Few films are as tied to a location as Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, which recently celebrated its 50th anniversary.

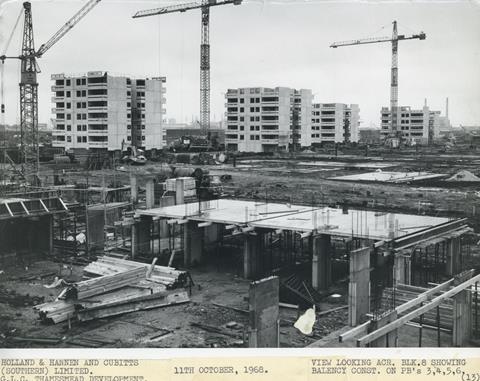

For his adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s novel about a society overrun by gratuitous violence and tap-dancing ‘Droogs’, the visionary director needed somewhere that looked both futuristic and godless. The recently completed brutalist South Thamesmead housing estate in south-east London, with its imposing grey concrete tower blocks, fit the bill.

“The brutalist look was just perfect for him,” says Alison Castle, a film historian and author of TASCHEN coffee-table books including The Stanley Kubrick Archives.

“Filming on location was not logistically complicated and because such architecture was still so unfamiliar to the public, they could really believe it was futuristic,” adds Castle. “Kubrick’s choice of Thamesmead showed a very prescient instinct for how this architecture was deeply misguided and even hostile, doomed to fail as a model for living. As modernist as the buildings were, I believe he saw in them a dystopia.”

Castle describes the film as “a masterpiece” and references the iconic sequence where Alex DeLarge (played by Malcolm McDowell) attacks a member of his own gang, kicking him into Thamesmead’s ground-level marina in rhythm to the overture of Rossini’s The Thieving Magpie.

“That scene does an excellent job of calling attention to the central ‘lake’ feature of the housing complex, which is so artificial-looking it sums up the entire failed logic behind such social architecture projects,” says Castle.

Historic failure

The Thamesmead project, with its utopian ideals for a ‘town of tomorrow’ yet ultimately poor transport links (it was not included in the Jubilee line extension) and weak local economy, is today regarded as an historic failure.

Cut off from the north of the Thames and sandwiched between the Blackwall and Dartford tunnels, the south-east London estate quickly became isolated in the years after its opening in the late 1960s. Its low density meant it was rarely buzzing either, and the complex labyrinth of overhead walkways connecting the blocks made residents feel claustrophobic and fearful of being followed.

The idea of A Clockwork Orange was more powerful back then than now

Rowan Moore, Observer

The wide roads below – designed for a car-based future – were not the most enticing places to hang around. Promises of jobs and better transport links failed to materialise. According to the BBC, several councils used it as a “sink estate”, a place to rehome their so-called “problem families”. The BBC also reported stories of locals vandalising buildings and “families who felt trapped”.

Whatever the root of the project’s decline (and there are many theories), it became a juicy story for journalists to contrast the area’s poor fortunes with a controversial film that Kubrick himself – in the wake of public outcry after copycat crimes were linked by tabloids to A Clockwork Orange’s graphic depictions of murder and social disorder – had pulled from general release in 1973. Ironically, this decision made film fans even more eager to track down an illicit copy.

In his book Militant Modernism, writer Owen Hatherley claims that Thamesmead was “associated with the physical brutality” of the Droog gang’s orgy of nihilism. It meant that whenever a violent crime was reported from the area in the 1970s, 1980s or even 1990s, many people would picture thugs belting out Singin’ in the Rain while beating up homeless people in dimly lit alleyways.

But over the years that image has faded. “The idea of A Clockwork Orange was more powerful back then than it is now,” says Rowan Moore, The Observer’s architecture critic. He has reported extensively on the estate’s fortunes since London housing association Peabody took up the reins in 2014, triggering a massive regeneration plan for the town – the Thamesmead area measures around 760ha and Peabody owns around 65% of the land.

