“You have to be so careful about what you say these days” is an often-heard complaint.

I was reminded of this when interviewing a potential new colleague recently and having to stop myself from asking - just out of interest - his age. “It’s political correctness gone mad,” some would claim.

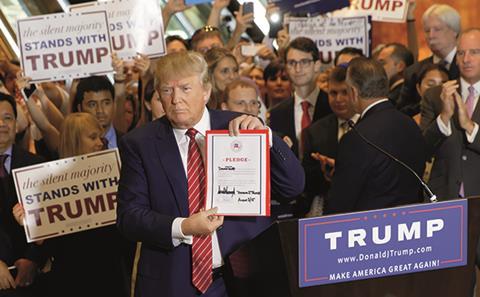

It is ironic, then, that political correctness today seems not to apply to the world of politics. Donald Trump’s recent reference to Syrian refugees as “illegals” or the memory of UKIP’s controversial ‘Breaking point’ poster are two cases in point.

So why are those who should be leading by example so quick to shock and offend by seemingly saying the ‘wrong’ thing?

In a busy world, attention spans are becoming ever shorter, while the speed at which we expect to receive information is getting ever faster and the volume of content we have to wade through via social media, websites, news feeds and more traditional formats is ever greater.

Cheap slogans, extreme rhetoric and shocking assertions seem to be fast becoming an accepted way to make our voices heard and the speed at which we issue responses to others’ opinions gives little time for careful reflection.

Couple that with a love of soundbites and a Twitter-fuelled obsession with summing up stories in 140 characters or fewer and we have a dangerous world where the emphasis is on attention-grabbing headlines rather than proper thought and analysis.

But, perhaps more importantly, we seem to have arrived in a post-political-correctness age where a backlash against carefully considered and sensitive language is in vogue.

Politically incorrect choices

Both the Brexit and Trump campaigns were won on their rejection of political correctness. In a country where we have long celebrated our acceptance of different cultures,

Brexit was not the politically correct choice. In the first debate of the republican primaries, Megyn Kelly of Fox News confronted Trump on sexism, pointing out that he had called women he did not like “fat pigs”, “dogs”, “slobs” and “disgusting animals”. His response was: “I’ve been challenged by so many people and I don’t frankly have time for total political correctness.”

In a refreshingly extensive ‘Long read’ in The Guardian, Moira Weigel argues that political correctness has, in fact, only ever been a negative concept: “If you say that something is technically correct, you are suggesting that it is wrong - the adverb before ‘correct’ implies a ‘but’.

However, to say that a statement is politically correct hints at something more insidious - namely that the speaker is acting in bad faith. He or she has ulterior motives, and is hiding the truth in order to advance an agenda or to signal moral superiority. To say that someone is being ‘politically correct’ discredits them twice. First, they are wrong. Second, and more damningly, they know it.”

The problem, however, is that extreme rhetoric is ruining proper debate and real conversations. One of the main criticisms of the ‘remain’ camp during the Brexit debate was that the immediate reaction to ‘leave’ campaigners was that their views were founded on racism.

Immediately the debate became dominated by language and political correctness rather than focusing on facts and experiences, so an important conversation about immigration never really happened.

As we enter the depths of winter, the same analysis applies to the NHS. The spiralling cost of care, longer lifespans and increasing population are ignored and the critics merely suggest the only answer is money. Dare to suggest a different route and you are branded a destroyer of the system.

Whether tackling international politics or the housing crisis, we have to take extreme language and rhetoric with a pinch - or in some cases a truckload - of salt. Big issues warrant big discussions and we need to be prepared to have real conversations if we want to make a difference.

No comments yet