If there has been a positive outcome of the credit crunch it is a change in our attitude to housing.

There is now a genuine realisation of the issues facing young people trying to get onto the housing ladder and a much greater focus on increasing housing supply.

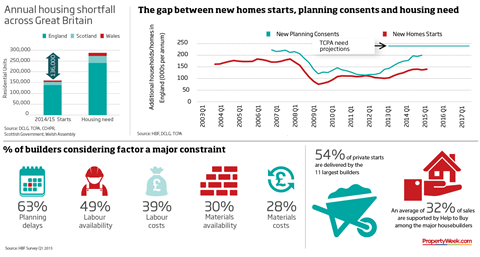

There are clear challenges to delivering the housing we need in a more regulated mortgage market - especially given the strong historic relationship between transaction levels and levels of housebuilding.

Various incarnations of Help to Buy have sought to counter the deposit affordability issue faced by those seeking to get on or trade up the housing ladder. These measures have drawn criticism from those espousing the risks of stoking demand without a supply-side response.

So against the localism rhetoric, it has been interesting to see central government seek to intervene where local plans are not in place by 2017 and open up the planning system where local authorities do not have a five-year land supply.

This has started to pay dividends, with planning consents increasing substantially as the market has improved. But it will be a while until this translates into starts and completions, given shortages of labour and materials and a reliance on a relatively small number of large housebuilders.

Initiatives such as Help to Buy and the Starter Homes scheme, in part at least, reflect a political fixation with home ownership, which has led to a strong emphasis on building homes for sale. While these schemes clearly have an important part to play, there is a danger that housebuilders become overly reliant on such schemes and we lose sight of the need to build the right types of property in the right locations across a range of tenures to meet the diverse needs of society.

Whatever the desire to give as many people the opportunity to own their home, we need to build for rent as well, given the underlying shift away from mortgaged owner-occupation. In reality government policy, such as restricting the tax relief available to buy-to-let investors on mortgage interest, can only go so far in tempering this underlying trend. So the case for institutional investment in the private rented sector grows. More than ever it needs a stimulus to get it moving.

At the other end of the spectrum we have a growing elderly population sitting on a significant pool of equity in housing, which they often under-occupy and which is regularly ill-suited to their future needs. Much greater emphasis is needed to deliver more housing that encourages them to downsize, especially given the proposed changes to inheritance tax.

In both cases planning has a critical role to play in recognising and accommodating these needs at scale.

At the heart of this is a need to understand the nature of demand for housing, which goes beyond a simple one-dimensional numbers game.

The industry, with help from government, then needs to develop the models that establish how a wider range of housing can be delivered in a financially viable manner. The use and co-ordinated release of surplus public land is important in assisting in this process. By providing a lead on land assembly, funding of infrastructure and new models of delivery it could contribute more than just the homes that it accommodates.

Lucian Cook, Director of residential research, Savills

No comments yet