“I’m not sure people looking for affordable and safe housing care too much about a 50-year-old Kubrick movie,” says Moore. “Just look at the word ‘brutalist’. It was once an automatically negative connotation, but now there are books celebrating it in the Tate and concrete is seen as cool again.

“I think with the Thamesmead project there’s a big opportunity to say something along the lines of: ‘So this was the nightmare world of Kubrick, but just look at it now – it’s great!’ Also, the artistic prestige of being linked with a Kubrick movie will be cool in the eyes of a lot of potential homebuyers, especially hipsters.”

The Thamesmead I drive up to visit today looks very different to the dystopian pop culture legend. Given a tour of the site on a wet weekday morning by John Lewis, Peabody’s executive director for Thamesmead, and Adriana Marques, head of cultural strategy for Thamesmead, I am impressed by how they have built on the town’s brutalist bones (Peabody claims it will remove only one third of the original architecture) and just how green everything is, given its concrete massing.

“Our big USP here is just the scale of the greenery and the lakes,” says Marques, who previously worked on the Olympic Park project. “I think it’s twice the amount of open green space per resident that you get anywhere else in London. We have five lakes connected by this man-made network and picturesque canal. It means you have the brutalist towers at one end, then you walk for 10 minutes and see weeping willows and cygnets.”

Waterside transformation

Peabody has invested £2.5m in Southmere Lake, improving the water quality and creating a new wetlands area and fish-free channel to attract new wildlife and boost biodivesity.

The Thamesmead Waterfront 50:50 joint venture between Peabody and Lendlease plans to transform the waterside area into a compelling new location packed with restaurants, shops, festivals and community events.

It is all about positioning Thamesmead as a place of rediscovery

Adriana Marques, Peabody

Peabody has also repaired hundreds of existing buildings across the estate, replacing broken windows and tackling mould damage. Although it is planning to build thousands of new homes as part of the wider regeneration of the Thamesmead area, it is looking to do everything it can to enrich the lives of existing tenants, with the opening of a new community centre coming at a time when a lot of councils are shutting theirs down.

Meanwhile, the Lakeside Centre – which is located just a few hundred yards from where A Clockwork Orange’s iconic slow-motion waterside fight scene took place – is a fitting shade of orange and has been transformed into an arts and café space for locals.

Lewis says he is confident that “positive” negotiations to bring the Docklands Light Railway (DLR) to Thamesmead will soon be concluded.

“Having the DLR here would release the ability for us to deliver something up to 15,000 new homes and a whole new town centre,” he says. “We’re lucky to have inherited a large commercial portfolio. It’s about 1.6m sq ft of commercial space, which means we can grow the employment base for locals. With London rents so expensive, it makes sense for business to come to Thamesmead.”

A key objective for Lewis, who previously led the Milton Keynes regeneration project, is to restore local pride in the area. He argues that the housing association’s management of the area will mean it is less held up by red tape and is able to actually deliver on its promises.

“We want to give people here a sense of purpose, belonging and a safe home. It really felt like the area needed someone to come in and take the lead,” he says.

“The fact it’s divided by two different boroughs meant there was [previously] never a collective management. Quite often when you have government-led initiatives, the estates can be at the whim of changes to policy or funding lines.

“If you have someone like Peabody, we can guarantee consistency to make this a great place to live. We recognise it will take a long time, but we’re here for the long term.”

Cultural rebrand

The connotations of the word ‘Thamesmead’ have noticeably improved over recent years. There is now an annual Thamesmead Festival, which celebrates local artists and hosts one-off events. It has been included as part of the Greenwich+Docklands International Festival programme, which resulted in five secret candle-lit outdoor showings of Dennis Potter’s 1979 TV play Blue Remembered Hills, a Second World War film shot in Thamesmead.

There is also an annual culture fund that awards up to £2,000 towards cultural or community projects that directly benefit local residents. The slogan ‘Made In Thamesmead’ is repeated several times during my visit, reflecting the repositioning of the area.

