Northern Ireland’s property market has had a turbulent history. Noella Pio Kivlehan assesses the impact of the Good Friday Agreement two decades on from its signing

A quick internet search for 1998’s top news stories brings up one dominant topic: Northern Ireland’s Good Friday Agreement (GFA). Signed on 10 April that year, the GFA marked the start of the end of 30 years of conflict in the province of Ulster that had claimed more than 3,500 lives.

Suddenly a huge and largely untapped UK market with a population of 1.7 million was open for business. For the province’s commercial property sector, which had been the poor cousin of mainland UK due to ‘the Troubles’, there was the chance to see investors coming in, development happening and occupiers – local, national and international – take space.

But in the two decades since the GFA, Northern Ireland has experienced highs and lows unparalleled in the rest of the UK – primarily because it had come from such a low base: in 1998, Belfast office rents were stagnant at £10/sq ft, compared with £32/sq ft in Manchester, for example.

So what did the signing of the GFA do for Northern Ireland’s property market? And now that the collapse of Stormont and Brexit threaten stability, how is it expected to fare in the years to come?

As lauded as the GFA is, for some the pivotal moment of stability came to Northern Ireland a few years earlier. “The economic impact of the 1998 agreement per se was smaller than sometimes thought,” says Dr Esmond Birnie, a senior economist at Ulster University Economic Policy Centre. “Some improvements in trend were already under way in the early- to mid-1990s. The ceasefires and the subsequent political agreement may have helped maintain an economic improvement that was already starting to show.”

The economic impact of the 1998 Agreement per se was smaller than sometimes thought

Esmond Birnie, Ulster University Economic Policy Centre

Martin McDowell, managing director of Belfast-based agency Osborne King, agrees. “The most definitive and defining moment from a property point of view was actually in 1994 with the ceasefires. It meant a lot of the problems we had with buildings being damaged or destroyed fell away. The political progress of the GFA was very welcome but the semi-official cessation of hostilities was the more dramatic point for us.”

Peace and political stability had a marked effect on almost all property sectors but primarily on residential, office and retail and leisure, the last almost instantly. The province’s number of annual leisure visitors almost doubled between 1998 and 2017 from1.4 million to 2.7 million and from 1997 the retail sector saw an influx of large UK retailers, namely supermarket chains Asda, Sainsbury’s and Tesco.

Their entrance certainly created competition with firmly established local chains such as SuperValu. “Their entry shook up the market,” says Glyn Roberts, chief executive of Retail NI, which represents 1,800 of the province’s independent retailers.

‘Strong indigenous economy’

Added to this was significant growth in activity from local investor/developers who acquired or invested in retail assets such as Forestside Shopping Centre in Belfast, Abbey Centre in Newtownabbey and Bloomfield Shopping Centre in Bangor.

“Retail during that time was very strong,” says Jago Bret, a director at GVA NI. “There was a strong indigenous economy. People spent more of their disposable income on having a good time… and that was a legacy of the Troubles, because you didn’t know what was around the corner.” As for the office sector, Bret says the first wave of investment and development was driven by demand for call centres. “We were trying, like a lot of regional centres, to capture that market,” he says.

Offices were developed primarily by local companies such as McAleer & Rushe and McLaughlin & Harvey. “It was the local guys who really knocked up the big buildings,” says Gavin Weir, Bret’s fellow director at GVA NI.“They really seized the opportunity. What comes across is that [development] was all market driven.”

Brexit and Northern Ireland’s border issue

In June, CBRE published ‘Brexit and Northern Ireland: A guide for real estate decision makers’. One of the report’s authors, Miles Gibson, head of UK research at the firm, states: “We do think there will be a deal on the withdrawal agreement, which is likely to resolve all the issues around money, citizens’ rights and Northern Ireland. It will be agreed quite late in the day and it will be complicated but we do think there will be a deal.”

Gibson – who believes there’s a 25% chance of a ‘no deal’ outcome – says that businesses operating on both sides of the border may not have certainty at the point of exit on 29 March 2019. Instead, they will “have to wait until the end of the transition in December 2020, by which time all the detail should be sorted out”. He adds: “We are not of the view there will be a cliff edge at the end of either March 2019 or December 2020 – something will be hammered out.”

