The International WELL Building Institute recently announced it was forming a task force to consider ways of reducing the health burden from Covid-19 and other respiratory infections.

It’s a worthwhile initiative, but we need to think more deeply before rushing back into the workplace. A new workplace report by Colliers in the Netherlands suggests that 60% of office space may not be suitable for the immediate post-Covid period.

The introduction of the WELL standard to the office market in Europe five years ago has been a breath of fresh air (literally) for workplace design, and prioritising mental and physical wellbeing suddenly seems logical.

But working from home (WFH), sitting by the open window, I am certain that my physical environment is healthier than that typically provided by workspace buildings. Despite the efforts of WELL, we have a long way to go to learn how we can provide healthy indoor settings under normal circumstances, let alone if we are meant to design buildings that deal better with conquering infectious agents.

Meanwhile, the environmental impact of mass WFH on our city centres cannot be ignored. Air quality in cities has improved greatly during the Covid-19 crisis, with important implications. Stanford University scientists estimate that in China, reductions in emissions since the pandemic started have saved the lives of at least 1,400 children under five and 51,700 adults over 70.

We need a place to go and meet people and we need spaces in which to hide

We are also learning a lot about behaviour from our WFH experiment besides the development of new digital tools. Many people I’ve talked to say WFH is better for concentrated tasks. Modern workspace often lacks places of peace and quiet.

Although the Zoom meeting works quite well, it is planned and organised, so an important factor leading to new ideas is missing: the chance encounter. Interaction is a key ingredient of creativity, empathy, improbable insights and true innovation, and in a post-AI workplace we will need room to focus on the human qualities of workers. We need a place to go to and meet people, a social hub, and we need spaces in which to hide and concentrate.

In the Netherlands, where many of my projects are located, the focus of the real estate coronavirus discussion is firmly on the next period. New models are often accompanied by new terms; luckily, the Dutch language allows words to be cobbled together to make new ones.

The talk is now about the ‘anderhalvemetereconomie’: the economic reality of a society with a prescribed minimum distance between people of 1.5m.

Triggered by that is the need for the ‘anderhalvemeterkantoor’: the office that supports this distancing policy. This will mean 60% of desk spaces cannot be used, and according to a Colliers report, this constitutes a lack of workspace for 1.2 million people nationwide.

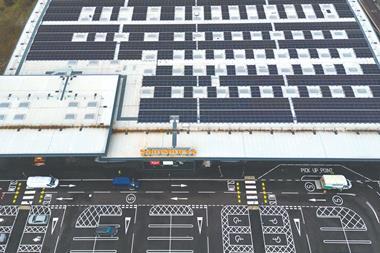

So how do we develop a more sustainable way forward for our built environment? Rather than quickly building more offices, it would make sense to continue WFH for a while longer and use the available office space as social work hubs. This will cut carbon emissions by reducing transport and reliance on new construction, while increasing the quality of urban environments and the health of inhabitants.

Ron Bakker is founding partner of PLP Architecture

No comments yet