Launched in autumn 2012 by consultancy Central and law firm Mishcon de Reya, the Big Think on the Future of London hosted debates to address the needs of the capital’s increasingly flexible, connected workforce

Download the full print version >>>

Fortunately for London, throughout the sustained grip of the recession, its economy has been subtly rebalancing, helping to compensate for the downturn in financial services.

Creative industries have flourished. And through convergence with the software and telecoms sector, they are powering the city’s economic growth. The people employed in this young, dynamic sector have a very different relationship with the city: they commute by bike not company car; they have short-term contracts, rather than jobs for life, and their work spans both the real and virtual world. Measures of success are different — attributes such as flexibility and collaboration are core to success.

The scale of this sector, driven by these “new industrialists”, is amplifying a lifestyle shift in the capital — as it is in economic twin New York. Both cities now support a new way of urban living, and the rise of east London is a microcosm of this.

But even away from Old Street’s “Silicon Roundabout” in Shoreditch, things have changed. The drive to plan for the “human scale” is both enabling and responding to the way we live “more publicly”. London’s streets and public spaces are an extension of our living and dining rooms and working spaces, and are a big part of our culture.

We share experiences on social media, and we now share cars and bikes — and even our homes, through homestay sites such as Airbnb.

If the future is flexible, open, creative and collaborative, we must consider what that means for London’s policy-makers and developers. That is the essence of the Big Think.

Patricia Brown, director at Central, and Susan Freeman, property partner at Mishcon de Reya

London’s new networks

Cycling

Bicycles are an ever-increasing feature of London’s transport network — there are now twice as many cyclists in the city as in 2000. And census data show one in seven Hackney residents cycle to work.

Meanwhile, commuters want offices to provide bike-friendly facilities — 93% of respondents to a recent British Council for Offices survey reported demand for storage, showers and lockers had increased.

“Most think that providing high-quality facilities is not significant to rental values, suggesting the provision of cycling facilities is well on the way to being regarded as the norm,” says the survey.

Creativity

London’s creative sector is the second largest in the capital. Design, advertising, film, fashion, media and software, among other industries, contribute 16% of the city’s gross annual value added and are worth a collective £20bn, says the Greater London Authority.

Mayor of London Boris Johnson said in October this creative economy was “critical” to capital’s prosperity. Business leaders believe there are opportunities for cross-business fertilisation, and that access to capital, technological infrastructure and talented staff encouraged them to establish a base in the city.

Connectivity

Demand is increasing for fast and reliable wi-fi services to support smartphones and mobile data traffic across London.

In December 2012, the City of London corporation made the Square Mile an area for unlimited free wi-fi, after user numbers doubled during trials. The corporation stated that the district needed to keep pace with a “rapidly evolving technological landscape”.

Wi-fi is also being rolled out across the London Tube network, and smartphone technology is becoming smarter, allowing users to store all credit, store, gym cards and even keys — making the physical wallet redundant.

Generation ‘bleisure’

The growth of the virtual world means work can be done anywhere — the office can be accessed from a cafe, taxi or beach. It is a phenomenon called “bleisure” — a blurring of business and leisure time — and it is the modus operandi of a new generation of workers who have flexible attitudes to work, and technology to support it. Advertising company CBS Outdoor figures show this kind of work adds £9bn a year to the economy.

But London also hosts 414 serviced office centres for flexible workers — more than any other global city. Figures from office provider Instant show the capital’s serviced office market equates to that of New York, Paris, Hong Kong, Tokyo and Sydney combined.

Generation rent

Private-rented sector living has doubled in size over the last decade. One in four London households rent, across 850,000 homes in the capital. Government figures show that the rising cost of home ownership means the average London house price is five times the average London salary.

But rental costs are on the rise, too. A recent National Housing Federation study predicted that average rents in the capital will increase by 50% by 2020. A two-bedroom flat would therefore rise from £1,346 a month to more than £2,000.