From the agency side, Brian Lavery, managing director of CBRE in Belfast, says he has so far seen no Brexit border jitters from retailers, occupiers or investors. “Look at the office market,” he says. “We’ve had our strongest-ever half year with more than 500,000 sq ft signed in the first six months of 2018. That doesn’t give any indication that [companies aren’t active] because of Brexit.”

National and international investors who had been in the province pre-GFA, but who had pulled out, felt comfortable enough to return. “Companies that came back in were the likes of Threadneedle and CBRE NI,” says Brian Lavery, managing director of CBRE in Belfast. “Then development decisions became an economic question rather than a locality question. When the sums added up, development happened.”

Then it all fell apart. “Just when we were seeing everything going well, the crash happened,” says Lavery.

For Northern Ireland, having gone from such a low base pre-GFA to a boom market within 10 years, the 2008 recession was close to catastrophic. “It really decimated Northern Ireland beyond anywhere else [in the UK] because we were on that wave,” says Lavery. “The GFA was making everything move forward, then recession came.”

Average house prices in the province that had rocketed from £100,000 to £250,000 within 10 years of the GFA suddenly dropped by 60%. “In other parts of the country, you would have

Average house prices in the province that had rocketed from £100,000 to £250,000 within 10 years of the GFA suddenly dropped by 60%. “In other parts of the country, you would have had a 20% to 30% fall,” says Lavery, who adds wryly that “the recession wouldn’t have been as much of a cataclysmic affair if we hadn’t had that quick growth because of the GFA”.

Turning point

The general consensus is that it wasn’t until at least 2014 that the province really started coming out of recession, with the turning point being the sale of the National Asset Management Agency’s (NAMA’s) $1.6bn (£1.3bn) Northern Ireland loan book, Project Eagle, to US firm Cerberus.

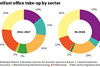

Over the four years since, there has been a return to growth, particularly in student accommodation – some 3,000 beds have been added to the market – and in the office sector. The office market has seen its strongest-ever half-year take-up with more than 500,000 sq ft signed in Belfast since January. Development is also under way, including Oakland Group’s £70m nine-storey Merchant Square in Belfast, construction of which began in May.

However, just as stability was returning to the Northern Irish market, it was forced to confront two new major challenges: Brexit and the lack of a sitting executive in the devolved Northern Irish parliament, Stormont.

When the UK voted to leave the EU in June 2016 – Northern Ireland voted to remain – few envisaged the uncertainty or questions over the Northern Ireland/Republic of Ireland border (see box).

More locally, Sinn Fein walked out of the Northern Irish assembly in January 2017, bringing about its collapse. The assembly was set up after the GFA and took on myriad legislative responsibilities including economic development, health and education. Since January, there has been no authority to commission public sector work and no one to give ministerial approval for the development of large schemes.

To a certain degree, Northern Ireland is so battle-hardened to all the political shenanigans

Market commentator

Market commentators point to victims such as the £46m 250,000 sq ft City Quays 3 scheme – part of Belfast Harbour’s City Quays masterplan, which has stalled – and infrastructure improvements including the York Street interchange to join the M1 and M2 to create free-flowing traffic through Belfast.

It is thought the assembly will once again try to come to an agreement in the autumn. But as one market commentator says: “That doesn’t mean anything. There’s just no confidence from the business community. There’s apathy here.”

He adds: “To a certain degree, Northern Ireland is so battle-hardened to all the political shenanigans that people are good at just getting on with it. Politicians are stopping us doing what we want to do, but we’ll find a way around it.

“One of Northern Ireland’s greatest strengths is the people’s resilience in business and it stands them in very good stead.”

It is that same resilience that has stood the province in good stead over the 20 years since the signing of the GFA. And the hope is that it will carry it through into a prosperous – albeit currently uncertain – future as well.

Ireland supplement: two decades on from Good Friday Agreement

- 1

- 2

- 3

Currently reading

Currently readingGood Friday: 20 years on

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

No comments yet