It was a cold morning in February last year and Elena Pavlova was watching TV at her home in east Moscow. She had been living in her modest flat since 1967, when she was 10 years old. Outside her window, the kids from a local kindergarten were playing in the snow.

On TV, the mayor of Moscow, Sergey Sobyanin, was talking to Vladimir Putin in a public debate. Elena wasn’t paying much attention to what the two were saying until Sobyanin said he intended to start an ambitious programme to demolish every khrushchevka in the Russian capital.

Elena froze. “I was so scared I didn’t know what to do, so I stayed still,” she told me.

Her flat is in a khrushchevka, one of the austere, five-storey Soviet blocks that surround the capital. Others think they are an eyesore, but Elena loves her flat. In springtime, the lime trees around it blossom with beautiful flowers. Her home is in the Izmaylovo district, which she would later learn is at the top of Sobyanin’s ‘renovation’ list. She is one of the 1.6 million people affected by the programme who will be forced to relocate if her home is demolished.

The demolition of the khrushchevkas is a highly controversial and sensitive issue in Moscow. Some people support it, saying the dilapidated estates must be knocked down to make space for more modern and comfortable buildings. Others strongly oppose the demolition, arguing that most blocks are solidly built and could last for years.

The debate is expected to intensify as Russia heads to the presidential elections next week, and the Moscow municipal elections next year. A fortnight ago, Property Week visited the minus-20°C city to find out about the pros and cons of one of the largest regeneration programmes in the world.

Khrushchevkas take their name from Nikita Khrushchev, the former Soviet leader during whose rule the blocks were built, between the mid-1950s and 1960s. When Joseph Stalin died, in 1953, Khrushchev inherited the worst housing crisis of the 20th century. Around three million Muscovites living in cramped old communal estates with shared bathrooms, toilets and kitchens were in dire need of shelter.

“After the war, people just needed a roof over their head,” says Alexandra Sinilova, residential development director at Savills in Russia. “Some khrushchevkas were built in four months using prefabricated panels and were not meant to last. Others were of better quality, like the ones made of so-called ‘Stalin’s stones’, thick and large concrete bricks.” The prefabricated khrushchevkas, which Sinilova calls “economy class”, were commonly known as ‘khrushchebi’, a pun for “Khrushchev’s slums”.

It is not the first time khrushchevkas have been demolished. Sobyanin’s predecessor, Yuri Luzhkov, launched a similar programme in 1996, which involved the demolition of 1,772 buildings and took more than 20 years to complete – the last building under the Luzhkov programme came down last month.

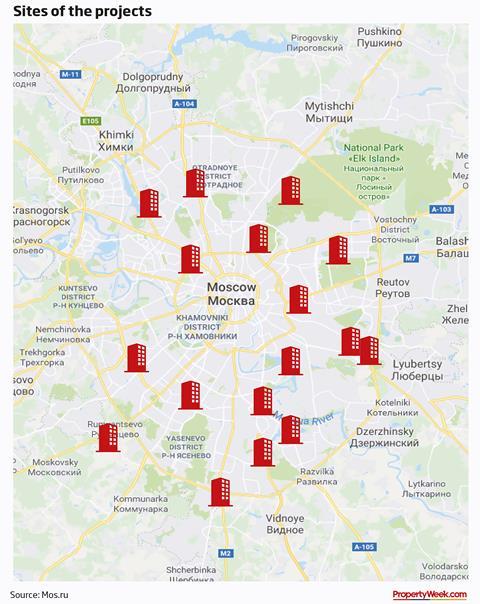

With a cost estimated between 3.5trn rubles (£40bn) and 6trn rubles (£76bn), Sobyanin’s ‘Moscow renovation project’ is huge even by inflated Russian standards. It originally involved around 8,500 buildings, accounting for more than 250m sq ft, or almost 20% of the entire housing stock in the capital. After facing stern opposition, the number was reduced to 4,500 – then it was raised again, to 5,143.

Street protests

The mayor hoped his flagship programme would be warmly greeted by Muscovites. He was wrong. Soon after the TV debate, several hundred thousand people took to the streets to protest against the ‘renovation’ programme. It was one of the largest popular movements in Moscow since the fall of the Soviet Union. Putin’s reply to Sobyanin’s announcement was that he needed to handle his plan “in a way that makes people happy”.