Breathing spaces

As part of mayor of London Boris Johnson’s plans to improve the capital’s public realm, 2,000 street trees will be planted this spring — part of his aim to increase tree cover in the capital by 5% by 2025. It follows research in New York that shows every $1 spent on trees generates $5 in quantifiable benefits — from increased property prices and workplace productivity, to reduced energy consumption. The City of New York City Parks and Recreation department found its 600,000 street trees provide an annual benefit of $100m — more than five times what it cost to maintain them. Charity GreenSpace estimates that by providing opportunities for physical activity, London’s Regent’s Park saves the UK health budget £3m a year.

The Big Themes

From improving the private-rented sector to modernising high streets, Lucy Scott reviews issues raised in Big Think debates

London has always been a creature of change. Its shifting boundaries, transient population and economic strength mean trying to define what does or should make the city successful is not easy.

But the nature of change under way in the capital today means challenges are emerging that have never been seen before.

In fact, savvy policy-makers and developers are just as concerned with what collaborative economics or the proliferation of internet hotspots across the city mean for the built environment as they are with square footage and yield.

The Big Think on the Future of London is a series of debates that was launched last autumn by consultancy Central and law firm Mishcon de Reya, to discuss how the city can replicate its east London success story, how to tackle its housing crisis and what the capital’s public realm should be.

The starting point for all three debates was a recognition that London’s economic future now rests with an entirely new breed of business and worker.

The capital’s creative industries are an increasingly dominant part of its landscape and have been hailed by mayor Boris Johnson as “critical” to its success. And their influence is causing many to question whether the shape of the city and our approaches to its design now seem thoroughly anachronistic.

For these “new industrialists” — variously referred to as generation “bleisure”, generation rent and generation green — transport means bicycles, networking means social media and office space means the local cafe or spare bedroom. It is clear the built environment needs to catch up.

With this in mind, a range of panellists from the development, telecoms, design and public sectors came together to present their insights into ways to best harness the growth of new and creative industries for the greater economic good. The aim: to provide a thematic blueprint to dictate the policy and development agenda.

As Eric van der Kleij, special adviser on technology at Canary Wharf Group, said at the first debate: “We are all economically challenged and, as a city, we do need a new narrative.”

However that narrative emerges, having “vision” must be its central thread, it was argued. For those undertaking regeneration schemes in the capital, “vision” could in fact be nothing more complicated than allowing occupiers to determine the character of a place, or accommodating art or performance space in a vacant unit — as Cathedral Group did with the MVMNT cafe in Greenwich.

Robert Evans, partner of King’s Cross Central developer Argent points out: “As developers we shouldn’t be trying to fix things a decade out.

The people who use the space create the tone, and they have created a tone that is relaxed and fun — professional, not corporate.”

The Big Think uncovered stories of real change under way. On the pages that follow, we reveal the ideas and approaches shaping a new kind of London and catering for a new kind of Londoner. And we explore the themes the panellists believe must be embraced more fully, more often — by developers, planners and policy-makers — to

drive the changes the city so badly needs.

1. DEVELOPING PEOPLE-CENTRED PLACES

As our relationship with the city changes, both commercial and residential developers are responding by designing schemes around people’s need for a great ecology of place — in terms of its connectivity to surrounding areas and its immediate community.

Commercial developers need to understand “how the cutting edge is growing”, says Richard Upton, chief executive of Cathedral Group.

“It needs white-collar factories where minds can think, not air conditioning,” he says.

Upton believes people-centred places are vital. This, he says, involves knowing what coffee your tenants drink or whether they like to eat sushi.

It fosters long-term commitment to places and creates more accessible schemes that reflect the way life is lived. It is a philosophy the developer is embracing at the Old Vinyl Factory in Hayes, a 17 acre business park and former centre for the world’s vinyl production in west London.

Determined to bring a new approach to the “tired business park” format, Cathedral has introduced branded bicycles for staff to use to cycle into town in their lunch hour, a vibrant cafe space with 1,000 seven-inch singles spread across the walls, and a pedestrian walkway that connects the complex to Hayes town centre.

