In the heart of Belgravia, a large Georgian mansion sits empty. Cobwebs hang from the handles of the black front door, junk mail is crammed into the letterbox and dead plants lurk behind the windows, while a tired looking flag adorns the flagpole above the entrance.

The 19th-century building at 8 Belgrave Square is home to the Syrian Embassy (pictured above), closed since 2012 after the British government expelled all Syrian diplomats in protest at chemical weapon attacks on civilians during the country’s civil war.

No one knows if the Syrians will be back, yet its owner, The Grosvenor Estate, cannot do anything with the building because embassies are considered sovereign soil even if the freeholds are not owned by the country residing there.

As the US government shifts the embassy axis by moving out of Mayfair to Nine Elms, Property Week investigates who now owns all the diplomatic properties in the UK, using data from LandInsight. We also discover how landlords deal with problem tenants and ask if they are more trouble than they are worth.

The list of embassy owners makes for interesting reading. As well as familiar names such as The Crown Estate, The Grosvenor Estate, The Howard de Walden Estate, the Candy brothers and Hong Kong billionaire Samuel Tak Lee, it includes the president of the United Arab Emirates, a Ukrainian oligarch, an Iraqi military contractor and a Saudi sheikh.

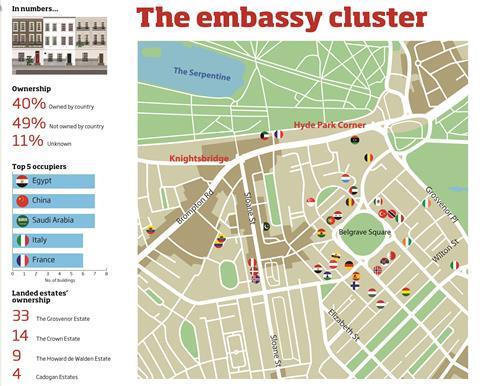

One of the reasons diplomatic properties have attracted such a diverse pool of investors is that the majority are clustered in the most expensive area of the capital: the West End. Hundreds of diplomatic flags fly in Mayfair, Belgravia, Knightsbridge and St James’s.

Belgrave Square and the area near Buckingham Palace has become a hub for embassies. The square sits within The Grosvenor Estate and takes its name from one of the many titles of the Duke of Westminster, Viscount Belgrave. To this day, the Duke’s estate is still the UK’s single largest landlord of diplomatic properties, owning the freehold of 33 addresses and with countries such as Germany, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the UAE as tenants.

“Before the First World War, these properties were single-dwelling homes,” says Nigel Hughes, estate surveyor at Grosvenor Britain & Ireland. “But after the war, it became difficult for those buildings to be used as houses, as the social climate changed. That’s when embassies became interested.”

Embassy heartland

The oldest diplomatic property in London is the embassy of Austria, which has been in Belgrave Square for more than 150 years. Most of the other embassies have sprung up since the Second World War. The US, for example, constructed its former embassy, on Grosvenor Square, in the 1950s.

Embassies are also “a firm fixture” of The Howard de Walden Estate, says executive property director Simon Baynham. The estate’s tenants include the embassies of China and Poland.

Hughes agrees that embassies are good tenants. “Generally speaking we find that embassies abide by the terms of their leases,” he says, pointing out that most are on ground rents. “They would have paid a premium at the time and then be on a peppercorn or very low rent basis.”

The likes of Grosvenor and Howard de Walden prefer tenants that occupy buildings in their entirety because most of the properties are listed, making them very difficult to alter or to break up into flats. “The question is what can you do with these wonderful, beautiful large buildings? They have an element of impracticality about them,” says Baynham.

But while landlords may be fond of embassy occupiers, many agents think the negatives of dealing with foreign countries outweigh the positives. The main issue is diplomatic immunity. As one senior agent puts it: “The problem with embassies is that you have absolutely no control. What can you do if they don’t pay? Declare war?”

There is always a risk that the occupier could “hide behind the Vienna Convention and not pay their rent”, concedes Baynham, citing the fact that the 1961 convention makes the premises of a diplomatic mission inviolable and states that it cannot be entered without permission. The host country is also barred from seizing the property.

This, however, never happens, says Hughes. “The only case where they do claim diplomatic immunity is on insurance,” he says, explaining that most countries claim relief from a terrorism premium on their insurance because the British state, under the Vienna Convention, is bound to secure their premises. “If they don’t abide by the leases we have to go to the Foreign Office and ask them to intervene on our behalf,” Hughes adds. “But that’s very, very rare.”

Hypothetical threat

The Howard de Walden Estate has had only one major dispute in the past 20 years, says Baynham, citing an instance when a lease came to an end. “The building was very dilapidated and we struggled to make a dilapidation claim,” he recalls. “In the end, we did get support from the Foreign Office and did reach a settlement. The Foreign Office will support landlords when embassies are deliberately flouting UK laws.”

Even if the law allows them to, few landlords would mount a legal challenge, says Verity Bonney, a senior associate with the real estate dispute resolution group at law firm Ashurst. “A landlord would be reluctant to embark on litigation against a sovereign state,” she says. “You might win, but if you can’t take action or claim any damages, it will be a Pyrrhic victory.”

In the Syrian embassy example, Grosvenor is unlikely to seek redress. “Unless a country would surrender their lease, we wouldn’t seek to forfeit. We would much rather resolve the problem than take it away from them,” says Hughes.

