The extraordinary row that has played out in Westminster in recent weeks about business rates was no surprise to those in the retail and property world.

The archaic system has been a source of complaint for years but it took the latest revaluation - and, let’s face it, tax rises for the home counties villages frequented by newspaper editors - to push the issue to the front pages and into the House of Commons.

Unfortunately, to no avail as the business rates measures announced in the Budget by Philip Hammond were distinctly underwhelming. The £435m relief package is a small proportion of the £28.8bn that business rates will generate this year for the Treasury.

Meanwhile, the 25,000 small businesses that will benefit from a £50-a-month cap on their increases will still end up paying the new higher rate set by the revaluation eventually and the £300m fund for local authorities to offer discretionary discounts to firms is equal to just £552,000 per council on average this year.

It has been said many times in these pages before, but the business rates system needs a complete overhaul. This is not simply a plea by an industry that feels it is paying too much tax - business rates threaten to affect the make-up of Britain’s high streets, town centre and therefore our of way of life in a way the government has not grasped.

Therefore, this overhaul must go further than simply making revaluations more frequent and switching how the annual inflation-based increase is calculated from RPI to the lower rate of CPI. The overhaul must recognise that the concept behind business rates - that the size and value of a property can be used to calculate economic output - is defunct.

Business rates can be traced back to the Tudors and the Elizabethan Poor Law. Elizabeth I started taxing commercial property as a way to support the poor and eventually help fund local services. It is no exaggeration to say the opposite is true today. Struggling high-street retailers are being taxed while digital companies such as Amazon - which has a market value of more than $400bn (£328bn) - actually see the tax bill for their warehouses fall.

The most expensive tax for many bricks-and-mortar retailers is now business rates. Last year, Sainsbury’s paid £483m in business rates and £117m in corporation tax. That is extraordinary - one of the UK’s biggest companies pays more tax on occupying shops than it does on generating profits. No wonder supermarkets want to expand their online presence. The tax is shaping strategies.

Reshaping the market

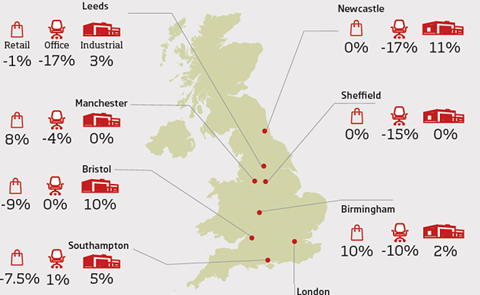

Having said all of this, the recent controversy around the tax has masked how much the latest revaluation could have a positive impact on secondary high streets that have been battered in recent years. What follows is not meant to be a defence of business rates - no tax should have such a profound impact on businesses and whole towns - but it is important to point out how the revaluation could reshape the retail and property market.

Research by the Centre for Cities shows that business rates will fall in all but two cities in England and Wales after the revaluation - London and Reading. In contrast, Blackburn will enjoy a 25% drop in business rates, Blackpool 24% and Newport 24%.

These locations are in desperate need of help, their high streets scarred by empty units. For them, the business rates revaluation is a multimillion-pound package of state aid. It makes their high streets far more attractive for nationwide retailers while new local businesses will start to spring up as they take advantage of the cheaper costs.

London and Reading will face a 9% and 6% increase on average but they are the most prosperous cities in the country in terms of average wages, so are better placed to shoulder the burden of the tax.

Thanks to the revaluation, retail bosses will find over the next 12 months that previously struggling shops are now back in profit while other sites become difficult.

The retail landscape in Britain will look notably different by the time of the next revaluation in 2022.

No comments yet