Richard Baldwin, Derwent London’s head of development, shares this mindset.

Derwent’s Tea Building on Shoreditch High Street was created from a block of early-20th-century warehouses. It was refurbished to create open spaces shaped by freshly painted old brick and pipework, allowing occupiers the freedom to make a unit their own.

But people-centred places connect with their immediate environment, too. Both Upton and Baldwin see the glass and steel boxes that separate workers from the outside as a thing of the past. Human spaces are about connectivity and bringing the “outside in” — providing space for occupiers, as well as access to flow in and out.

This principle can be seen in action at the Angel Building in Islington, where Derwent has opened up the reception so anyone can come in.

“Occupiers like to get out of their office and into other space within the building,” says Baldwin.

Big Think panellists argued that, in the residential sector, the city needs to cater to a range of needs, engendering diverse communities and allowing a variety of occupiers to engage with the built environment. As Amanda Reynolds, Hackney resident and director of masterplanning and design consultancy AR Urbanism, points out, London’s city centre housing must begin to cater to the “active elderly”, for example.

“There are people who are looking to come back into the [city] centre as their kids disappear. Others have been there for years and don’t want to go anywhere else. We need new types of housing — that is about the procurement process. Will banks lend on those sorts of properties? There are demographic challenges that must be grappled with.”

2. MASTERPLANNING FOR CHANGE

The story of Shoreditch’s rise to prominence was the starting point of the first Big Think debate.

The district’s success has been organic, but panellists were asked to consider whether that success could be planned and replicated.

Steve Edge, founder and creative director of branding business Edge Design, says the “Shoreditch factor” cannot be commoditised.

“When I moved to Shoreditch 30 years ago, there was nobody there. It was perfect for creative people because it had big spaces in old, beautiful buildings that were really cheap. It was edgy — and risky. That’s why Shoreditch is what it is now. No one planned for it to be that way.”

Any masterplan that tried to prescribe fringe activities would be making “huge mistakes”, believe panellists.

“I don’t remember anyone who set about to create an art cluster and pulled it off,” says Jason Prior, chief executive of planning, design and development for Aecom. “We need to back off on restrictions, and controlling [of] places.”

Argent is cited as an example of a developer that “takes risks to make places”.

“[Argent] isn’t prescriptive. At Brindleyplace [in Birmingham city centre] it gave people free rent to get their business off the ground. Developers need to harness the power of people,” says Prior.

Argent’s executive director, Robert Evans, who spoke during the debate about public realm, says successful masterplanning is about allowing uses and the nature of the place to emerge. Bringing a sense of life to King’s Cross, he says, was a “constant layering process” that changed with every new occupier.

King’s Cross has undoubtedly benefited from having a single developer with long-term vision. But panellists believe that, where districts have fragmented ownership, the public sector needs to engage with “iterative” masterplanning to shape the evolution of places.

“Policy shouldn’t over-engineer, but should balance individualism with a neighbourhood plan,” says Richard McCarthy, director at Capita Symonds. “Plan it, build it, maintain it. Have some controls about use. But give it space to change and iterate. Let people do things you didn’t think possible.”

3. AUTHENTICITY, CHARACTER AND DIVERSITY

As successful places gain in value, they inevitably lose the authenticity and diversity that made them attractive. Meanwhile, many businesses and residents are sifted out by rising rents.

This probably does not keep many developers awake at night. But the Big Think explored why it should, and concluded that streetscapes must be designed to respond to local — not homogenised — uses, if they are to maintain a sense of place. This consideration must influence public realm, too.

“How do you create a difference? So many places look cloned,” says Central director Patricia Brown, who chaired all three debates. “We need to look at how people are using space, make alterations and change what doesn’t work — but work with the sense of place that’s already there.”

New London industrialist Marc Blinder, director of European operations, business development and strategy at Adobe, says firms such as his need a working environment defined by more than the office they occupy.

