David Cameron has a vision for a “Tech City” stretching from Old Street to the Olympic Park. But as Nick Johnstone discovers, the geeks and creatives have already beat him to it

[To view an interactive guide to the area, go to propertyweek.com/techcitymap]

You might be allowed to come, but you’ll need to be fun. I will let you know by email tomorrow,” vows Divinia Knowles, chief financial and operations officer at Mind Candy, the UK’s fastest-growing digital company.

Sharp, jolly and pushed for time, Knowles is answering my request to attend the Silicon Drinkabout — an event set up by her colleague, Michael Acton Smith, to bring together local “techies”. His venue is the City Arts and Music Project — a pop-up bar at London’s Old Street interchange, or “Silicon Roundabout”, in a building due to be bulldozed by owner Derwent London next year. Two months ago, Derwent won consent to develop 300,000 sq ft of offices there, targeted at companies such as Mind Candy, which are among the UK’s new economic powerhouses.

Knowles is part of an ultra-modern East End scene full of emoticons, tweets, networking parties and co-working space. They are one cornerstone of the government’s vision to reignite UK plc. Prime minister David Cameron hopes it will become “a technology city to rival Silicon Valley” — an economic engine room connecting Old Street to Stratford’s Olympic Park, bringing together skills and ideas in a cluster of burgeoning IT-related start-ups. Office take-up from technology companies doubled in London in 2011, revealed Knight Frank’s first “Silicon London” report, published on Wednesday.

And within two months, the government will choose whether to approve plans by data centre company Infinity to occupy the giant Olympic

media centre and create a place of excellence for digital industries, called iCity. Cameron has even established a body with a £2m budget — the Tech City Investment Organisation — to help attract digital companies to the East End.

Martha Lane Fox, founder of Lastminute.com and Cameron’s digital champion, tells Property Week: “It’s an opportunity to put weight behind a cluster, with extra backing from central government — it raises our digital economy’s profile. It puts us in a better position for 20 years’ time.”

Further investigation reveals, however, a sprawling ecosystem of creative companies that has proliferated, without state intervention or Cameron’s PR bluster, for more than a decade.

His profile-raising may encourage investment, but the reaction at ground level is lukewarm.

“It was Tech City before being labelled ‘Tech City’,” Knowles sniffs. “The government has slapped a label on it, but it was all happening anyway. They may even have made it less cool for people.”

Irate bloggers describe it as a wasteful marketing ploy and a cheap attempt to appropriate other people’s achievements. When asked for a definition of Tech City’s boundaries at a conference, the investment organisation’s chief executive, Eric van der Kleij, replied vaguely that there was none.

Nonetheless, developers such as Derwent London, occupiers, and agents are eager to show Property Week the melting pot first hand.

Eclectic locals

Developer Rocket Investments, for example, will soon unveil “Silicon Way”, a new street within a mixed-use scheme on East Road, just north of the roundabout, reveals director Tom Appleton.

Earlier this month, Rocket broke the local office rent record at the 40,000 sq ft Linen House, securing a £36.50/sq ft letting to an IT recruitment business. It subsequently purchased Crown House opposite for another ambitious scheme.

Three blocks further north is Charles Armstrong, who promotes a less traditional landlord-tenant relationship. Zany, intellectual and sporting bright patterns and an asymmetric haircut, Armstrong has created 6,500 sq ft of flexible office space on Bevenden Way for start-ups. The Trampery, a name inspired by his Trampoline Systems software company, boasts recovered lamps, off-the-wall wallpaper, Chinese rugs, and as many Mac computers as the Regent Street Apple shop.

A desk costs £330 a month and comes with fresh coffee from an industrial espresso machine.

Further afield, Google is believed to in talks to prelet a 700,000 sq ft headquarters at Argent’s King’s Cross Central. But more significantly for the East End, it is sponsoring TechHub, similar to Armstrong’s “incubator” set-up.

In November, Armstrong launched the Tech City Map, an interactive programme that analyses the social media interactions of 1,125 companies in east London’s “technology ecosystem”. The Cambridge-educated sociologist now wants to ensure the state cultivates this ecosystem,

rather than stifling it.

“For planning officers in Hackney Council, the map will help make sense of what businesses need,” he says. “The most profitable thing for developers is creating space for big corporations, but that won’t help start-ups. They need 50-year investment horizons, rather than five.”

Lane Fox says: “I don’t think landlords always make it easy. They need to recognise the start-ups and help them. They need to develop big buildings that allow people to have single desk and shared space. They could encourage that more.”

Armstrong welcomes Hackney’s rules for new flexible office space, and is close to signing a 15,000 sq ft lease for another Trampery in Shoreditch.

If this is Shoreditch’s new blood, the trailblazing geriatric is Starprop, the area’s largest landlord, which has developed there since the 1970s. The company’s Alex Bard says the occupier landscape has “altered massively” in the past three years. Tech start-ups, such as those cultivated in the Trampery, have “gobbled up creative-type studios”, pushing the artists that first colonised the neighbourhood to cheaper areas such as Dalston and Hackney Wick.