“We’ve worked with Wayne Hemingway on branding and I think it is all about positioning Thamesmead as a place of culture but also rediscovery,” says Marques. “So one kind of phrase that we landed on was: ‘Think you know Thamesmead? Think again.’

“People talk about A Clockwork Orange being shot here, but so was Beautiful Thing, which is a pivotal and beautiful moment for LGBT cinema. We want to put plaques on the building like they did for My Beautiful Laundrette.”

If all the plans for the area come off, it sounds as though there could be a risk of gentrification, a suggestion Peabody quickly shoots down.

“There is always a risk of that with these redevelopments,” says Moore. “They [developers] tend to have good intentions and then the numbers get tight. People find they have to sell more market housing to balance the books or make the profits they wanted to make.”

Filmmaking heritage

Although Peabody is looking to the future, there is also an opportunity for Thamesmead to reclaim its historic links to A Clockwork Orange.

Marques says she contacted the Kubrick Estate about working on a project to celebrate the links and show the juxtaposition between the Thamesmead of the early 1970s and that of today.

“We went to the Kubrick Archives and it’s a bit of a closed door sadly,” she says. “For the Thamesmead 50th anniversary in 2018, we started a community archive. It was a semi-independent project that took more of a positive nod to the filmmaking heritage of the area.”

This heritage includes TV shows like Misfits as well as music videos by artists including A$AP Rocky, Skepta and Aphex Twin.

It’s about restoring pride. If we do that, then that’s a success

John Lewis, Peabody

But the Kubrick Estate’s decision to back away probably has more to do with the fact the making of the film was a disturbing experience for Kubrick, which garnered a lot of negative publicity.

“We know that the news of copycat crimes disturbed him immensely,” says Castle. “My suspicion is that Kubrick might have even questioned some of his artistic choices, such as the high stylisation of the costumes and sets.

“What’s ironic is that although A Clockwork Orange’s themes are as relevant as ever, today’s audiences are so inured to hardcore violence in films and video games that the scenes meant to provoke don’t feel all that provocative anymore. The film was simply ahead of its time, and people weren’t ready for it.”

Marques has one particular bugbear about Thamesmead’s ties to the dystopian classic, which was released on 18 January 1972 in the UK. “It always gets overlooked, but Kubrick filmed here in 1971, which means Thamesmead was just two years into development and a lot of the residents were not here yet,” she says.

“From speaking to the Kubrick Estate, I have learned he liked Thamesmead primarily for practical reasons – it was empty. There was nobody who was going to bug him about parking or lighting at night or filming hours. It looked dystopian because no one was living here. It is very different because we have 45,000 people living here now. By 2050, that will be more than 100,000. They’re very different places.”

Lewis says working on transforming the reputation of Milton Keynes is an experience that will help with his work on Thamesmead. “In Milton Keynes, your first headline is about concrete cows and then it becomes a concrete city. But you then say to the journalist: ‘Well, when were you last there?’

“And they say: ‘Oh I’ve never been, I’ve just read some of the sort of history.’ I think that’s when you can get a bit hooked into storytelling as opposed to reality.”

Lewis believes Thamesmead will eventually, through regeneration, shake off the negativity of the past, some of which was due to its connection to Kubrick’s film.

“I think the challenges for Thamesmead have been far more about inconsistent management of the place, the fact that some of the maintenance of buildings wasn’t strong enough, the fact that when lighting broke no one replaced it,” he concludes.

“So if people were a bit nervous about walking around, it wasn’t because of a Kubrick film; it was because they were really walking on dark streets that weren’t being looked after. That’s what we’ve sought to address and for us, it’s about executing the really boring things like cleaning the streets more regularly, emptying the bins, getting the lighting working, cutting the grass more frequently.

“It’s about restoring pride. If we do that, then that’s a success. Wouldn’t it be great just to say ‘I live in Thamesmead’ and for someone to say ‘oh, lovely!’”

To misquote chief Droog Alex, then the area will have been cured, all right.

No comments yet