Have some controls about use. But let people do things you didn’t think possible

Richard McCarthy, Capita Symonds

It can be as simple as having streets with an “ad hoc, authentic feel” that lacks globalised brands.

“We need and want to be near our clients, and near cool places so we can take them out.”

A sense of heritage and community is intrinsic to innovation, says David Randall, head of business and development for UK and Ireland at online residential accommodation marketplace Airbnb. His firm moved to Tech City in 2012 because of its ecology of start-ups and entrepreneurs.

“It has the type of people we wanted to grow our business with, and a social life around it, too.”

Capitalising on the spirit of edgy locations without killing it off can often mean turning down the tenants that raise revenue but foster cloned streetscapes. Many also see the artistic community as the foundation for retaining diversity.

Residential developer Londonewcastle is collaborating with the city’s creative community in this way by allowing artists to use its vacant spaces. Project Space, on the site of the Huntingdon Estate in Shoreditch, is a former printworks open to the whole community for events, galleries and installations (pictured, overleaf). And as part of the developer’s Street Art initiative, local artists can use as canvases buildings that are awaiting planning consent.

“The success of Hackney Wick was attracting artists that drove regeneration through art,” says Tom McGlynn, associate at David Kohn Architects. “That appeals to young professionals — and there’s your consumer base. In Peckham the art scene has driven regeneration and there is a complete mix — an African church, a theatre and bars. It’s that kind of density that makes places successful.”

4. HARNESSING CREATIVITY FOR GROWTH

Recognising the link between creative industries and economic growth was at the heart of the Big Think debates.

Panellists believe the city needs to better nurture fledgling businesses for the greater good. As well as creating the right workspace and sustainable transport opportunities to attract talent, growth can be encouraged by providing better technical support.

Investing in technology to help workers to make best use of buildings and tackle to-do lists on the move is paramount, say panellists.

Peckham’s art scene has driven regeneration — that kind of density makes a place successful

Tom McGlynn, David Kohn Architects

“[Economic growth] will come from whole industries and firms we don’t yet know of. So we need to ensure there are opportunities for interaction. This means making the infrastructure and connectivity world class,” says Mark Kleinman, assistant director of economic and business policy at the Greater London Authority.

“In some cases, it can be so difficult to upgrade the internet system of a building, it is easier and cheaper for occupiers to move elsewhere,” says Central’s Brown.

But risk-taking is also needed to attract creative business. Canary Wharf Group’s Eric van der Kleij says developers need to take more risks with young businesses that do not have triple A covenants.

A case in point is Instagram, the free photo-sharing platform and social network bought by Facebook in September for $1bn — just two years after its launch.

“If you were approached by Instagram in its first year [for a lease] and they had no accounts, but a great idea, how would you see it?” asks Van der Kleij. “That’s the kind of business we have to think differently about — and embrace. We need to be more active and aware as landlords.”

5. GOOD-QUALITY RENTED HOMES FOR LONDONERS

There has been much public debate around whether the future housing market will focus on homeowners or renters — not to mention how banks resolve funding issues to improve supply in both markets. But as the second Big Think debate revealed, generation rent is more concerned with the quality of places they occupy, rather than whose name is on the deed.

Leaky windows, poorly managed properties and peeling paint are the realities for so many Londoners living in buy-to-let homes.

“London once worried about having no key worker properties, but now it isn’t just key workers, it is anyone on a normal income,” says Elliot Lipton, executive director of Triathlon Homes. “We need supply, fullstop.”

As the average rent for a two-bedroom property is set to increase to £2,000 a month by 2020, panellists felt raising standards in rented homes was imperative to retain young workers as they move up the career ladder.

Ecology of place was a theme touched on throughout, and was considered vital to raising the quality of residential schemes. Homes and amenities should, it was concluded, cater to a range of demographic groups and ages.

The debate heard how the London Borough of Ealing has worked with housebuilder Berkeley on a scheme of affordable housing for existing council tenants over 55 years old to tackle the under-occupation of family-sized homes, releasing the properties back into the market.

