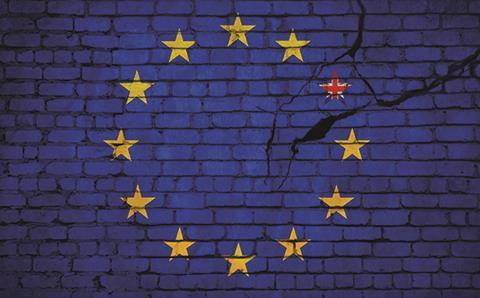

I don’t believe there has ever been such a dramatic shift in the UK property market as we saw in the 24 hours between 23 June (the EU referendum) and 24 June (the announcement of the result).

Not even Lehman Brothers going bust or the bank bail-outs come close, as these events did not change the direction of the market overnight. I therefore have some sympathy for the embattled managers of the daily dealt retail funds who were faced with a new problem on 24 June.

Most sellers of the reasonably liquid equities or bonds on 24 June had a price at which a buyer was willing to do business. However, the manager of a daily dealt property fund in a default ‘business as usual’ mode would have been required to use the cash resources of the fund on 24 June to buy out the sellers on valuations reflecting a parallel universe - with the UK in Europe, not out of it.

The fund’s valuers were not in a position to deliver a Brexit valuation because there was no evidence to support a Red Book valuation. All they could do was produce a historic valuation with a caveat saying that it was not reliable.

Even if the fund was holding enough cash to pay out on this basis, the problem for the manager was an immediate exposure to mispricing - a regulatory sin that could be very expensive to fix given that remaining unit holders would be subsidising the outgoing investors.

The mispricing problem was that no one knew by how much valuations would decline. There was little doubt that prices would fall from those struck on 23 June. In addition, in the immediate aftermath of a market shock, there should also be a liquidity penalty for trading in an extremely volatile and uncertain market.

In hindsight, all property funds faced with dealing on 24 June should have announced at the opening of business that dealings were suspended. The failure to do that opened the door to smart investors to try and exit on a historic price basis.

How multi-asset funds failed

A decision to suspend trading would have been understandable to the investment world: there has still not been sufficient time since the vote for market conditions to settle, allowing managers to price funds appropriately for dealing to take place in a fair and equitable manner for all investors. Instead, liquidity problems were presented by large volumes of investment leaving the sector trying to leave the sector at a pre-EU vote price.

Part of the problem may have been that the volume of the fund flows was magnified by the growth in large multi-asset-type funds that have used the retail funds as a home for their property allocation. When decisions to downweight are taken, the amount of money moving direction can quickly swamp a fund. Not wanting to be behind in the queue can then trigger other investors to seek the exit, making the situation quickly spiral out of control.

The open-ended funds in the institutional market have fared better; as with monthly or quarterly dealings and notice periods for redemptions, the mispricing arbitrage does not exist in the same way. They are not immune to runs on the fund but have more time to deal with redemptions, avoiding market-destabilising fire sales. However, they do not have the right regulatory badge for many of the fund investors.

On most measures, open-ended funds are a much better product than the daily dealt funds, with liquidity measures that reflect the nature of the underlying asset they invest in. It also gives them a significant return advantage as they do not have to hold the same dilutive liquidity buffer. Plus, they do not face the problem of having to sell the family silver in a crisis.

The paradox of current regulation is that retail investors are being directed into daily dealt funds in the interests of investor protection, yet these funds are riskier products than their institutional cousins.

One workaround option for the larger multi-asset funds is to invest in wholly owned property sub-funds that could be managed by third parties if the expertise is not available in-house. This protects the investor from the consequences of actions by other investors. It could be structured to provide the daily dealing and pricing requirements if needed, but the all-important cashflow management that causes problems in the market funds is effectively in the hands of the master investor.

Another option would be for retail investors to make more use of the real estate investment trust market, where a number of companies would be only too happy to grow their asset base. These companies can offer attractive yields, some gearing and more imaginative investment strategies because their permanent capital position means they do not need to hold assets that can be sold on short notice to fund redemptions.

One of the key government justifications for bringing in the REIT regime was making a vehicle suitable for the man in the street to invest in real estate. Maybe it is time for retail managers and advisers to rethink their approach.

I don’t think we as an industry can hide behind Brexit as a ‘black swan’ event. We must put on our collective thinking caps to see what changes can be made to retail funds, as well as looking at alternative vehicles, to ensure redemptions in property funds never again make national news.

William Hill is a director of Mayfair Capital Investment Management

No comments yet