How would we cope if 16 million refugees arrived on Britain’s shores?

That’s the challenge Lebanon is facing, as the country now harbours more than a million Syrian refugees - around a quarter of its population. Syria and the horrors of its civil war are only around 40 miles away from Beirut - roughly the distance from central London to Reading - and understandably Lebanon’s capital is creaking under the strain.

As we report this week, the regional strife has also had a huge impact on the Beirut market: investment has dried up, a glut of flats sit unsold, and many developments are now on hold. But amid the gloom there are also signs of optimism and the city’s real estate sector is proving to be remarkably resilient.

It is, in some ways, a similar story in Rio de Janeiro, which we also visit for this week’s issue. Brazil is struggling with instability of its own: a political scandal, an economy in recession and a debt crisis. But Rio’s market is holding up surprisingly well, helped, at least in part, by the legacy of last year’s World Cup and the ongoing preparations for next year’s Olympic Games.

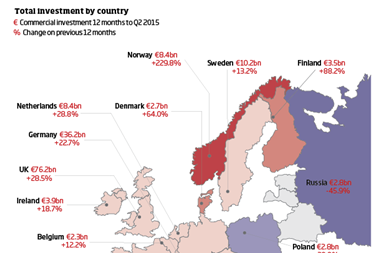

Back in Europe, the grip of the eurozone crisis has eased, but, despite the Greek debt deal, it has not entirely gone away and economic growth remains anaemic. Nevertheless, investors’ confidence in property continues to go from strength to strength, with European investment volumes expected to hit the highest level this year since the 2007 peak.

Three very different cases of global instability, but in each real estate is fairing better than one might expect: in an uncertain world, bricks and mortar are still clearly seen as a safe home for money.

Corbyn’s safe haven

One man who knows much about safe havens is Jeremy Corbyn. After all, the new Labour leader has spent his 32 years in parliament as MP for Islington North, the safest of safe Labour seats (and my constituency). As a result, Corbyn has had little or no experience of reaching out beyond the political divide, convincing those of a different political persuasion of his views.

He will have to do so if Labour is to cut through to voters. But there was little sign of that in Brighton this week, where the Labour party’s conference resembled something of a political safe haven, with a party retreating into its comfort zone and refusing to confront its election defeat.

But there may be one issue on which Corbyn can get some traction: the housing crisis. This week, Labour announced yet another review of housing policy, and two of Corbyn’s policy commitments - council housebuilding and rent controls - are already popular with voters.

It may be tempting to write Labour off, but if the party wins a hearing on housing the Conservatives may be forced to listen. After all, George Osborne’s stamp duty reform was, arguably, in part a political response to Ed Miliband’s proposed mansion tax. Under Corbyn, Labour may be unlikely to win power, but Corbynmania could yet have an influence on government policy.

No comments yet