In the immediate aftermath of the Grenfell Tower fire last year, a number of local authorities sent samples of aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding taken from council-owned buildings to a government testing lab to ensure the material did not present a fire risk.

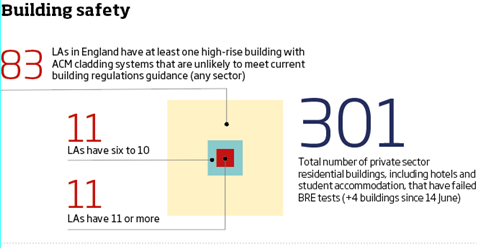

Just after the tragedy, the government reported that 60 high-rise buildings across 25 different local authorities had failed a combustibility test at the Building Research Establishment (BRE).

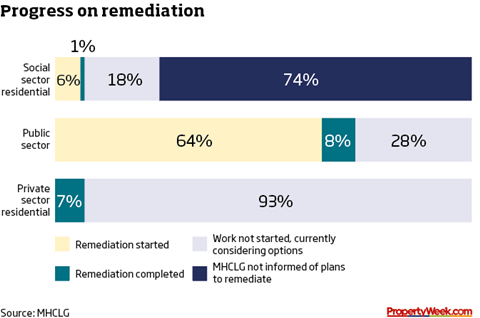

At the time, Property Week reported that the potential cost of replacing the cladding – calculated by Gleeds – could be as high as £12bn. Since then, remediation work has started on 114 of the 159 social housing blocks exceeding 18m in height that are in England, managed by local authorities or housing associations and failed fire safety tests. Work had been completed on 13 buildings as of 12 July this year.

However, there is less clarity over the extent to which private-sector-owned buildings are affected. According to figures published in July by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) in England, 301 private sector residential buildings (including hotels and student accommodation) exceeding 18m have been identified as having ACM cladding systems unlikely to meet building regulations guidance.

The department says that it is “currently working with local authorities to collect data on private sector buildings with ACM cladding” and that “this data will be published in due course”. Ditto data on the remediation of private sector buildings.

In an attempt to gain a fuller picture of how big an issue ACM cladding in the private sector is, Property Week sent a freedom-of-information (FOI) request to every London borough asking: ‘How many private residential blocks over 18m with ACM cladding have been identified in the borough area to date?’ We also asked for addresses. The responses make for fascinating reading.

Find out more - Scores of privately owned blocks in London clad in ACM

Of the 33 London boroughs contacted, 31 supplied a response within the stipulated timeframe of an FOI request. Of these, 14 said they had identified one or more properties with ACM cladding, amounting to 86 properties; nine said they had no properties with ACM cladding; and eight declined to answer our request.

The London borough containing the highest number of buildings with ACM cladding was Greenwich with 29. This was followed by Brent and Wandsworth (both 12), Hounslow (six) and Croydon (five).

Towers of London

Some local authorities were more forthcoming with information than others. For instance, Croydon confirmed that although there were no council-owned buildings with ACM cladding in the borough, it said five privately owned and managed buildings had been identified as having ACM cladding.

“Of these, two have had cladding removed, two are planning the removal of category-three ACM and one has limited category-three ACM where London Fire Brigade [LFB] has agreed that there is sufficient fire prevention equipment to be considered safe,” said Croydon’s FOI co-ordinator.

In Islington, the local authority has identified 144 buildings in the private sector that are “likely to meet the definition of a tall building as set out by the MHCLG, and one housing association property; three buildings have ACM cladding and 17 remain under investigation”.

Some local authorities split the data they supplied into subsections based on level of severity. Hounslow’s information commissioner’s office said it had identified four “privately owned residential high-rises substantially [maybe 50%-plus] cladded where the presence of ACM was confirmed by test or accepted in writing by the owner”, two buildings that were “unsubstantially [maybe less than 50% cladded]”, where the presence of ACM had been confirmed, and three privately owned residential high-rises “cladded in a material that could be ACM that is not yet confirmed by test or accepted in writing by the owner”.

While most local authorities did not have a problem revealing the number of buildings within their borough that failed the test, they were less forthcoming when asked to supply addresses of these buildings, citing a number of factors.

For instance, although Lambeth confirmed it had identified two residential blocks with ACM cladding that had been “checked by the fire brigade and in LFB’s opinion have satisfactory measures in place to remediate”, the borough declined to disclose the location of these buildings as it argued that it might be “detrimental to the interests of the person who supplied us with the information”.

Locations withheld

The statement from Lambeth’s information commissioner’s office continued: “The information was provided in relation to fire safety tests being undertaken in light of the Grenfell Tower tragedy. The organisations concerned were not legally obliged to report the information to us and did not supply it in circumstances that would allow us to disclose it.

“Disclosure of the information would likely cause harm/distress to the third party and we consider it unlikely that they would consent to disclosure.”

Wandsworth, which identified 12 buildings in the borough with ACM cladding, put forward a similar argument, stating: “The council believes that information provided to the council in good faith by building owners was provided in confidence – building owners had the expectation that information provided to the council about their buildings would not be made public.

“Where fire safety tests have been carried out, building owners are in discussion with residents in those buildings about how to proceed.”

Hackney, which said it had identified four privately owned residential blocks with ACM cladding, argued that it was not in a position to release the addresses of the blocks as it was personal data and was therefore exempt from the FOI Act.

Meanwhile, the borough of Islington said it intended to publish a redacted list of buildings that “meet the definition” on its website in due course, but did not intend to “identify the buildings by providing their full address or postcode” or to “identify the owners [of the buildings]”.

While some boroughs were reluctant to divulge ownership and address details, others declined to supply any of the information we requested.

