The government has set a target of delivering one million new homes by 2020.

It’s a target that even a generous commentator might describe as optimistic, unless a new source of delivery can be mobilised.

UK plc is struggling to deliver 150,000 homes a year (that’s 750,000 by 2020), so unless we can find a new source of funding and delivery the target won’t be met. That also assumes the delivery system doesn’t catch a cold – which is again optimistic considering the current City trend of shorting some housebuilders.

Since the 1980 Housing Act, which withdrew local authority funding and introduced section 106 obligations, councils have been out of the game of delivering housing, leaving a supply gap. The public sector can’t fill it without renewed funding, and the private sector will not flood the market with cheap flats.

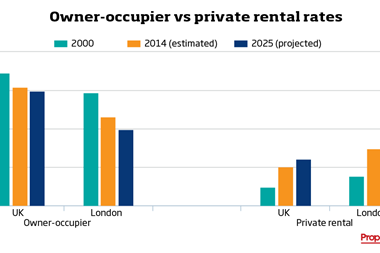

The government is fixed on its mission to deliver universal home ownership with its ‘starter homes’ and Help to Buy initiatives, but are these deliverable and sustainable? The average first-time buyer in most central London boroughs will have to spend £400,000 (the average home in London is £514,097). Even assuming generous parents can stump up £100,000, the remaining £300,000 will need to be covered by a mortgage, which at 3% will cost £750 per month. If (or when) interest rates go up to, say, 5%, this figure jumps to £1,200 a month. Now add bills, insurance, repairs and service charge on top of stamp duty and legal fees. How sustainable is that? Recent research from PwC predicted that 60% of Londoners would be renting by 2025 – suggesting not particularly.

Build-to-rent is a solution to filling the gap in affordable supply, but the sector lacks government support and is battling negative perceptions left by the rental market. My company’s recent survey on renters in London and the South East showed that most of them have unrealistically high expectations of home ownership, and do not see renting as a viable long-term option. When asked how long they expected to live in rental accommodation, 66% of respondents said less than five years (75% for 25-30-year-olds). Among those expecting to rent for more than five years (34%), satisfaction was at an all-time low, with only 15% happy to rent for that long.

A positive choice

Yet if 60% will be renting by 2025, this attitude must change. The build-to-rent sector is committed to increasing supply and providing a service quality that makes renting a positive long-term choice. Home ownership is a fine aspiration, but to those for whom it is not possible, rental is everything.

There is an opportunity to embrace the £50bn of institutional investment available to fund new build-to-rent blocks. Each scheme should be looked at as if it were a standalone enterprise zone, which, in return for a 10-plus-year covenant, is granted planning certainty. The covenant would ensure the building remains as a long-term rental asset, and would define the quantity and level of any discounted market-rent flats, which would take the place of affordable units. The planning certainty would enable rapid delivery.

Renting is here to stay, and improvements to stock, management and amenity will drive the sector. But we need support to improve things for the next generation.

Harry Downes is MD of Fizzy Living

No comments yet