Fashion, much like property, is cyclical. Ideas inevitably fall out of favour, only to be resurrected years later, usually sported by gloating youngsters.

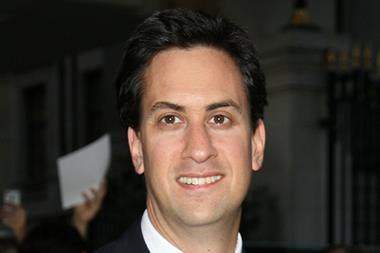

Ed Miliband, then, is the rather unlikely leader of a 1970s fashion revolution. Rather than flared jeans or tie-dye t-shirts, it’s that most clumsy of policy instruments - rent controls - he wants to reinflate.

Last year, Labour promised to cap rent increases and scrap letting fees as part of a “fairer deal” for the soaring number of private renters.

As with Labour’s energy price promises, rent controls are a seductively simple solution to a complex problem. The problem is that vilifying landlords will not lead to more homes being built. But with the reputation of landlords up there with payday lenders in certain parts of the media, it is no surprise that polling by campaign group Generation Rent found just under two-thirds of the public support some form of rent control, with only a measly 6.8% opposed.

Labour mayoral hopeful Diane Abbott recently joined the fray, while respected think tank Civitas claimed Miliband had not gone far enough.

The key point here is that posing rent controls as the solution deliberately conflates various issues around supply, service standards, trust and affordability.

Clearly, there is a widespread feeling that rents are too high. But rent controls are not the answer, just as landlords are not to blame for a lack of housebuilding during successive Tory and Labour governments.

Proponents of rent controls usually point to Germany, whose economic model is in vogue in Britain’s political circles as a successful example of rent controls being implemented.

However, Germany has a huge supply of regulated rental homes, which has suppressed costs. Housing costs are relatively low: average rents in Munich - the highest in Germany - are just one-third of average rents in London. Most Germans spend less than 30% of their income on housing, whereas some Londoners spend half their income or more.

Legislation restricts rental increases for existing tenants, which is what Miliband and co want. But this is not the real reason why rents are lower in Germany - far from it. The real reason is that Germany builds far more homes than we do - in 2013, the most recent year comparable data is available, Germany built 225,000 houses, compared with the 109,000 homes completed here.

Unfortunately, the debate around our national inability to build houses has focused almost exclusively on the impact it is having on first-time buyers, who are now forced to live with mum and dad, or rent.

The government has invested £1bn in a Build to Rent Fund and promoted the need to get institutional investors building a European-style, family-oriented rental market here. But this fledgling industry is in its embryonic stages and Miliband’s meddling threatens to spook investors before they have had a chance to really make things move.

Many professional landlords are already offering long-term tenancies with fixed rent increases over three years. But imposing a model that is insensitive to market conditions will cause investors to look twice, compounding the problem with supply, and in turn, pushing rents up even higher.

So, far from creating a more affordable, secure private rented sector, rent controls threaten to do the very opposite. It will be renters who suffer most - not landlords.

Julian Goddard is head of residential at Daniel Watney

No comments yet