Germany’s open-door policy has piled pressure on a housing market that is already at breaking point.

On a narrow road approaching Frankfurt airport, a small group of people huddle together against the cold. It is windy and snow is in the air. The group, comprising two adults and three children, is slowly shuffling towards the airport terminal around two miles away. I pull over and offer them a lift. As they settle into the back of the car, the kids smile and laugh loudly. The man sits in silence, staring blankly ahead. Despite her best efforts to hold back the tears, the woman, who is wearing a hijab, sobs gently.

“I’m Ahmed,” says the man, after a while. “I’m from a small village near Al Suwar, in northern Syria near the Iraqi border. This is my wife and my three kids. We are so tired.”

Ahmed explains that the family left their home town to escape the heavy fighting between so-called Islamic State and the rebel militia. They travelled 3,575km, crossing the Mediterranean Sea, running across the Greek border and narrowly avoiding capture in Serbia, to reach the relative safety of Germany. “I risked our lives so many times during these months, but we had to go; we had to run away,” says Ahmed.

The hope was to find a better life in Germany. Yet today, he has brought his family to the airport. Why?

“We are going back home. We are leaving this place,” Ahmed responds dejectedly. “There is nothing for us here other than a cold, dirty camp. There is no food; no school for my kids. Only rain, snow and cold. We can’t live like animals. If we have to, I would prefer to do it in my own country and die fighting instead of let my kids die of cold. By going home I am putting my family in the biggest danger in the world, but I don’t see any other solution.”

Ahmed’s experience is not an isolated one. The number of migrants leaving Germany is rising all the time. Airlines are increasing the frequency of flights to Iraq and neighbouring countries to meet demand. People are leaving because Germany is struggling to cope with the humanitarian crisis within its borders, and the resulting housing crisis.

The country faces a major deficit in housing provision – it cannot house all of its own citizens, never mind the many thousands of migrants that have flocked to the country in recent months.

Since German chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to open the country’s borders last August, an estimated 1.1 million refugees from Africa, Asia and the Middle East have entered Germany. This January alone, 91,671 migrants entered and the situation shows no sign of easing, with thousands crossing daily into Germany via its eastern European borders.

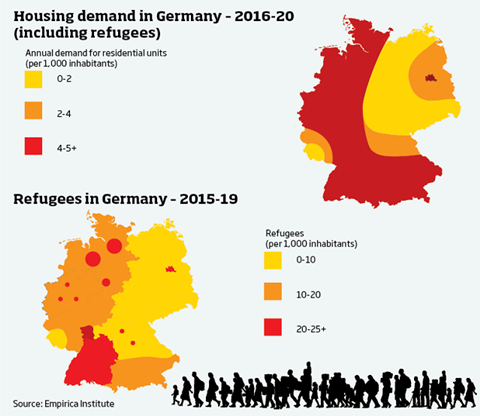

The first official report on the migrant crisis, published last month by the Empirica Institute, predicts the number of migrants who will have received official refugee status between 2015 and 2019 will be around 1.51 million. This will put further pressure on a housing system already at breaking point.

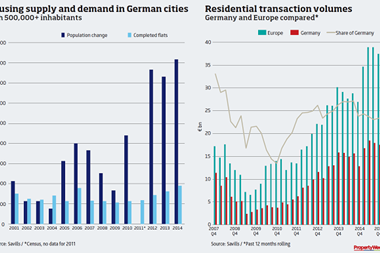

Between 2011 and 2015, the number of people living in Germany rose by more than one million – significantly above government forecasts. In addition to overall population growth, large numbers of people have moved from the countryside to Germany’s seven core cities – one of which, Berlin, has seen its population swell by 40,000 since 2010.

As a result, there is hardly any housing stock available in the major cities. Residential availability was running at less than 2% at the end of 2014 in some locations before the migrant crisis. “The residential market in Germany is now characterised by undersupply in many areas,” confirms Peter Brock, managing director at Grainger Deutschland, shortly to be part of Heitman.

“Building activity in multi-family residential schemes has been low for a considerable number of years and is lagging behind demand. The major markets are very tight. Frankfurt, for example, has nearly zero availability in the residential sector.”