Issues like the one with the Syrian Embassy are rare. However, embassies can often create a headache for their owners and neighbours. In 2014, British comedian Mark Thomas held a women’s Barbie car race outside the Saudi embassy to protest against the country’s former ban on women drivers; Wikileaks founder Julian Assange’s six-year asylum in the Ecuadorian Embassy has attracted activists and a large police presence nearby; and armed police stand guard outside embassies such as Turkey’s and Egypt’s that are potential terrorist targets.

“Do you want to be next to a building with a policeman armed with a machine gun?” asks Baynham. “You’re unlikely to be burgled, but it’s not a welcoming feeling.”

Security was one of the factors behind the US government’s decision to move its embassy from Grosvenor Square to Nine Elms. Another factor was space. Foreign countries have been shrinking or expanding their diplomatic force.

Find out more - US Embassy relocation: was it a bad deal?

Canada moved out of Mayfair and consolidated its property at Canada House in Trafalgar Square in early 2015. This May, China purchased the iconic 5.4-acre Royal Mint Court site near the Tower of London to build a new embassy and office complex on a site previously designated for a £750m, 600,000 sq ft office scheme.

Three of the seven buildings China occupies are on The Howard de Walden Estate. While Baynham expects the country to “dispose of one or two buildings” in the future, he says that “it’s not on their agenda to sell those buildings” yet.

Countries are moving and building their own premises because they want modern office space. “They can’t create the space that they really need and want [in a listed building],” says Baynham, adding that they are looking for large plots of land to establish their new digs and are no longer wedded to the West End. “People today are much more relaxed about where they locate. The embassies are no different.”

In 2015, the Netherlands, based near Hyde Park, followed the US and acquired a plot of land in Nine Elms, creating a potential new diplomatic quarter there if others also relocate.

There is another incentive to move: the leaseholds are worth a fortune. Countries in financial turmoil such as Venezuela, which owns four properties in central locations, could liquidate their assets for hundreds of millions.

The US raised $1bn from the sale of its properties in Grosvenor Square, including its former embassy, which Qatari Diar is turning into a luxury hotel. Other former embassies, meanwhile, are being converted back to their original residential use by the likes of Russian steel oligarch Oleg Deripaska.

Unfortunately, there are no such plans for the Syrian Embassy, which could stand empty until its lease expires in 2033. It is not the only embassy that has vacated the former embassy heartland. With the US Embassy now making Nine Elms its home and the global political climate more volatile than ever, the axis is only set to shift further.

Who owns what… and where?

To find out who owns the 303 diplomatic properties registered to 186 different countries in the UK, Property Week cross referenced data provided by LandInsight with records from the Land Registry, Companies House and overseas territories’ registrars, court documents, planning applications and public resources.

Our research reveals that 40% of the freeholds are owned by the country that occupies them, nearly half are owned by someone else and 11% have no clear owner that could be identified.

The Grosvenor Estate is the single biggest freeholder, with 33 embassies. Her Majesty the Queen is second, with 14 embassies, including those of Israel, Sudan and Russia, which are managed by The Crown Estate.

Nine diplomatic properties are located in Marylebone’s Portland Place as part of The Howard de Walden Estate, while the 14-acre Langham estate in Fitzrovia boasts the Embassy of the Democratic Republic of Congo and the National Tourism Office of Greece among its tenants. The estate, originally belonging to the Earl of Oxford, is owned through an offshore vehicle, Mount Eden Land, by Samuel Tak Lee, who bought it for £75m in 1994.

A mile to the south, in St James’s, the diplomatic missions of Bermuda and the Cayman Islands at 6 Arlington Street are also owned by an offshore company. David Sullivan, the billionaire co-owner and chairman of West Ham United, bought the 18,000 sq ft office building, which is opposite The Ritz hotel, for £38m in an off-market deal in 2016.

Meanwhile, Cadogan Estates owns four properties and The Portman Estate three. The other owners revealed by our research are lesser known in property circles — and more controversial. As is often the case with central London real estate, many buildings are owned by companies registered offshore.

Not far from Portland Place, Winchester House, an office building on Old Marylebone Road, hosts the embassies of South Sudan and the Republic of Guinea, as well as the Cultural Attache of Oman. The block’s owner is Iraqi businessman Namir El Akabi, whose name appears in the Panama Papers. He bought it in 2006 for £32m.

Also named in the Panama Papers is one of the richest men on the planet. Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, president of the UAE and Emir of Abu Dhabi, joined the list of embassy owners in February when he bought the freehold of 3 Hans Crescent in Knightsbridge, which houses the Embassies of Ecuador and Colombia, for £100,000.

The vendor, an offshore company registered in the Netherlands Antilles, bought the freehold for £441,000 in 2009. The Sheikh already owned the leasehold of five flats within the red brick-building, for which he paid collectively £15m.

The same building, which for the past six years has been the shelter of WikiLeaks’ founder Julian Assange, was also home to the Defence Office of Spain. In 2014, a company belonging to Christian Candy’s CPC Group bought the former mission, converted it into a luxury five-bedroom flat and sold it to a family of Saudi investors the following year.

A fellow Saudi, Sheikh Fakieh, a 93-year old billionaire whose companies supply 40% of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s chicken products, is also an owner. In 2007, Fakieh bought the freehold of Cumberland House on Kensington High Street, home to the Trade Section of the Philippines.

Last but not least is Ukrainian steel magnate and billionaire Victor Pinchuk, who owns the freehold to the Grand Buildings at 1-3 Strand. The former site of London’s Grand Hotel is now home to South Korea’s Cultural Centre.

Interestingly, while many countries that have had a chequered diplomatic record own their properties, the Cultural Bureau of Saudi Arabia is owned by the London Diocesan Fund.

No comments yet