Pat Hayes, executive director of regeneration and housing for the council, told panellists the housing association had 400 people who wanted to sign up: “They don’t necessarily want a big family home, but to be near amenities that allow them an active retirement. We would definitely look at doing a similar product again.”

But panellists also believe brownfield land should be made available to help to hit housing targets, while developers could create large build-to-rent schemes in London’s outer suburbs.

As McCarthy says: “It is clear that large-scale institutional development will be difficult to achieve. I am sure transport infrastructure such as Crossrail has been underestimated in terms of its ability to increase land values.”

6. MAKING RENTAL COOL AND DESIRABLE

Developing rental models that work for both landlords and tenants is considered a key aspect in the evolution of London’s rental market.

Panellists believe longer-term leases, a greater sense of community, control over one’s home and better management should form the basis of a newly professionalised private-rented sector model.

At new rental scheme East Village, the former Olympic athletes’ village, Delancey is trying to tap into increasing demand from the city’s well-heeled young professionals.

It aims to professionalise a range of services that it believes tenants will be prepared to pay for, and plans to retain on-site tenant management and longer-term contacts.

Panellists also believe developers need to make renting cool by offering facilities that cater to modern urban lifestyles — access to green space, allotments, free gym access and the opportunity to make a rented place a home.

Fashioning a brand with which generation rent can identify is an approach Fizzy Living has taken to market its private-rented schemes in Epsom and Canning Town. It has created a fun brand that uses Twitter to help with asset management and communication. Crucially, it has designed its flats for renters, with equal-sized bedrooms that have their own storage and bathroom facilities, and large communal spaces.

7. GOOD DESIGN ENABLES HIGH-DENSITY LIVING

Over in Milan, a skyscraper that hosts the world’s first vertical forest is nearly complete. The Bosco Verticale, will house 900 trees across 9,000 sq metres of terrace created by Stefano Boeri and has been designed as a solution to the city’s

space shortage and dire need for greenery.

Schemes such as this prove higher-density living does not have to be uncomfortable. And as living more densely seems likely to be the most sustainable form of development, London must also make neighbourhoods more palatable with good design and innovation.

The debates therefore explored ways in which higher-density schemes could improve quality of life. More compact living space must be balanced with the addition of well-designed amenities such as bicycle parks and shared laundry facilities, say panellists.

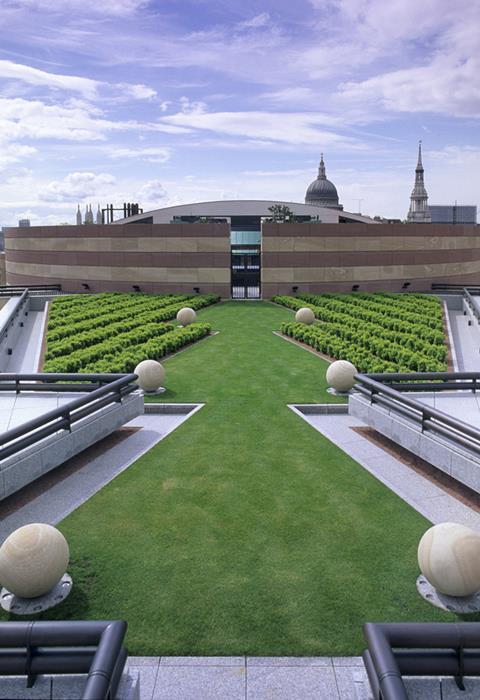

Public space also has a role to play in allowing residents access to natural space. In recognition of that, green walls and roofs are becoming part of London’s landscape. And Transport for London has installed greenery at St James’s Tube station, West Ham bus garage and Edgware Road. In the City, buildings such as 1 Poultry and 201 Bishopsgate now feature green roofs.

8. SPACE AND MOVEMENT IN PUBLIC REALM

Defining what great public realm is and needs to be was a central concern for the Big Think, particularly as people are now “living more publicly”. London, it was suggested, needs more spaces such as the courtyard of Somerset House — where a car park has been transformed into a thriving cultural space used by children, ice skaters and artists.

