Last week I chaired a Property Week half-day conference as part of our Climate Crisis Challenge campaign, held in a suitably sustainable venue: The Office Group’s recently completed Black & White Building in London’s fashionable Shoreditch.

The six-storey building, purpose-built as flexible office space, has garnered plenty of publicity for its ambitious use of timber. Designed by Waugh Thistleton Architects, it relies on two types of 21st-century plywood: laminated-veneer lumber (LVL) for the building’s rigid frame, plus cross-laminated timber (CLT) for the floors and core.

The facade also employs treated timber slats to control solar heating with plain, uncoated glazing – apparently the fancy films and coatings typically used with glazed facades turn the panes of glass into recycling rejects.

The pristine new building wears its credentials on its sleeve. The timber is proudly on show everywhere; serried planks of wood form the ceiling, framed by exposed heating and ventilation ducts, while the many layers of the laminate lumber are visible in the chunky pillars and beams. As a space, it feels inviting and vaguely nautical.

Architect Andrew Waugh gave delegates an entertaining account of the building’s conception and construction, aided by an unexpectedly jumbled slide show that meant nobody – Waugh included – knew exactly which part of the complex process he’d be describing next.

Waugh is a passionate advocate who sees no limit to the potential of timber, from taller buildings to retrofit extensions and improvements. He says laminated wood can be both lighter and stronger than concrete and steel, is cost-competitive and is light-years ahead in sustainability.

Not everyone is on board. Insurers are sceptical, with worries about water ingress. Waugh said The Black & White Building’s underwriters, worried about leaking pipes, insisted on old-fashioned joists and plywood for the bathroom floors. The combination might be structurally inferior to CLT, but brought the benefit of well-understood risks and simpler repairs.

Other speakers at our summit felt mass timber still enjoyed only niche appeal. Residential development is out, post-Grenfell, but some of the other niches where wood might gain traction could be surprising.

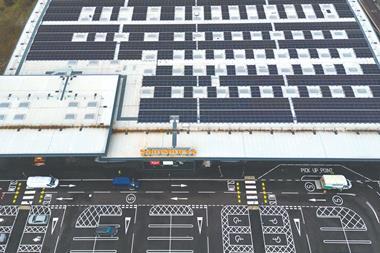

As outlined in our Industrial & Logistics supplement this week, Cromwell Property Group is piloting the use of structural wood in logistics buildings in northern Italy, close to Austria’s commercial forests. It is keeping concrete for columns but using timber for the huge roofs and facades of new warehouses. The developer concedes construction costs are higher, to secure contractors with the right skills.

David Hopkins, managing director of the Timber Trade Federation, last year told PW’s sister publication Construction News poor building practices were another significant barrier: “We have a bad habit in construction of trying to cut corners. Other materials are more forgiving, but timber can’t get wet; you can’t miss out fire-safety design; you have to be rigid [in your discipline]. There has to be a focus on quality, sustainability and safety, and a lot of the construction industry struggles with that concept.”

In stark contrast with most building approaches, timber construction has the potential to deliver lower than net zero carbon. Adopting wood more widely will be tricky, but as an industry we must grasp that potential, and learn how best to use it.

No comments yet