One of the big downsides of Brexit, we were warned in the run-up to the EU referendum, was the potential loss of jobs from London, particularly from the banking and financial sectors.

Those fears seemed to be realised in the aftermath of the vote, with the most extreme forecasts predicting up to 100,000 jobs would go.

The main beneficiaries of this Brexit brain drain were expected to be Paris, Dublin and, first, the German cities of Frankfurt and Berlin.

The week after the vote, one UK agent told Property Week they had already heard the German markets were looking to capitalise, with Frankfurt eyeing the financial sectors and Berlin the fintech and proptech sectors.

Yet on a two-day visit to the two German cities, Property Week found agents were only cautiously optimistic. So has the attraction of such markets over London been overstated? And what changes do agents expect to see in Frankfurt and Berlin?

After touching down at Frankfurt’s impressive airport on the early flight from London Heathrow, I took just 20 minutes to get to the city’s Bankenviertel (banking district) by taxi. The business day was just getting started and the majority of people milling around on the streets were middle-aged men in suits.

The scene isn’t a million miles removed from the City early in the morning, but the City it is not. The impressive-looking skyscrapers belie the fact that Frankfurt is a city still licking its wounds from the financial crisis.

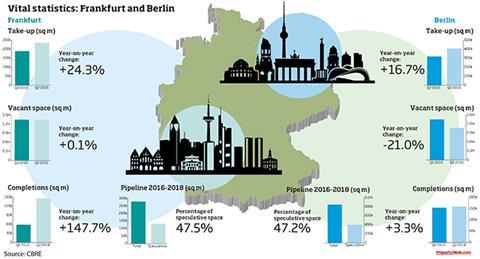

Harder hit than most global cities because of its reliance on the financial sector, it has not yet fully recovered, as attested by its office vacancy rate of almost 12% compared with 6.2% in the City of London.

Watchful approach in Frankfurt

CBRE’s managing director and head of agency for Germany, Carsten Ape, is certainly not as gung-ho as some about its prospects, preferring to adopt a wait-and-see approach until there is more clarity on job movements.

“We should be very cautious about the Brexit hype,” he says. “There are a lot of people talking about it, and I’m sure it will be positive for Frankfurt, but this will be in the long run. We need to be careful that we don’t overestimate the whole situation.”

Ape’s restraint is understandable. Demand levels have not recovered since 2008. While on the one hand, the high vacancy rate suggests there is space to move into, the reality is that supply is constrained, with total stock standing at just 11.5m sq m (124m sq ft). That issue is only likely to intensify.

There is a lack of construction activity in the Central Banking District (CBD). Where London’s skyline is punctuated by dozens of cranes, there are barely a handful in Frankfurt. In fact, there are just three office schemes in the pipeline.

The largest is Tishman Speyer’s Omniturn scheme, which will total 41,530 sq m of office space when completed in 2019. The WinX tower will bring another 35,000 sq m of space to the market in 2018, while the third scheme, Marienturm, will see 11,600 sq m built by 2019.

In total, around 200,000 sq m of new office space will be brought to the market by 2020. That could actually turn out to be good timing with negotiations for Brexit expected to take up to four years.

Early discussions

However, a large percentage of the new stock has been pre-let, and four years is a long time. If people want to move their staff before 2020, there is currently about 200,000 sq m of space available in the CBD. In short, the choices are fairly limited.

It is not just the office space that is a concern. “The availability of residential could be critical; the offer is very limited,” notes Ape, a view echoed by Colliers partner and office letting agent for Frankfurt, Stephan Bräuning.

He believes that the limitations in the residential market could be a deciding factor in banking firms moving employees out of London. “The main problem is there is nowhere to live,” he says. “If most employees come to Frankfurt, then we have problems. It will put a huge pressure on the residential market.”

Bräuning does, however, expect some of the 360,000 employees in the London financial sector to move to Frankfurt. He says the likes of Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley are already having early discussions with their landlords about reserving the vacant space in their current building in case they need to take it.

“If 10% of employees from the banking and financial sector in London were to move to Frankfurt, all the vacant space would be gone,” he says. “We won’t get every employee moving from London, but we will get our share. A lot of companies are already here so it wouldn’t be a complete new set-up but a case of just relocating people.”