Tot Brill, assistant chief executive for 2012 and special projects for the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, explains: “We are moving away from the separation between public and private. In the 1950s, pubs had closed doors and everything happened inside. Now, people spill on to the pavement. There is a sea-change in public living. Our job is to mediate that.”

The Big Think addressed how public space could be better designed to support new ways of working, socialising and moving around the city — as well as honour its core desire for greater ecology of place.

At root, great public space manifests by “letting space change and iterate” — as McCarthy says, “letting people do things you didn’t think were possible”. And embracing overlooked spaces to inject life into the gaps of central and suburban neighbourhoods is key.

The empty railway yard or derelict car park could become a communal place for education or socialising. London has several such examples — including Southwark’s Union Street Urban Orchard, an active public space that flourished at the hands of local volunteers and artists on a disused site in summer 2010.

“People are always searching for things that are credible and authentic,” says Argent’s Evans. “And people other than the developer are better able to bring that to a place.”

But connectivity was also a theme. Streets and squares should be designed around “connectivity and permeability”.

“Great space is about use and movement,” says Tim Stonor, managing director of Space Syntax.

This is being put into practice in Hackney, where recreational and green space has been created to improve quality of life. The council is gradually introducing 20 mph speed limits.

As a result, one in seven Hackney residents now cycles to work.

Perhaps the “in-between” places are a good starting point. Richard Powell, Capco’s director of planning and development for Earls Court, says its masterplan began by focusing on the “gaps between buildings and the public realm”. The developer is currently considering how to revitalise the area around North End Road.

“If we can get to a position where the local community believe this is part of the environment in which they live, that is success for us,” concludes Powell.

The changing face of London business

David Randall

Head of business and development for UK and Ireland at online residential accommodation marketplace Airbnb

“The type of people we wanted to grow our business with lived in Hackney. We love the social world around there, too. We have had great experiences getting to know other start-ups.

“We are about people sharing homes with others and travelling. People are now willing to let strangers they don’t know to come and stay in their room. That represents a huge cultural shift.

“Visits to our Hackney and Camden properties are our fastest growing. Tonight there will be 1,200 people staying in our properties. People want to go to places like this because they don’t want to be near the traditional tourism industry. They want local experiences — to hang out in the bar that’s always been there.”

Rahul Ahuja

Former investment banker who now runs collaborative consumption start-up Taskhub

“Collaborative consumption is not going to go away — multi-billion-dollar companies are coming out of this trend.

“For the soft launch of Taskhub, we partnered with large telecoms companies and looked at GPS of phones to see where we should roll out first based on that data. So that idea could be used to create better public realm, too.

“I don’t think we need much more space, but we need to make better use of what we have.

“But better space does not have to be altruistic. I’m not driven by wanting a cheaper deal, but by wanting better experiences.”

New York talent hunt

New York and London’s economies rise and fall in parallel, and both have focused on rebalancing the economy in the recession. Like London, the Big Apple has found its salvation in its growing tech ecosystem.

New York’s new tech industrialists are forging business districts away from the traditional central business district, driven by interesting space and a cluster of other signifiers, such as galleries and bars. In particular, Brooklyn’s Dumbo, Redhook and Williamsburg districts and Lower Manhattan’s Broadway corridor have spawned the moniker “Silicon Alley”.

Tech geek mayor Michael Bloomberg quickly identified this trend as a game-changer for New York. He has channelled hundreds of millions of city dollars to accelerate this fledgling sector’s growth and has even hosted “Tech Meetups”.

An applied sciences and engineering campus — the result of the city’s international competition and $200m of investment — is under construction on Roosevelt Island. Designed to future-proof skills, it is leveraging $1bn of private capital and will create an estimated 600 companies and 30,000 jobs.

It is two years from being completed, but the first “Cornell NYC Tech” students nonetheless began a one-year masters degree in January on a temporary campus space donated by Google.

