Just how dirty is offshore money?

|

David Cameron threw the proverbial cat among the pigeons in July when, with a steely glare at the UK property industry, he warned that the UK must not become “a safe haven for corrupt money from around the world” and that “there is no place for dirty money in Britain”. While the prime minister was wrong to insinuate that all offshore money is dirty, he was right to raise the red flag. As the National Crime Agency (NCA) report he cited shows, criminals are using offshore territories and the anonymity many provide to launder dirty money through UK property, particularly in the high-end residential market. The (multi)billion dollar question is how much? To date, most attempts to answer this question have been based on a limited cut of the NCA and Land Registry data. Now, however, Property Week has analysed the full dataset for the first time. Here we reveal the true extent of offshore money flowing into England and Wales – detailing where it is going to and where it is coming from. We also ask: just how dirty is this money and what exactly should be done about it? |

|

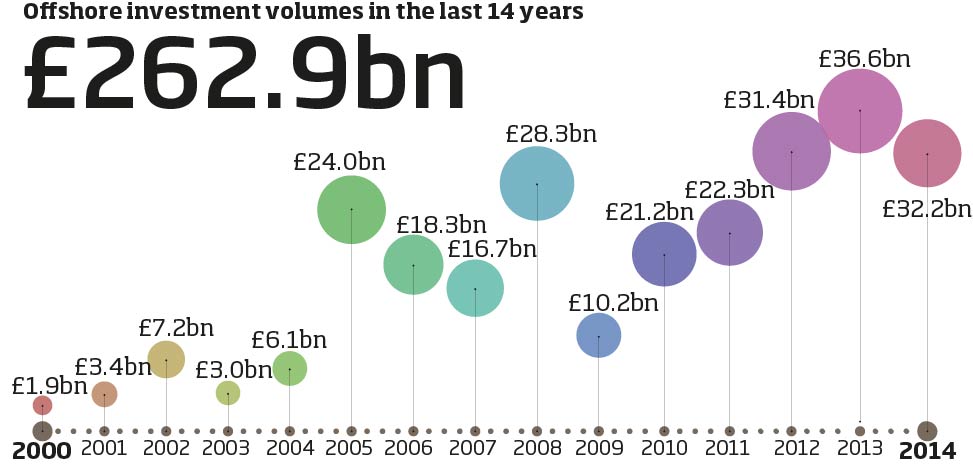

Unknown scaleAlarmingly, the NCA has no idea of the true scale of the problem, unsurprisingly given the nature of the people involved. But while the amount of dirty money coming into the UK property industry is hard to establish, what can be assessed is the amount of money coming in from offshore companies – and from that, the potential scale at least. The NCA report was based on a Land Registry database of property in England and Wales owned by offshore companies. This database was released in August, but attracted remarkably little attention other than in satirical stalwart Private Eye and, significantly, that only crunched part of the data; Property Week has crunched the entire dataset and the results do not paint a pretty picture. Suffice to say, if the rise in money laundering correlates even vaguely with the rise in spend by offshore companies, we have a very serious problem to contend with – and one that is on a much larger scale than we had previously realised. In the first definitive analysis of the data, we can reveal that a whopping £263bn worth of commercial and residential property has been acquired in England and Wales by offshore companies since 2000. What’s more, the value of property acquired each year has increased exponentially, from just shy of £2bn in 2000 to a staggering £37bn in 2013 – an increase of more than 18-fold – although last year saw a slight fall to £32bn, probably as a result of the political uncertainty in the build-up to May’s election. It will come as no surprise that London dominates, accounting for £143bn or 54% of the total. The South East is the next most popular destination (£31bn), followed by the North West (£22bn) and East of England (£15bn). Of course, the fact investment in property in England and Wales has been made by companies incorporated abroad does not in itself mean the money is dirty. Jurisdictions such as Sweden, Denmark and the US feature in the list of countries the money is coming from – nations boasting incorporation rules similar to our own that are regarded as fairly robust in deterring criminal activity. It may seem surprising that countries such as the US, China or Russia do not feature higher up the list. However, it needs to be remembered that the ranking is based on money spent on property by offshore companies, not companies registered in their own domestic markets. In other words, the £2bn spent by offshore companies registered in the US on property in England and Wales does not include acquisitions made directly by, say, a New York fund. What it does include is money spent on property in England and Wales by those that have registered their companies offshore in the US. And, as the data shows all too clearly, the amount of money being spent by offshore companies has risen far more than anyone realised. It has become common practice for a foreign company or individual to set up offshore vehicles to make their overseas investments as tax efficient as possible. Again, it is important to stress that not all of those areas should be tarred with the same brush in terms of the secrecy involved in their governance arrangements. For instance, topping our ranking is Jersey – a tax haven for sure, but low risk from an anti-corruption point of view. On the British mainland, all registered companies are required to state their beneficial owner – the individual or individuals that profit from the firm – on a public record. In Jersey, that record isn’t publicly available, but it is maintained and can be accessed by law enforcement officers and others with demonstrable need. Most of the UK ‘Know Your Client’ (KYC) and due-diligence requirements also apply on the island. |

