild.

For Grosvenor, the task was to examine the outcomes of different retrofit strategies in respect of listed buildings or conservation areas where it would be difficult to make significant visual changes.

Happily he was able to show that considerable improvements could be made despite those limitations and to analyse the benefits of different detailed design and materials strategies.

Working with a client with an interest in the long-term use of buildings was of course a bonus: one of the big issues that concerns Sturgis is the assumption that speculative commercial buildings will inevitably be demolished within 40 years of their completion, with all the carbon implications that involves.

What could be done at the design stage to make it easier for conversion for second or third lives, rather like many Georgian or Victorian buildings?

Even if a building has to be replaced, can it be designed and built for disassembly and recycling (rather than demolition) or better still reuse or (the best carbon outcome) reassembly? This book gives good answers to these questions and they are not simply theoretical.

It also makes some interesting comparisons between buildings including The Shard and the Canary Wharf tower and the relative merits of different cladding systems, especially in relation to leasing regimes.

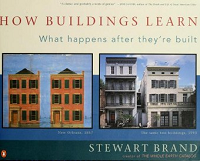

Anyone with an interest in this subject might also like How Buildings Learn by Stewart Brand, which examines why certain building types wear well. Broadly they have a certain spatial and volumetric generosity, robust engineering and design that allows for easy maintenance and repair.

Really it is a simple matter of design intelligence.

No comments yet