Some people were clearly not happy. Elena was one of them. After her initial paralysis, she knocked on every door in her block, telling her neighbours what Sobyanin wanted to do with their homes.

When Valentina Amelkina heard the screams outside her door she thought it was the police, but it was Elena, her neighbour. Valentina didn’t watch the debate (her grandson told her not to trust state TV) so she was taken by surprise. In the beginning, she was scared too.

She has lived in her flat since 1965, when she and her husband moved in as newlyweds. After the collapse of the USSR, in 1991, residents of the khrushchevkas were allowed to buy their flats. It was the first time in their lives that they could buy any form of private property.

Khrushchevkas are not suitable for modern life. They have no elevator or modern heating

Alexandra Sinilova, Savills

Valentina is 81 and lives with her widowed daughter, who is 60. She tells me that she has recently changed her mind about the relocation: “It doesn’t make a difference where I live. I’m old. But my grandchildren and grand-grandchildren can inherit a new home.”

She says she wanted to refurbish her flat anyhow. Before the TV debate, she even sent a letter to Sobyanin asking him to pay for the renovations (the mayor did not respond). Her roof leaks but she doesn’t know if she should fix it.

“Khrushchevkas are not suitable for modern life,” says Savills’ Sinilova. “They have no elevator, no modern heating. Moscow has always been a city for comfortable living and now it needs a new makeover.”

Her grandparents live in a khrushchevka, too. Sinilova says the kitchen is so small that it can fit just one person – but five live in the flat. “It’s so much easier and way more convenient to demolish instead of refurbish them.”

Regeneration project

Savills and other estate agents say the renovation programme would also have a positive impact on the country’s stagnant construction industry. Since the Russian economic crisis took hold in 2014, the sector has been hit by falling oil prices, the depreciation of the ruble and western sanctions. The project would be a shot in the arm for housebuilders.

Irina Ushakova, head of capital markets at CBRE Russia, says that such a huge development opportunity will “change the mentality” of residential developers. “The project is now targeting about 17% of the existing housing stock in Moscow. It’s quite significant in terms of the market turnaround. I’m not sure we have ever seen such an impact in one time.”

One of Sobyanin’s most important decisions as a mayor was to ban any commercial development within the capital’s third ring, roughly corresponding to the M25 in London. CBRE says only 2% of the khrushchevkas are within that area, so developers would be able to build retail and leisure alongside the new blocks.

The project is now targeting about 17% of the existing housing stock in Moscow

Irina Ushakova, CBRE Russia

Despite being mainly residential, the regeneration project would need to be supported by some commercial real estate, says Tim Millard, head of advisory at JLL Russia. “It’s the Moscow standard,” he says. “There is no equivalent of our section 106, but the rule is that for every two living units you have to build one workspace.”

The Duma (city government) has created a state-controlled ‘renovation fund’ to oversee the project. Although a final budget has not yet been approved, the city has already allocated 400bn rubles (£4.1bn) for a preliminary phase.

State-driven programme

“Depending on the locations, there will be some form of subcontracting to private developers,” says Ushakova, but it’s not clear how consistent this will be. “This is specifically a centrally controlled programme,” she adds. “For example, I wouldn’t expect any of the large agents to be directly involved in the masterplan or to have an advisory role.”

CBRE reckons the project could take more than 20 years, although it is officially scheduled for completion in 2032. “It’s a long process,” says Ushakova. “First you have to build something new to move people out of the old blocks. Then you can demolish them and build something in their place.”

Valentina is not sure she will live to see her new flat. Elena tells her not to worry. “Don’t be silly,” she tells her. “You’ll live another 20 years in this flat!” She reminds her that her grandmother was 102 when she died. “Yes, my babushka moved with us in this building,” Valentina says. “She died peacefully in her bed, right in this room. Things were different back then.”

Like Elena, Kari Guggenberger is one of the many Moscow residents who were angered by Sobyanin’s announcement of the khrushchevka demolition programme that February morning. She watched the debate on YouTube and as soon as she realised what was going on, she threatened the mayor on Twitter. “I will bury you!” she tweeted, echoing Khrushchev’s words to western ambassadors during the Cold War.

Kari, a 36-year-old IT company manager, lives with her nine cats in a khrushchevka in the Savelovsky area, about 15km north west of Elena’s district. She was among the co-ordinators of the first protest rallies against Sobyanin’s plan and is administrator of the Facebook group ‘Muscovites against demolition’, which has racked up more than 27,000 subscribers.

