There are various reasons for the government’s decision to ‘get tough’ on the so-called buy-to-let market by removing tax advantages.

This has, not surprisingly, resulted in howls of what sounds like simulated outrage from some sectors of the market, which seem to be under the impression that the purchase of such units has something to do with the productive economy.

It may have some effect in certain circumstances, but of course there is no direct correlation between this sort of purchase and the construction market. Investors may choose to buy existing or historic stock, and represent serious competition to first-time buyers and those wishing to move gradually up the housing ladder. Giving such investors tax privileges has never made any sense.

However, this is not the same thing as encouraging the construction of homes for the rental market - a far more interesting proposition, and one where tax incentives ought to be applauded. An invited seminar at Mipim, hosted by CBRE, was illuminating for the perspective that players in the market cast on the relationship of the rental market to the housing market as a whole, both in terms of construction and of transactions.

The reality is that this section of supply is small, and is unlikely to ever replace the main UK market, which is the purchase of homes both for living in and as a form of investment for millions of mostly ordinary folk. The proportion of residents who have a mortgage or have paid one off is still more than 60%.

No silver bullet

So those who see the rental market as a silver bullet that will ‘solve’ the housing shortage, in London and the South East in particular, are probably wrong, if you think that strategies work best when they respond to desire rather than impose a solution following market failure. In this respect, the government is on the side of individual purchasers. Hence the endless stream of special arrangements for first-time buyers, a sure sign that the ordinary market is no longer working.

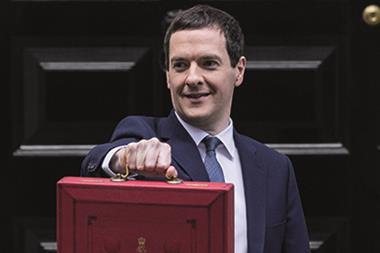

What David Cameron and George Osborne are saying is that they will try to help the sector build for people who want to buy, although they have little to say about the numbers of dwellings likely to be generated as a proportion of the number of households who would like to do so. Once again, as under Mrs Thatcher and Michael Heseltine, there is a greater emphasis on fiscal arrangements than there is on construction itself.

The brutal truth is that the abandonment of a social housing programme has had a dreadful effect on society in general, or at least that part of it that didn’t inherit enough money either to buy a property outright or provide one of those 20% deposits on a dwelling with the dimensions of a large kennel, which seem to get so much applause these days, usually from people who live in luxury conditions.

We will only make provision for the broad population by building more houses, at genuinely affordable prices and rents, on the basis of need and decency, not returns for individuals who like shortage because it promotes the value of their buy-to-let investment.

However, there is a part of the market that likes renting, and this should be encouraged. For many years, it has been apparent that conventional house and apartment design is not suitable for renters, and architects such as Assael have produced large numbers of units where bedroom sizes and disposition, and the general arrangement of space, are aimed at a different market to that being pursued via conventional designs.

Design for rent

This is all about design and construction, not simply investment purchase. The more of it we get the merrier, but it should be in addition to, not instead of, the provision of homes for other parts of the market by both private and public sectors.

I would love to see a Housing Delivery Authority, rather like the Olympic Delivery Authority, with land, funding, planning powers and a shadow construction team - all charged with delivering the homes required in the capital over the next 10 years. All developable land owned by public bodies could be vested in the agency, which would bring in private sector delivery partners, almost certainly not volume builders, who should be going about their business in the normal way.

In short, we should treat housing as infrastructure, institute a military-scale delivery operation and tell politicians to stop making speeches saying everything is under control. Action really should speak louder than words.

Paul Finch is programme director of the World Architecture Festival

No comments yet