It is arguably London’s most lucrative ransom strip, and certainly its best known.

Thirty-five metres wide and wedged impudently within the northern wall of Lord’s cricket ground in St John’s Wood, three railway tunnels have preoccupied the home of cricket since they were sold 13 years ago for just £2.4m.

As the sound of leather on willow marked the start of the first-class season last weekend, it was overshadowed by an absorbing saga of egos andmissed opportunities, former prime ministers and old versus new that has troubled the venerable cricketing institution.

In a month’s time, the 18,000 members of Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) will finally have the chance to help decide the outcome.

On Monday they received a postal ballot form that asked whether they agree with the main committee that proposals to erect luxury flats above the tunnels to fund an ambitious £85m Lord’s revamp should be knocked for six.

If the committee has its way, Charles Rifkind, who owns the tunnels on a 990-year lease and stands to make £100m from the plans, and Almacantar’s Mike Hussey, Lord’s development partner, will once again be forced back to the drawing board.

Ostensibly, the work of dozens of architects, in addition to up to £4m spent designing a full masterplan, could be all for nothing. After a decade

of indecision about how to expand Lord’s beyond 27,000 seats and find new sources of income at a ground used for cricket less than 60 days a year, the MCC appears to be back to square one.

Property Week can now reveal how proposals to expand and modernise the home of cricket have had no tangible outcome and why they could take a radical twist i in the form of a children’s hospital.

Almacantar was picked as the MCC’s development partner exactly a year ago, and offered to pay it £110m in cash, but has been benched by its 20-strong main committee.

And by the end of 2011, club chief executive Keith Bradshaw had resigned, former prime minister Sir John Major had quit the MCC, and the £3m redevelopment plan they had both championed appeared to be in tatters.

Early losses

To find out how this came to pass and predict what will happen next, we must turn back the clock to 1999, to an unremarkable auction where the

MCC made its first - and most fatal - mistake.

That year, the club declined an offer from Railtrack to buy the three tunnels that run beneath the ground’s Nursery End that it had rented on a

140-year lease from the now-state-owned rail network operator.

Lord’s had control of the 1.6 acre surface, but its lease only extended 18 inches below ground level. When Railtrack’s offer was declined, the

head lease on offer went under the hammer.

MCC estates chief executive and ex-Jones Lang LaSalle surveyor Blake Gorst was sent along to bid for the head lease on behalf of the club.

He was beaten by a St John’s Wood resident who did not even sport an MCC tie.

That day, developer Charles Rifkind paid £2.4m for control of the site, and his name has never been far from the MCC committee rooms since.

His Rifkind Levy Partnership swiftly secured development rights and a longer lease of 990 years. Lord’s began paying £130,000 a year in rent.

Rifkind also gained a large stake in the club’s future. The MCC’s lease of the 18-inch layer of ground means it is restricted to erecting temporary

pavilions, and it has been proven that the only way to create value at Lord’s is by marrying its land with Rifkind’s.

Makeshift facilities, delivered in a “piecemeal” way, are disliked both by MCC members and City of Westminster Council, which has spent the past decade calling for a comprehensive roadmap for the entire ground.

To force the point, it will only grant Lord’s temporary planning consents on everything from floodlights to marquees.

In the years following Rifkind’s purchase, the club explored how it could redevelop the ground on its own land, but to no avail.

The situation only began to change in 2006, when outsider Bradshaw arrived from Australia to modernise the club’s image and business.

Unencumbered by memories of that land slipping away - and after realising all other options had been exhausted - Bradshaw established a dialogue and embarked on a four-year competition to realise a 15-year regeneration of the ground.

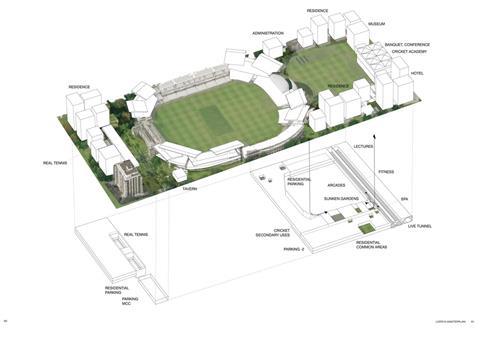

Swiss architect Herzog & De Meuron was chosen in July 2008 to draw up the masterplan Westminster council desired. It produced a thick,

luxurious book called Vision for Lord’s, 250 copies of which were published the following year.

It aimed to mitigate Lord’s cramped passageways, enlarge five stands by a total of 10,000 seats and sink facilities such as cricket nets, shops, and the Lord’s museum into a cavernous public space beneath the Nursery End of the ground.