Brock says that with migrants also targeting the major cities, this will inevitably lead to an even greater imbalance between supply and demand. Residential rents have already risen significantly in Germany over the last four to five years. Asking rents have risen by more than 6.5% since 2012, according to the latest Savills market report, and cities with populations of more than 500,000 have seen double-digit growth. Given the current lack of available stock, rents are likely to continue rising.

This may be good news for investors, but it is putting residential property out of the reach of many German families, let alone migrants.

The major markets are tight. Frankfurt has zero availability - Peter Brock, Grainger

“We have a situation where to build multi-family houses and rent these out at an acceptable yield for an investor, the rents that need to be generated must be between €9 and €10/sq m per month, while the average German rent nationwide has historically been between €5 and €6. For a lot of urban and regional markets this is clearly not sustainable,” says Brock.

The problem is compounded by the fact that although development activity has picked up, very little is targeting the affordable housing market. The prospect of that changing is slim. For one, land prices have been driven up by developers competing for space for office and industrial schemes, according to Helge Scheunemann, head of research at JLL Germany.

For another, construction costs have shot up, with the introduction of new energy efficiency laws later this year expected to push them up by a further 7%. “We already have high energy standards, and this new law will put a lot of pressure on the big cities and potentially block off even more of the market,” he says.

Future need

Another reason residential development has been stifled is no one knows for sure how many new houses the country will need in the future.

“This is actually the biggest problem for developers and investors,” says Scheunemann. “Nobody knows what these people [migrants] will do, so they don’t want to run the risk of developing new housing to have it sitting there empty after a couple of years.”

The Empirica Institute estimates that between 2016 and 2020, 656,000 apartments will need to be built to cope with the influx of migrants. Of this, just 43% can be provided by existing vacant flats, meaning 75,000 to 100,000 flats must be built per year. This will drive the total annual demand for new flats from 286,000 to 361,000 units, says Empirica board member Reiner Braun.

With the number of migrants entering Germany growing every day, time is running out. Some initiatives are slowly being introduced to tackle the issue. “Unused sheds and office spaces are being converted into temporary accommodation to absorb the incredible number of people coming in,” says Brock. “However, this is definitely not a long-term solution.”

Perhaps not, but it is better than the current accommodation migrants find themselves in. On arrival in Germany, families like Ahmed’s are directed to refugee camps where they await the official documentation that will give them the right to stay. This takes time. Ahmed waited more than four months, enduring rain, snow and freezing gales at the country’s biggest refugee camp at the former World War II Tempelhof airport in southern Berlin, which houses more than 7,000 people.

Camps like this have been erected all over the country to deal with overcrowding issues. The hospitality industry has also been called into action, with the German government paying independent hotel owners €50 per day per migrant.

As a result, hotel occupancy rates in Germany, which are usually around the 60%-65% mark, have risen to 90%-95%. However, migrants are afraid to move into some hotels, which are tainted by stories of unscrupulous owners failing to maintain basic hygiene standards in rooms and toilets. There is also an issue of overcrowding, with some hoteliers rumoured to be putting multiple occupants into one room.

Desperate times call for desperate measures, which these clearly are. The reality is that Germany was simply not prepared for such high volumes of migrants at a time when its housing stock was already coming under increasing pressure. Now the country faces a new challenge.

“Nobody knows how many migrants will decide to stay and integrate with German society,” says Matthias Pink, head of research at Savills Germany. “It’s also unclear where these migrants will be displaced and if other members of their families will join them. As a result, it is still quite difficult for the government to gauge the scale of the problem.”

What is clear is there are a growing number of people from war-torn countries such as Syria and Iraq who have risked everything to come to Germany, before making the difficult decision to journey home due to the poor conditions and the limited prospects for their future.

“I cried with happiness when we arrived here,” says Ahmed. “But now I have less than when I arrived here. If I had something before, now I have nothing left.”

In the airport departure hall, he shares his last packet of cookies with his three kids, while his exhausted wife falls asleep. When Ahmed’s flight to Baghdad is called, I ask him what he will do when he gets home. “We don’t know,” he admits. “We will take a bus to go near the Syrian border, but I don’t know if our house is still there.”

“Mum says we will die,” says one of the kids. Ahmed hugs him tightly. “We have nothing, but we will not die. I promise you this.”

No comments yet