A year ago today the UK electorate made the now familiar trip to the polling station and took one of the most momentous decisions in our nation’s democratic history.

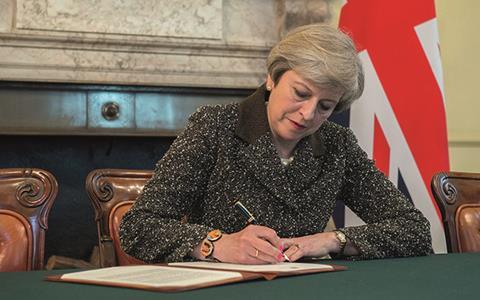

After 43 years at the heart of Europe, a slim majority (52%) proved the pollsters wrong, and took the decision to quit. We were out. Since that decision our political world has been turned on its head. We have lost one prime minster - David Cameron left the business of dealing with Brexit to someone else - and we ended up with Theresa “Brexit means Brexit” May.

You know the rest. Maybot decided a Tory majority of 17 was not enough to give her the authority to negotiate with European Union (EU) leaders for what increasingly appeared like a hard Brexit, and called an ill-judged snap general election. This week she arrived at the EU leaders’ summit in Brussels as the head of a minority government, still scrambling to secure a ‘confidence and supply’ deal with the DUP to bolster her position in parliament.

With the exception of the obvious and too awful to mention events, Brexit has dominated almost every element of government ever since the referendum.

However, a year on we are only just beginning to learn what ‘Brexit means Brexit’ might actually mean. Until this week we have been caught up in a phoney war. What did hard Brexit mean? We were never really told. How hard is it really going to be now May lost her majority?

Well, every time chancellor Philip Hammond opens his mouth it appears to get softer. And what has the impact been on our economy? It’s been mixed. In the property market, some areas, such as logistics are enjoying a good run, while others such as the retail and residential markets have weakened.

Piling into property

However, quite how much of the above can be attributed to Brexit is debateable. One clear impact, however, has been a weakened pound, which has encouraged overseas investors to pile into the UK property market, making up for more cautious and nervous UK funds.

Take the central London office market for example. According to CBRE’s latest research the first quarter of 2017 was the most active Q1 ever for London offices, with a total of £4.9bn in investment trade.

Indeed, the three months to March 31 showed the highest quarterly total since the fourth quarter of 2014, with overseas investors, predominantly from the Far East, accounting for a whopping 80% of all transactions. Nevermind Brexit mean Brexit, in the London office investment world it’s been more like Brexit? What Brexit?

However, in the occupational market, it’s a different story. While take-up of London office was better than many expected in the second half of last year, in recent months, the market has been more subdued and tenant incentive packages have become increasingly generous.

With so much doubt surrounding the Brexit negotiations, many international firms, currently headquartered in the UK are clearly putting decisions on hold over their long-term requirements.

Perhaps that’s the main point. When it comes to the office market, the result of Brexit will only become apparent once the details of Brexit are actually known.

Booming since Brexit

As for other property sectors, some have been booming since Brexit. The industrial and logistics space appears to be one of the most fashionable with investors trampling all over each other to grab a piece of the action.

With our increasing reliance on big sheds holding all the online shopping stock we demand to be delivered the day after, sometimes even the day of, ordering, the logistics business has become an unlikely trend setter. Quite how long this can last as household purse strings are tightened, as families suffer from rising living costs (again partly due to a weaker pound), is worth a question mark at least.

The changing view of how we live in our homes has also encouraged a great deal of investment into the PRS/BTR sector. However, more traditional residential sales have faltered somewhat, with the central London market hitting firms like Foxtons, while the wider UK market is beginning to see a slowing of house price growth in recent months.

There is also the argument, a valid one in my view, that much of the property market had reached its seven-year peak in the run up to the EU referendum, so most of the impact since the referendum has had little to do with Brexit.

Brexit may mean Brexit, but a year on since the UK voted to leave, it seems we won’t know what the true impact is until we know what the deal is. So, for the next 18-months, while talks with EU progress, we will continue with this phoney war. It won’t be until we know the full terms of any deal that we will know the full impact on property.

No comments yet