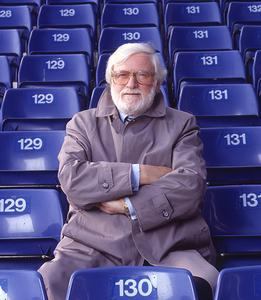

Ahead of the new Premier League season kicking-off this weekend, PW looks back on former editor Giles Barrie’s interview with former Chelsea and Leeds chairman Ken Bates from May 2001.

Having made his fortune in haulage and hotels, Bates was involved in forming the Premier League, the development of Wembley Stadium and is the former owner and chairman of Chelsea, from 1982-2003, and Leeds United from 2005-2012.

Before he sold his stake in Chelsea to Roman Abramovich for £140m in July 2003, Bates spoke to Barrie about the creation of Chelsea Village and bringing an added property element to football economics.

Blue language

Chelsea chairman Ken Bates scoffs at those who question his financial sense – he has a masterplan. The no-nonsense football chief shares his ambitious vision for Chelsea Village with Property Week.

Bates doesn’t mince his words: ‘Ask too many questions and you get told to fuck off,’ he says.

Or, later, ‘You really have your cliché book out today, haven’t you?’ ‘That’s irrelevant shit.’ ‘Do you ever ask a positive question?’

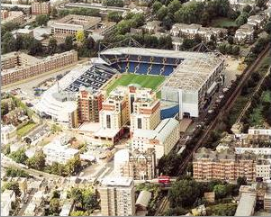

Believe it or not, Bates, now the brain behind a 12 acre, £150m development, is in a good mood today.

The head of Chelsea Village – the quoted company that includes the west London premiership club – is looking forward to ending what he calls the ‘oil exploration’ phase of the operation’s dash for growth.

‘For the first time since 1993, this won’t be a building site. We have spent that time drilling and establishing what our assets are. We’ll start to bear the fruit of eight years’ labour,’ he says.

He has overseen the construction of a 131-bedroom and a 161-bedroom hotel, shops, restaurants, Purples nightclub, 54 flats and a new West Stand with conference facilities and a hi-tech museum.

Critics believe this mix of uses cannot work. They say a hotel and restaurants cannot thrive in a complex that once a fortnight plays host to some of Britain’s most passionate – sometimes violent – football fans. And while many admire the 69-year-old’s tenacity, others who have had dealings with him find him ‘impossible’.

But Bates is determined to prove that a football-based mini-conglomerate on the AIM can thrive in the face of a cynical City and hostile press.

There may be tough times ahead. Catherine Bond, sports and media analyst at Chelsea Village house broker Seymour Pierce, has downgraded her forecast for pre-tax profits for the ‘payback year’ to June 2002 from £9m-£10m to £3m-£4m.

Her earlier estimate had assumed Chelsea would be among Europe’s high-rollers in the Champions League, but a season of under-achievement left Chelsea failing to qualify.

Continued spending on development

In the six months to 31 December 2000, Chelsea Village lost £2.32m before tax. The full year should show an increased loss because of the club’s early exit from the European football scene this year and continued spending on development.

With an interest bill of £6.7m last year and a £75m Eurobond to be paid up in 2007, some say Chelsea Village has overreached itself with its ambitious development plans.

‘Why shouldn’t the Eurobond be paid?’ argues Bates. ‘You have a house – how much is it worth? What mortgage have you got? Are you worried? The answer is no, because you have a big asset and because you have an income that services the debt – same as Chelsea.’

The company’s total assets at June 2000 were £200m, up from £140m the year before, and Chelsea Village’s share price has slumped from a high of 166p to about 40p. Bates shrugs this off as well.

‘It’s not as disappointing as some of the IT companies the clever City piled into last year. We haven’t yet joined the 10% club. Our net assets are 60-70p. Whether or not our share price doubles tomorrow, the assets are there.’

Chelsea Village is where Bates and property collide and the market is assessing whether it will become a real west London leisure force.

Insignia Hotel Partners managing director Derek Gammage says: ‘The issue with Chelsea is that, while it doesn’t look far on the map to get to from central London, it takes a long time. An American tourist is not going to get on the District Line to go there.’

Filling up Fulham Road

But Gammage also agrees with Bates that his hotels are high-quality developments and concedes that people were equally cynical about the City as a hotel location in the early 1990s.

He is impressed by the £90-a-night room rate that is being achieved at Chelsea Village, but less so by the 65% occupancy rate.

Jones Lang Lasalle research shows this occupancy compares with 80% across central London.

Although Bates is not satisfied with this, he argues that once his building site has been cleared occupancy will pick up.

He pins his hopes firmly on the residential conference market, with executives eating in the restaurants, using the health club, touring the ground, possibly visiting the nightclub and buying gifts in his store.

Bates believes Fulham Road is improving.

Pillar Property is building a residential, shopping and retail scheme next door to Chelsea Village,Taylor Woodrow is redeveloping the Lots Road power station into upmarket apartments, and St Georges is shifting £300,000 one-bedroom flats across the road.

If you bring in a franchise, it brings in a manager – and you can always nick its manager. Bit like football, really

Bates is of the opinion that a football club cannot operate just 25 days a year. It is a philosophy he tried to apply to the Wembley redevelopment when he was heading the project, but it would have increased the cost.

‘There’s a load of nonsense written about add-ons at Wembley,’ he says, ‘but it all added up.’

He cites another sports ground, Twickenham, to illustrate his point: ‘If developers had built a wall from the top row of the stand to the ground, they could have cashed in on extra retail or leisure.

‘It’s using space that’s there anyway. What’s interesting is that Coventry, West Ham, Everton, Manchester United, and I think Sunderland are all putting hotels on or near their grounds and they’re all going for conferences and banqueting. It’s the buzz thing.’