Funding was to come from 275,000 sq ft of luxury flats on Rifkind’s leasehold land, built by a private developer. At last, the MCC was looking at the big picture and talking to Rifkind.

His logo appeared neatly alongside the club’s famous crest, and he stumped up nearly £1m for the plans. This low-profile developer, who has shied away from the media and declined to be interviewed, had become a joint venture partner.

By 2009, he had joined the top table of the world’s oldest cricket club. The plan he jointly commissioned garnered support from Westminster

council, a former prime minister and the offoce of the mayor of London.

Building a partnership

The following year, the plan was unanimously adopted by the MCC “development committee”, which had been set up to procure a developer.

Its members were pre-eminent - among them, Sir John Major, Lord Grabiner QC, and former England captain Michael Atherton - and it was led

by influential planning barrister Robert Griffiths QC.

What happened next, however, was a slow attrition of the Vision from within. MCC adviser Cushman & Wakefield held a competition to find a developer and, in October 2010, shortlisted Native Land, Capital & Counties, and Almacantar to make more extensive proposals. It also brought on board ex-Grosvenor chief Stephen Musgrave to help assess these bids.

Property Week understands that, as part of the deal, Hussey brokered an exclusive agreement with Rifk ind for a 50:50 split of the residential

sales, believed to be worth more than £100m to each of them. That agreement still stands.

Almacantar’s was the only shortlisted bid that complied with the Vision, as the others proposed to build flats on the MCC’s freehold as well.

So, when Hussey’s scheme was chosen in February 2011, it was unanimously recommended by the development committee to the MCC’s main

board.

He had offered £110m to buy out the club’s lease, which had 125 years remaining. It is thought MCC chief Bradshaw agreed at the time to underwrite Hussey’s costs for working up detailed plans.

But those plans were already unravelling. A source involved in the selection process says: “It didn’t strike me as a well-structured process, and

the [development] committee was railroaded by people with agendas.”

Influential main committee members Oliver Stocken and Justin Dowley have been widely marked out at the ringleaders of the “anti” camp.

When the MCC’s main committee met to discuss the scheme on 16 February 2011, chairman Stocken and treasurer Dowley are believed to have argued that the development committee should be disbanded.

The pair got their way and the committee was dismissed, along with its advisers. Griffiths, the Vision’s chief proponent, was removed from the

main MCC committee.

Dowley set up a new working party of eight people, who were believed to be largely opposed to the plans.

Hussey was encouraged to draw up a more modest scheme, and architect Allford Hall Monaghan Morris was enlisted to design four residential towers on Rifkind’s land.

These distinctive towers diverged substantially from the original Vision, and the so-called undercroft of public space was abandoned.

By the time the plans were discussed at the main MCC committee meeting on 30 November, Bradshaw - the original brains behind the Vision

- had quit and returned to Australia.

Lord’s had also won a contract from the England and Wales Cricket Board that guaranteed at least two tests would be held there each year until 2016.

Tail-end collapse

Rather than Hussey presenting his plans that day, Dowley’s working party showed them to the committee, which rejected them by 18 votes to

two.

The MCC, it said, could now afford to work alone upgrading the ground on an ad-hoc basis - without Rifk ind or Almacantar.

Since then, Hussey has kept quiet, but is threatening to sue the MCC if costs of £750,000 are not reimbursed. Major lambasted the process

undertaken and quit the MCC under a cloud - and then said his reasons for quitting were distorted.

New MCC president Phillip Hodson has written to members, asserting that “the preservation of Lord’s as a cricket ground [is] more important than

a windfall of cash”, while Hussey has been portrayed as a materialistic developer without the interests of the club at heart.

Five years after the Vision was published and 12 months on from Hussey’s recruitment, the original masterplan has little chance of becoming a reality.

Griffiths - its champion - was re-elected to the main committee last month, thanks to support from Major and other supporters of the Vision.

But the idea of giving away control to a developer of luxury flats appears to be dead. Now, Lord’s is believed to be the target of Wellington Hospital,

next door, which proposes to open a children’s clinic on the land, possibly developed by Hussey.

It is also understood that Knight Frank is conducting an upward-only rent review that will likely double Lord’s rent on Rifkind’s land.

Separately, a group of members is rallying for the 180 votes needed to call a special general meeting, at which Almacantar’s revised plans could

be presented in full to members for the first time.

Before that happens, however, they will be asked the following, loaded question: “Do members ratify the decision of the MCC committee not to permit any residential development on the leasehold land at the Nursery End of the ground?”

Members have never once disagreed with the committee during the club’s 225-year history. If they follow form, then the prospect of living within

the walls of Lord’s could remain nothing more than a schoolboy’s dream.

No comments yet