Urbanisation plus humanity equals ‘Urbanity’. This hybrid will be one of the major themes of this year’s Mipim. It is a simple equation, but its principles are at the heart of the biggest questions facing the property sector.

The number of people living in cities is growing exponentially, but where are they going to live when space is so limited? People are going to cities in search of jobs, but where are they going to work? Finally, is infrastructure ready to meet these needs in the UK?

These are big questions for society and the implications will be felt across the whole real estate sector.

The move from agricultural and pastoral lifestyles towards city living has been under way in the UK since the early 1800s and continues apace globally. According to the latest UN projections, 66% of the world’s population are expected to live in cities by 2050.

That’s 66% of a population that will have increased from today’s 7.2 billion to 9.6 billion. The pace of urbanisation is picking up and is putting pressure on cities as well as on the developers tasked with building the infrastructure and real estate required. That’s especially the case in megacities like London (pictured) where GDP is nearly that of the whole of the Netherlands.

Is it sustainable for cities that were designed 300 to 400 years ago to continue to meet the needs of a growing populace?

So how are we going to effectively house all the people who want to live in cities? If we’re putting buildings up faster than we ever have before to meet demand, do we then face increased risks of moving too fast?

The tragic incident at Grenfell Tower last year was the most shocking example that meeting the minimum standards still encompasses risks. From a moral standpoint, developers have to ensure standards do not slip amid pressure to build quickly. All developers must now look at risk more widely. Willis Towers Watson has a range of resources, including a full ‘mock trial’ scenario, to support firms to fully understand the dynamic between risk tolerance and the performance of risk management programmes when executed.

Sustainability is another core theme of urbanity. Is it sustainable for cities that were designed 300 to 400 years ago to continue to meet the needs of a growing populace?

That’s particularly true for places, like London, that reach megacity status. The M25 motorway is forever playing catch-up to the demands of road users. Each day, close to 200,000 vehicles venture on to the M25 – a number that far exceeds the 88,000 vehicles it was intended to tolerate when it first opened 30 years ago.

Significant infrastructure tends to be about 50 years behind demand. So commercial and residential developers have to consider whether they are building sustainably for the decades to come. If construction is taking three to five years to complete, will it meet the expectations of what the city needs in three to five years’ time? This raises the question of what future regulation will be needed to ease the bureaucratic burden on developers and allow them to deliver infrastructure that predicts demand rather than reacts to it.

Another consideration is the overall placemaking of an area. Are the amenities, retail and commercial offerings a good match with the mix of local residents? It can become less of a sustainability debate and more of a sociological one, but projecting whether local users will be long-term regular users of an asset or will seek alternatives further away is an important risk to consider.

Developers also face a unique set of risks in areas such as London. The risks surrounding a construction site have never been greater. Not only are the threat of geopolitical instability and an ageing workforce creating a volatile environment, but the drive to build in parts of cities that would not previously have needed developments increases the risk of encountering archaeological finds. There is lots of historic ground around London and any discovery can cause significant delays to a project and sometimes even abandonment.

There is also the human risk involved in any scheme. Negligence from employers is high on the list of possible causes of an interruption to the property lifecycle. All it takes is one incident of an employee being injured on site and the company responsible can be damaged for a long time. Mitigating and managing that risk is key to extending the property lifecycle.

Proptech factor

The next step along the way is proptech and how the development of technology is starting to affect the construction and concept of a building.

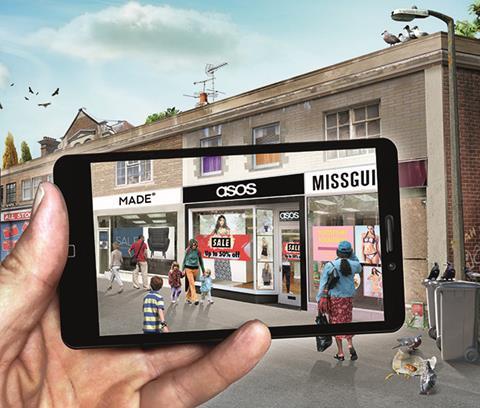

From an urbanity perspective though, perhaps an even bigger risk consideration is the advancement of technology. The continued growth of online retailing at the expense of high-street shopping, for example, has resulted in the need for more and more logistics facilities close to urban areas to serve the high volume of home deliveries.

People continue to move to cities in greater numbers and are also increasingly buying online rather than on their local high streets. As a result, huge warehouses are becoming the new shopping centres.

Developers and retailers are increasingly finding that while they no longer need big high-street stores, they do need a major distribution centre. Consequently, demand for logistics space on the edge of cities is on the rise. High streets in city centres face a hugely uncertain future and footfall will continue to suffer as online retail grows.

Urbanisation brings considerable opportunities for the property sector but also increased challenges and risks. As more people move to cities, where are they going to live? Where are they going to work? Is infrastructure ready to meet these dual needs?

Risk mitigation and sophisticated risk transfer concepts will increase in relevance as urbanisation continues to have an impact. It’s a brave new world; we must not rush to make it happen at the expense of sustainability.

Mark Noble is executive director, real estate practice at Willis Towers Watson

About Willis Towers Watson

- A deep history dating back to 1828

- Willis Towers Watson is one of the world’s leading insurance brokers for the construction industry

- We work with 78% of Fortune Global 500 companies

- Willis Towers Watson has teams in more than 140 countries

- We design and deliver solutions that manage risk, optimise benefits, cultivate talent and expand the power of capital to protect and strengthen institutions and individuals

Topics

PW Perspectives – Mipim 2018

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

Currently reading

Currently readingUrbanisation poses risks for the property sector

- 9

- 10

- 11

No comments yet