This is the kind of growth espoused by Tech City UK, but Appleton is cynical about the impact of branding: “Clustering technology businesses has had an impact on everyone here, but we didn’t come because it was called Silicon Roundabout.”

Nonetheless, he reckons understanding these occupiers is crucial. Creative “hipsters” want bare brick and warehouse-style interiors. Per square foot, this is inevitably cheaper than slick City fit-outs.

Stylish schemes

East End style comes from years of artisan culture in Shoreditch — traditionally home to artists, radicals and furniture-makers, as well as printers serving the City. Modern occupiers still need low-cost space and want to see — and be seen in — the trendiest locations, such as Hoxton Square.

Local property is therefore dominated by less corporate agencies. Hatton Real Estate, Allsop, Stirling Ackroyd, Thompson Yates, Anton Page, Richard Susskind and CF Commercial understand the vagaries of a location that, in reality, emanates from further east than the much-vaunted Silicon Roundabout.

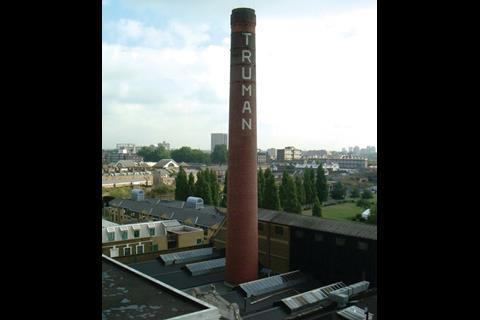

It started in the late 1990s at Brick Lane’s 19 acre Truman Brewery. As the dot.com bubble inflated, technology companies clustered around “nodes” of broadband strength. Brick Lane had six fibre-optic providers, which was enough to lure a wave of edgy start-ups — thirsty for bandwidth — to the area.

Twenty years ago, the brewery was reportedly valued at £5m. Now a busy warren of bars, shops, restaurants and event spaces — as well as more

than 200 businesses — it is worth closer to £150m.

Old Street Roundabout was another broadband node. For nearly two decades, the two locations have formed a creative axis just north of Spitalfields and Aldgate. Research suggests there are now 3,000 creative occupiers in EC2.

Derwent co-founder Simon Silver seems to agree that the creative industries are taking up slack left by more traditional sectors. Last month, law firm CMS Cameron McKenna pulled out of 200,000 sq ft prelet talks with Hammerson at Principal Place, where the City of London meets Shoreditch, citing “financial volatility”.

From now on, these fringe areas are no longer solely the preserve of traditional occupiers. If so, bullish Derwent will cash in. It developed the trendy Tea Building further north, where Mind Candy took 7,600 sq ft for its headquarters a year ago. It has since more than doubled its floorspace. The eight-year-old gaming company created online phenomenon Moshi Monsters, boasts 100 million customers worldwide and has quadrupled its turnover each year.

“These 25-to-35-years-olds are so creative,” Silver says. “I often don’t understand what they do, but they have great balance sheets and they hardly care about the wider economy.”

Silver is anxious to retain them as they expand and mature. His “White Collar Factory” at 100 City Road is one option. He envisages a “vertical Silicon Valley”, encouraging osmosis of talent throughout the 200,000 sq ft building. It will be surrounded by flexible “incubator space”, creating a veritable production line for growing start-ups.

The idea is less idealistic than it sounds: Truman Brewery has shown that “clustered” tech companies do interconnect and innovate together. Silver plans to visit Silicon Valley to learn how to encourage this.

Derwent, Rocket, TechHub, Starprop and others have also adopted a collaborative spirit, creating a body called Independent Shoreditch and offering to pay for an Allford Hall Monaghan Morris-designed, multimillion-pound overhaul of Old Street Roundabout. Its central turf will be turned into an event or public space.

Investment co-ordinator Ben Davies runs the project and wants a business improvement district-type area that resists the uncool term “BID”. His grassroots plan is Cameron’s Big Society in practice — no section 106 payments here — and is not affiliated with Tech City.

At the other end of the axis is the Olympic Park, where the iCity consortium, advised by Drivers Jonas Deloitte, has grand plans. Chief marketing director Nigel Stevens claims it could provide “critical, advanced infrastructure to east London’s booming and rapidly expanding creative sector”.

The Trampery’s Armstrong — who has been advising iCity on how tech start-ups work — says the process is a “massive challenge” that “has the most potential of the three”. He calls Hackney Wick a “ferment of artists in cheap industrial space”.

He says: “Either bland corporate Olympic stuff will squash the artistic thinking, or it will go in the other direction. But there is a risk that the media centre becomes like an out-of-town science park.”

Whatever happens, the hands-off coalition must stay true to its word, even when PR points are on offer. In the end, Divinia Knowles’s email about the Drinkabout fails to materialise. Better, perhaps, to leave this brave new digital world undisturbed.

To view an interactive guide to the area, go to propertyweek.com/techcitymap

No comments yet