MethodologyThe findings in this report are based on a dataset collated by the Land Registry. In order to compile the datatset, the Land Registry ran a search of its records to identify transactions where the purchaser was an offshore company. For the Land Registry's purposes, "overseas company" includes companies in the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man. The Land Registry has been maintaining an inventory of offshore companies in the register since January 1999. However, the data for 1999 was incomplete, so for the purposes of clarity, our analysis relates only to the years 2000-14. Land Registry data does not differentiate between residential and commercial property. |

Hiding in the sunAs a result, Jersey is the go-to destination for individuals and companies seeking to acquire UK property in a tax-efficient manner. In total, nearly £85bn (32%) of the money spent by companies incorporated abroad came from Jersey. Given the territory combines tax efficiency with a decent degree of transparency that should come as no surprise. “We work with a number of investors in Asia,” says one City lawyer. “And whenever they ask us where are the preferred jurisdictions, we always say that if they want to have the flexibility of trading the assets, their best choice is Jersey because it’s a jurisdiction that most institutions are comfortable with.” The same cannot be said for the British Virgin Islands (BVI) – and it is here that things start to get murky. Again, it would be wrong to imply that everyone registering their business on the islands is corrupt. But the regime is so lacking in transparency, it would be equally wrong to understate how vulnerable to exploitation it is by those who are. The islands provide near-complete confidentiality in terms of the identity of the beneficial owners of companies incorporated there. Even stating the purposes of a company is optional. According to the World Bank, offshore companies can be created in the BVI in less than 48 hours from anywhere in the world, they can cost as little as $1,000 to register and on occasion they can even be registered without the individuals having to formally identify themselves. This would be less of an issue if the islands only accounted for a small amount of the acquisitions made by offshore firms. But according to our analysis, companies registered in the BVI make up nearly 20% of the total foreign registered company money spent on property in the UK as a whole since 2000 – and 26% of the total in London. Indeed, such is the perceived risk associated with the jurisdiction that some institutions – particularly listed propcos – are deeply uncomfortable about doing business with a company registered in the jurisdiction. “If someone looking to invest chooses somewhere like the BVI for their investment vehicle, then for some institutions that could mean they will want a heavier burden of due diligence before they can transact with that vehicle or in some cases, they may not be able to transact at all,” says Leona Ahmed, real estate division managing partner at Addleshaw Goddard. “A BVI entity will have their internal risk and compliance people on a higher alert than normal. Rightly or wrongly some jurisdictions are perceived as having greater risks attached to them. The problem is that, as the NCA admits, the opaque nature of such regimes makes it virtually impossible to establish how much of the money coming from them is corrupt. “A combination of factors mean that we will never know exactly how much criminal money is being laundered through the UK market,” a spokesman admits. “These factors include the hidden nature of the problem, the intermingling of legitimate and illegitimate funds and the lack of transparency in some source countries.” The spokesman adds in 2013/14, the NCA received 354,186 reports from regulated professionals and that the sheer number coupled with its limited resources means it “cannot investigate each and every one”. The lack of transparency or understanding of the scale of the problem should not, however, be seen as an invitation to the property industry to turn a blind eye. Rather the reverse, says Steven Jack, JLL’s UK head of risk and compliance. “My point of view is if the prime minister is moved to comment on this, it suggests this is an issue the industry must address,” he says. “Although I’ve seen real commitment from our board and staff to do the right thing, and the same from most other firms, there remain firms or agents who will cut corners.” Indeed, property agents are singled out as a weak link in the anti-money laundering (AML) chain by both the NCA and non-governmental organisation Transparency International (TI). The NCA’s National Assessment of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing highlighted concerns over the level of reporting from the estate agency sector, while a report released by TI in February raised similar concerns. Suspicious activities reports (SARs) to the NCA from agents – a legal requirement for most professionals in regulated sectors – lag behind other parts of the industry. The NCA spokesman says: “SARs from the estate agency sector... lack clarity as to the reason for reporting, indicating a general lack of understanding of the requirement and purpose of the regime.” What’s more, according the NCA’s 2013-14 report on SARs, agents contributed just 0.05% (179) of all SARs submitted in that year. According to TI: “Quite clearly, this figure is not commensurate to the risks posed by money launderers to the UK property market.” To be fair, there is the world of difference between large and small agents. Complying with AML regulations is a time-consuming and expensive process, but for understandable reasons the law does not discriminate between a global behemoth like JLL or a single-office, high-street residential agent. A key requirement on all regulated professionals acting in a property deal in the UK is that they know who their end client is – the so-called beneficial owner, who may be many offshore entities removed from the representative seeking to make the transaction. The exception is when an agent (note not a lawyer, banker or accountant) is acting on behalf of a buyer, although JLL and CBRE say they do due diligence on both sides of a transaction. “The regulatory requirement... is on the vendor,” confirms a spokesman for CBRE. “However, we do undertake checks on our purchasers.” In law, KYC regulations are supposed to mean that if you can’t identify the beneficial owner in a deal, you should walk away. That is simply not happening all the time. “If they have any reason for suspicion, professionals are required to try to identify the beneficial owner under enhanced due diligence,” says Nick Maxwell, head of advocacy and research at TI and a former anti-money laundering adviser to NATO. “But because offshore secrecy is such a prevalent part of the economy, on a regular basis these checks are not being carried out and the beneficial owner isn’t being discovered.” |