Talent is the biggest asset of a knowledge economy and retaining it is essential for New York’s economic future. Although its urban intensity still works for some, people increasingly seek urban buzz with a softer centre — clean air, walking or cycling down tree-lined streets to a local park or plaza, to watch the world go by, work, or play with the kids. This has prompted the city’s audacious roll out of pedestrian plazas, family-friendly streets, bike lanes and bike share schemes, and riverside and neighbourhood parks. And it aims to plant 1 million trees in the next 10 years.

A younger, creative population, breathing fresh life into tired neighbourhoods, has helped to drive change in New York. Yet the Bloomberg administration has spotted the desire of many — young and old, rich and poor — to live differently. The door will close on Bloomberg’s term of office at the end of 2013, leaving New York a changed place.

Patricia Brown, director, Central

High street for the 21st century

Capital & Counties’ Earls Court redevelopment presents a rare opportunity to create a new, fit-for-purpose high street. With endless debate around the survival of the high street, developers have the chance to think differently when starting with a blank canvas. The single ownership of this 77 acre site is key, as fragmentation prevents a cohesive strategy.

The new high street will connect the two boroughs of Kensington and Chelsea and Hammersmith and Fulham, and the new village centres of Earls Court and North End.

Gary Yardley, investment director at Capco, says: “Our aspiration is that it will be a social hub, somewhere for residents to use and for others to choose to visit and hang out.”

Each section must stand alone and have its own personality. Yardley says the overarching concern is how to make it a great place to live.

This important thoroughfare will house a series of activities, including one-off shops, galleries and experiential offers. Food will be important but a huge supermarket is not planned, as there is a 24-hour Tesco just north of the site. As Richard Powell, Capco’s director of planning and development for Earls Court, said at the public realm debate,”retail is likely to be less than 50% of the new high street”.

Expanding on the vision, he says: “We don’t see it as full retail. There will be cultural uses, school access, health and community centres.”

Masterplanner Sir Terry Farrell stresses the importance of management of the spaces between the buildings that will be used for markets, festivals and other activities.

Yardley cites Marylebone High Street as an exemplar of a successful high street. Like Earls Court in single ownership, it is carefully managed, has a good mix of uses and a school and food market behind it.

But, says Yardley: “Its weakness is its traffic flow, which, if planning again at design stage, you may do differently.” At Earls Court, careful thought will be given to how buses, cars, cyclists and pedestrians use the new high street. Priority will be given to walkers and cyclists to extend dwell times.

“We don’t see it as a busy traffic street but it won’t be pedestrianised,” says Powell. There will be different residential products in the overall Earls Court scheme, and the high street will suit those who choose to live in a busier environment.

The design will be carefully fine tuned. Pavements facing the sun will be over-emphasised, and wide pavements and open shop fronts will create a lively, energetic street. The location of shade-giving trees will also be considered. The importance of being able to plan this is apparent when looking at the east end of Oxford Street, which cries out for wider pavements.

Perhaps we are overly concerned about the future of the high street.

As Farrell points out: “High streets have always reinvented themselves and they must have adaptability and flexibility to allow for change.”

Susan Freeman, property partner, Mishcon de Reya

London’s landscape

Schemes that changed the scene

Trafalgar Square, 1800s

The vision of architect John Nash established the foundations of this open public cultural space. It has also been used as a centre of national democracy and protest.

South Bank, 1900s

The Festival of Britain in 1951 helped to redefine the riverside location as a place for arts and entertainment. Today, it is a thriving mixed-used district that hosts street art, musicians and tourists.

Somerset House, 2000s

The space that was previously a car park is now home to an arts and cultural centre, and hosts 55 water fountains in the summer months.

The Big Think, a Central concept, has been produced in partnership with Mishcon de Reya and media partner Property Week. Central and Mishcon would like to thank sponsors Capita Symonds, Derwent London, James Andrew Residential and Londonewcastle, and everyone who contributed to the round table debates.

No comments yet