Deutsche Bank has said it could move up to 8,000 staff to Frankfurt. In space terms, that would require around 160,000 sq m of space, given that occupiers allocate 20 sq m to every employee in Germany.

This, however, also presents problems for Frankfurt. “There is not one building that could take even a quarter of that space,” Bräuning states. “It depends on how fast they need to move. If the process is for the next three to four years, then the new developments will be up by then, but if it’s for the next 12 to 18 months there is not enough space available.”

Frankfurt is not only competing with the likes of Paris and Dublin for banking jobs migrating from London. It is also competing with London itself. “I doubt the senior banking guys will be willing to move from an international city like London to a village like Frankfurt,” says JLL’s team leader for office leasing in Frankfurt, Christian Lanfer.

It is a feeling that is shared by Dr Jan Linsin, CBRE’s head of research for Germany. “We are realistic that Frankfurt isn’t London,” he says.

“London is the most prominent and most dynamic market in the world. It is the financial centre - it was before the Brexit vote and will continue to be after Brexit.”

Berlin boom time?

But what of Berlin? While London has always had the upper hand in the financial community over Frankfurt and many believe it will continue to, the rivalry between Berlin and London for the crown of tech start-up capital of Europe is far more intense.

Since the vote, Berlin has made no bones of the fact that it thinks it can overtake London. The German liberal political party FDP even sent a mobile billboard to the streets of London in the days after the vote proclaiming: “Dear start-ups, keep calm and move to Berlin.”

The attractions are many. For one, the city is top of the heap in Europe when it comes to venture capital investment.

EY research shows venture capital invested in Berlin exceeded $2.3bn (£1.8bn) last year compared with $1.9bn in London and that investment is growing faster in the city than in London.

If money starts to dry up in London in the wake of the EU referendum vote, start-ups will have to think about alternative locations, says Alexander Ubach-Utermöhl, founder of Blackprint Partners, which is trying to attract proptech firms from London to his accelerator programme. Berlin makes perfect sense as a choice, he says.

“Before the vote, it was clear that British start-ups were better off based in the UK with easy access to funds and where the culture is more open to tech,” he says in a bustling, uber-cool café in the Rosenthaler Platz area of the city.

“Since Brexit… my feeling is this will change. They will follow the money and in the last two years there has been more venture capital money in Berlin than in London.”

CBRE’s Nicolás Mercker-Sagué, who specialises in the tech sector in Berlin, agrees. He says the sector accounted for 30% of office take-up in the first six months of this year, and is well placed to benefit from any Brexit fallout. “London was a no-brainer in terms of location for tech firms and co-working operators,” he says. “Perhaps now we will have a better situation.”

Development woes across Germany

However, as in Frankfurt, there are challenges - particularly when it comes to delivering the sort of space tech start-ups want, namely co-working and serviced office space.

Although Berlin’s vacancy rate stands at just 6% and it recorded its strongest first half-year take-up performance since records began this year at 407,500 sq m, the development pipeline is lagging behind.

It is particularly hard for co-working operators to get hold of new space. Cushman & Wakefield’s head of office agency in Berlin, Heiko Himme, says that by the time new developments are completed, they are largely fully let as supply of high-end space is scarce, leaving tech firms with a small pool to choose from and scratching around for older existing stock.

“If co-working space is to be developed, it will have to be in redeveloped warehouse buildings,” he adds. “There is huge demand for co-working space but it is pretty much fully occupied.”

Berliners are also worried about the wider implication of the Brexit vote, which could act as a drag-anchor on the German - and EU - economy. “It’s too early to be euphoric or bullish,” says Matthias Hauff, head of agency in Berlin at CBRE.

“We could all be the loser. There is a high risk that in the end all of us will have the [same] problem.”

That is not the only imponderable, of course. Even if the UK is the only nation to leave Europe and does so in a relatively orderly fashion, the agents in Germany are right to be only cautiously optimistic that they will benefit.

In Frankfurt, there is a huge problem not just with a lack of office supply but also with a lack of quality residential space.

And in Berlin, Brexit or no Brexit, there is not enough of any sort of office space, let alone the co-working space tech start-ups demand.

In short, many people could be relocated to Germany. The question is where to put them… and would they want to go?

No comments yet