Offshore spend by administrative county |

Into the lightThe big property advisers generally have compliance departments similar, albeit on a smaller scale, to those found in major banks, accountancy and law firms. However, smaller agents may be ignorant of the regulations. Speaking to TI earlier this year, National Association of Estate Agents’ managing director Mark Hayward stated: “When agency staff see something suspicious, it would be common for them not to know that they should report it or understand how. Training and awareness need to be improved.” Quite apart from the size of the agents involved, it is also the case that the potential for dodgy deals is higher in the residential sphere. Commercial deals involving millions of pounds generally involve major banks, accountancy and law firms, and agents, all of which have established compliance departments and international reputations to lose. Conversely, the purchase of a £2m flat in Kensington is likely to involve a high-street agent and a small conveyancing firm. “You’ll be using a residential conveyancer and they can vary,” says the City lawyer. “It could be a one-man band above a kebab shop on Balham high street. They’re still bound by the same regulations, but if you’re looking for a soft option you’d choose a firm that doesn’t have the manpower to do this stuff or the resources to hire someone to do it on their behalf.” So what’s to be done? TI has an elegant proposal: legislate to make it a requirement on all property deals that the beneficial owner is known before title deeds can be transferred. The change would at a stroke apply to purchasers based anywhere in the world. “It’s a good way to boost transparency without having to legislate over different jurisdictions,” says Maxwell. “It’s the most effective action the UK government could take.” Some may argue that there are valid reasons for investors to keep their interests private, but under TI’s proposal there is no need for beneficial owners’ details to be made public: they just need to be available to the authorities if required. Property Week asked leading surveying firms whether they would support further tightening of AML regulations in the UK and whether this could damage investment in UK property. The answer that came back from JLL’s Jack should reassure the NCA that parts of the property industry, at least, are keen to play their part in preventing criminality. “The most important change we need to tackle this issue is in the laws governing transparency of ownership,” says Jack. “By making ownership more transparent, we will make it more difficult for criminals to launder money through UK property. We can keep the regulations principles-based and in force through constructive oversight and audit.” What’s more, Jack says that it should be possible to toughen up regulations without damaging UK property’s international reputation as an attractive investment option. “It is possible for action to happen unilaterally,” he says. “Tackling this issue creates more security for legitimate investment and builds the UK’s case as a global hub for property.” As it happens, the government is expected to publish a consultation imminently on further changes to AML regulations. While Maxwell doesn’t want to pre-empt the consultation, he is hopeful TI’s proposal will feature, especially given Cameron’s speech in Singapore. “It’s good to see the government acting to commit to a consultation on greater transparency of foreign holding of property,” he says. Whether the proposal would enjoy the widespread support of the property industry is a different matter. But if the huge increase in money being spent by offshore companies indicates that money laundering too is on the increase, it is clear something substantial needs to be done. |

Offshore spend by region |

The UK property industry benefits hugely from inward investment from all corners of the globe. But that investment is both a blessing and a curse. David Cameron has claimed UK properties “are being bought by people overseas through anonymous shell companies, some with plundered or laundered cash”. Is he right?

The UK property industry benefits hugely from inward investment from all corners of the globe. But that investment is both a blessing and a curse. David Cameron has claimed UK properties “are being bought by people overseas through anonymous shell companies, some with plundered or laundered cash”. Is he right?