The City – and Gammage – believe Chelsea Village should franchise out the running of its hotels to a Sheraton, Radisson or Marriott. This would help cut its £47m wage bill – criticised for being too high, even though it covers the cost of 500 staff and not just its 40-odd players.

It would also help to lure firms that are tied into big chains’ central reservations systems; Schroders, for example, has a deal with Hilton.

Can always buy expertise

But Bates is not the most trusting of characters – after years of bruising battles with TV companies – and scoffs at this suggestion.

He also will not consider selling his hotels, preferring the security of their regular income stream.

‘I remember a hotel in Melbourne that was very good – and then they brought in a franchise that skimmed off the top and off the bottom. Then the hotel owner couldn’t pay the mortgage and went bust – and the franchise bought the hotel off the liquidator.

‘Franchises may have expertise, but you can always buy expertise. If you bring in a franchise, it just brings in a manager – and you can always nick its manager. A bit like football, really.’

His Arkles and Fishnets restaurants have been trading quietly on non-match days, but Bates says lunchtime trade across London is slow.

By contrast, he says, Purples is drawing people from as far away as south London’s Clapham. And, as well as heralding the start of a crucial new season, the autumn will see the opening of a footballing museum, in conjunction with the Science Museum, which will allow people to assess their sporting prowess.

He describes most football museums as ‘stale and jaded – “This is Billy Bloggs’ sweaty sock which he wore on his left foot when he missed an open goal in 1929” – that sort of thing’.

He dismisses the question of whether, say, Arsenal fans, would visit as ‘irrelevant’: 35,000 regulars at another club’s home ground pale into insignificance against two billion potential visitors from around the world.

Wage inflation

However, there are other, more serious issues facing Bates: wage inflation, the threat that TV revenues will plateau and the possible end of the football transfer system.

Again, he is not fazed. ‘Wage inflation does not worry me at all,’ he says.

‘The only time you have to start worrying is when you start spending money you don’t have. Then you go into administration, like Queens Park Rangers.

I only begrudge footballers if they don’t bloody perform on a Saturday afternoon.

‘Chelsea could benefit from the next TV deal [in three years’ time]. Central sales might go.

For the first time since 1993, this won’t be a building site. We’ll start to bear the fruit of eight years’ labour

If it did, we think we would be a beneficiary [of individual sales deals], although we have always opposed anything other than central marketing.’ On the subject of changes to the transfer system, Bates says: ‘By signing [striker] Ruud Van Nistelrooy for £19m, Manchester United has just answered the question. All you have is a typical EU bureaucratic bloody fudge, which is going to make it far more complicated to solve disputes.’

People from property, planning and construction who have had brushes with Bates have had mixed experiences.

Pillar is understood to have discussed a joint venture, but a deal was not struck. In the early 1990s, Bates was embroiled in a war of attrition with John Duggan, whose development company, Cabra, owned the freehold of Stamford Bridge.

Totally underestimating the emotion invested in football, Cabra intended to redevelop the site for residential. In response, Chelsea secured its own consent for football and commercial uses from the Labour council and then complained about the aesthetics of Duggan’s scheme – particularly the bricks being used – to force a public inquiry.

Duggan was driven to distraction by Bates. Having realised the importance of football, he tried to do a joint scheme with Chelsea that would have allowed the club to stay while Cabra added its development expertise.

But Bates struggled to raise the £5m Cabra wanted for this agreement. Eventually, Cabra’s backer,Royal Bank of Scotland, took over Stamford Bridge and sold the ground at a knockdown price to Chelsea.

After all, Stamford Bridge had become an embarrassment to the bank and Duggan had already had his life ruined by football fans calling him at home to abuse him.

Market sneers

Today, the big question surrounding Chelsea Village’s concerns its main shareholder, Swan Management. This offshore company speaks for 26.3% of Chelsea Village and is rumoured to be owned by a South African entrepreneur. Bates, who holds a near 18% stake, knows who is behind Swan but he won’t tell anyone – not even the City.

Last month, the Sunday Times reported that internet tycoon Peter Harrison was planning a hostile bid for Chelsea Village with the backing of the trust responsible for the 20%-plus stake of major Chelsea supporter, the late Matthew Harding.

A takeover is unlikely, given Bates’s control of the company, and he says he is suing the newspaper to ‘punish’ it for misleading those who bought shares on the back of false hopes.

Margaret Casely-Hayford, a partner at law firm Denton Wilde Sapte, who worked with Bates throughout the war with Duggan, says: ‘Ken Bates is a very feisty character. I will never forget how he would pull out of the cupboard every bit of weaponry he could.

‘He knows what he wants. You get very clear instructions and, provided you have done your homework, he’s fine. What he doesn’t like are people who dither. Worst of all are people who don’t meet their deadlines.’

Bates is contemptuous of contractors, whose delays have affected Chelsea Village. He believes English builders use every problem as an excuse, while his new Australian contractor, Multiplex, sees difficulties as opportunities.

Some commentators not only sneer at the Chelsea Village share price but also predict a downturn in the leisure market and a plunge in the fortune of football clubs. To such criticisms, Bates stands his ground.

‘If investment banks get into trouble, that’s not our problem – it’s not our market. People visiting Canary Wharf aren’t going to stay here [at Chelsea Village],’ he says. ‘We are small enough to carve out a niche for ourselves.

‘The other great thing about football clubs is this: if I said to you, “How would you like to invest in a business where 25% of your turnover is guaranteed three years ahead [from TV money], inflation-linked, another 25% you get up front before you’ve opened your shop on day one of the year [from season tickets], there are no bad debts and you have a tied customer base,” you’d say: “I’ll have a piece of that”.

‘The people who can’t run a football club are those who let their supporters’ hearts rule their businessman’s head.’

No comments yet