Kari used to live on the 12th floor of a new high-rise block in a fancy area of Moscow, but soon realised she couldn’t stand it.

“There were no trees around there, too much traffic and too many people, because of the high density that they’ve created overnight,” she says. “There were queues for everything, from shops to ATMs. By midweek, there were no fruit and vegetables left at the supermarket.”

Preliminary plans released by the mayor’s cabinet show that the new blocks are expected to be both taller and larger than the existing five-storey khrushchevkas. Some of the schemes built by the previous mayor have between 30 and 35 floors. Residents claim that any supporting infrastructure would not be enough to mitigate the impact of such high-rise buildings on small neighbourhoods.

“The flats themselves might get larger, but people will be living in more condensed areas,” CBRE’s Ushakova concedes. “The big question is if the quality will match people’s expectations.”

Elena, Kari and the other residents who attended the protests in May do not believe it will. They are also afraid they will be relocated far away from their jobs, schools and relatives. The authorities have issued contradictory statements regarding relocations. It’s not clear if people will be moved “within the same area” – as indicated by Sobyanin’s renovation bill – or the same district.

‘Location’ is the main reason that led Kari, who still owns the apartment downtown, to move into a khrushchevka near her birthplace. “Now I have three parks around me,” she says. “There are no cars and I know all my neighbours. I’ve even convinced my mum to move nearby.”

She has lived here since 2010. The apartment looks brand new and is decorated in numerous different shades of pink. Kari, who wears a green top and matching green nail polish, tells me the money she has spent refurbishing her flat is more or less the same amount she paid to buy it (several million rubles).

Kari has become a symbol of the protests against the khrushchevka demolitions. “It’s because I look like a blonde bimbo and I have a strange German name,” she says with a laugh. “I’d never been to a rally before. I was a Barbie!”

Despite her lack of experience as a protester, Kari and her fellow activists have managed to get more than 500 khrushchevkas taken off the demolition list. Now the residents of around another 200 buildings are asking for their help.

“Each building counts,” says Kari, who adds that if the protesters manage to save even a few buildings in one neighbourhood, the developers won’t be able to assemble the land they need and might have to cancel their plans.

Corruption claims

Under a law approved by the Russian parliament in August, a khrushchevka cannot be slated for demolition if less than two thirds of its residents agree to be relocated, but the activists claim the polls have been rigged in many districts and accuse the authorities of using false signatures.

Accusations of corruption have dogged the renovation programme since its announcement. Ilya Shumanov, deputy director of Transparency International Russia, says the programme is the perfect example of how “Putin’s state capitalism works nowadays”. He adds that the real beneficiaries of the renovation will be developers close to the Kremlin.

“The government is paying government-owned companies to do one of the largest redevelopment projects in the history of Moscow,” he says. “They’re simply taking money from one pocket to put it into another one.”

Shumanov adds that while a law to prevent such conflicts of interest was introduced in 1995, it was not implemented, “which has allowed construction clans to run free”.

We are deliberately kept in the dark. Nobody knows what’s going on

Kari Guggenberger, protester

JLL’s Millard acknowledges the concerns: “The residential sector has improved under Sobyanin, but is still not transparent. It’s not the place for a multinational firm like ours.”

It is rumoured that the bulldozers will start to rumble after the election, although the city’s vice mayor recently said the renovations might not take off until next year. “We are deliberately kept in the dark,” says Kari. “Nobody knows what’s going on. They don’t want us to know.”

The battle for the khrushchevkas won’t stop after the elections. Indeed, it is likely to get worse. However, Kari and the other ‘Muscovites against demolition’ have a solution that they hope will suit everyone: a plan for people who want to stay in a khrushchevka to swap places with residents in blocks not due for demolition, but who are willing to relocate. They are consulting local deputies and collecting signatures to propose it to the Duma.

Kari hopes the plan will work. “Some people wouldn’t be able to live in the very same khrushchevka, but at least they would have their small buildings and leafy neighbourhoods.”

That is Elena Pavlova’s hope too. Since that first TV debate, she hasn’t stopped fighting. She’s not scared anymore and she says she won’t give up until her khrushchevka – and the others around it – are safe. “I can’t surrender now. My lime trees will blossom in June.”

And she would like to see them from the window of her flat.

Source

1 Readers' comment