Newham refused to provide data, explaining: “We have and continue to work alongside private owners in compiling and verifying the requested data. Any residents within individual blocks will be updated and informed locally of any safety issues which may be applicable to their blocks and the specific resolutions to be put in place.

“We do not believe it is in the public interest or in the interest of those living at these locations to disclose this information in mass format publicly under the provisions of the act.”

A similar argument was put forth by the City of London (CoL). “While acknowledging that, for public safety reasons, there is a public interest in knowing the location of buildings with ACM cladding, the CoL considers that the risk and consequences of any criminal use of the information could be so extreme as would outweigh the consequences of the information not being publicly disclosed.

“We would note that the owners of the buildings are already aware that such cladding has been used and have been working closely with the relevant departments to put in place an agreed fire safety plan. Therefore, the CoL considers that the public interest in non-disclosure outweighs the public interest in disclosure of the identification of the buildings.”

The City of Westminster was also reluctant to supply information. “Following advice from the MHCLG, the council has been asked to withhold this information, as it believes there are public safety risks associated with releasing information, such as comprehensive lists, that allows buildings with cladding, which is likely to present a hazard, to be easily identified.”

As for the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC), where Grenfell Tower is located, the information management team confirmed it held the requested information, but said it was withholding it in the public interest.

“We recognise that there is public interest in the release of this information for transparency and accountability reasons. However, it is not in the public interest to disclose information which could lead to public safety risks as disclosing the requested information will allow buildings with likely hazardous cladding to be identified.

“The council follows MHCLG advice on not releasing this kind of information. It has therefore been concluded that the public interest lies in withholding the information.”

Both the City of Westminster and RBKC cited MHCLG advice issued to local authorities in a letter dated 29 November last year in which it said it believed there were public safety risks associated with releasing information about buildings with ACM cladding.

It is therefore unlikely that we will ever get a clear picture of how many privately owned residential blocks are affected. Equally difficult to establish is how the private sector buildings in London that are affected are being remediated because of the reluctance of the majority of local authorities to supply address details.

Information disclosure

One east London council did supply the postcode of a block where a series of interim measures had been put in place, but Property Week decided not to disclose the location for the reasons cited by the MHCLG. What we can disclose is that the measures include a 24-hour waking watch, smoke and heat detection in flats and communal areas as required by the fire brigade and communal windows adjacent to the affected cladding being sealed. The local authority added that about 30% of the cladding would be replaced with A1-rated cladding, which is wholly non-combustible. Work is expected to commence in September this year.

We also contacted the landlord of a building fitted with ACM cladding in south London, which has already implemented a series of interim fire safety measures and started work on replacing the cladding. “We are focused on completing the work as soon as possible and, above all, ensuring it is done to the right standard so the building is safe for the future,” said a spokesperson for the landlord.

Also in south London, the landlord of two high-rise blocks said it had replaced their ACM cladding in June and that the work had now been signed off by building control.

“We decided to remove the previous cladding, which, although not the same make as used in Grenfell Tower, was a similar design and covered only 20% [approximately] of the building,” said the landlord’s director of property services, adding that leaseholders were not charged for the replacement and that the landlord remained in close contact with residents to keep them fully updated throughout.

We also spoke to another landlord in south London, which stated it had taken immediate action to review the fire safety measures at one of the buildings under its ownership and submitted a sample of the cladding for testing following the Grenfell fire.

Since the sample of the cladding did not pass the fire safety test and was assessed as category-two ACM, the guidance from the MHCLG was to seek an expert opinion on whether the cladding should be removed.

The landlord’s director of operations said that “with the control measures and fire safety system we have in place, the building was considered safe and no further action was recommended”.

The director added that the building had a sophisticated fire detection system with sensors and audible alarms in all rooms, staff on site day and night to manage any evacuation and regular inspections carried out.

“The safety of our customers is our top priority,” said the director. “Now that the government fund for the replacement of cladding has opened, we are seeking guidance and clarity on whether category-two ACM is eligible for this. We will continue to take advice from LFB and guidance from the MHCLG.”

True scale of the problem

While these companies readily accept expert input and are making the necessary investment, not everyone is as proactive. One borough’s FOI officer said it was sometimes difficult working with the private sector – “a bit of a cat-and-mouse game”. Persuading landlords to pay for the replacement of cladding was akin to “getting blood out of a stone”, he said, adding disparagingly: “How can somebody be so protective of their profits?”

Although 301 private-sector-owned high-rise buildings with ACM cladding have been identified to date, the true scale of the problem could be far worse. As the MHCLG’s latest building safety programme update shows, the cladding status of approximately 100 private sector residential buildings is still to be confirmed.

The department says enforcement notices have now been issued to landlords and that, based on current evidence and the identification rate to date, it expects 3% to 5% of the remaining buildings to have similar ACM cladding systems to those that have failed BRE tests.

A spokesperson for the department adds that fire and rescue services are working with the building owners to ensure people are safe and that it has written to owners to remind them of their responsibilities. “The safety of residents is a top priority and ministers have been clear that building owners are responsible for ensuring their buildings are safe,” says the spokesperson.

Meanwhile, a new private sector remediation taskforce has also been created to oversee a national programme of remediation in the private sector and to ensure plans are in place for every building affected. And an inspection team, backed by £1m in government funding, has been established to help support councils to boost their capacity and expertise so they can undertake enforcement action and ensure building owners speed up the remediation process.

In short, while there may not be a great deal of transparency yet over the scale of the cladding problem in the private sector, there soon could be – and even if landlords don’t have to publicly disclose which of their buildings are affected, or where they are, they will be expected to carry out the appropriate remediation work. You would hope they would.

After all, no one wants to be responsible for another Grenfell.

1 Readers' comment