Part two of a potted history of property. Penned to give a sense of perspective of what might be coming, given a downturn. Last month told of redundancy fears among agents. This month mulls the future for office values, given profound changes in demand.

Landsec and British Land have been chosen as examples, mainly because their halcyon year records from 2006-07 can give perspective; but also, because it shows their relative decline over a period when sector specialists have burgeoned.

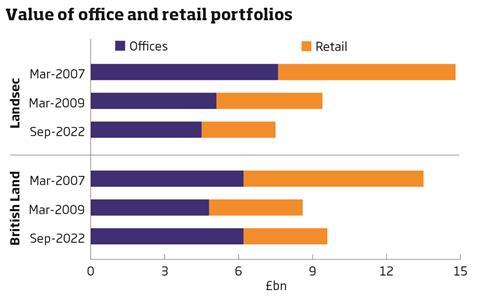

Real estate investment trusts (REITs) began life in Britain in January 2007. No more capital gains tax would stimulate development was the thinking. Landsec immediately became the third-largest REIT on Earth, behind Westfield and Simon Property, holding offices worth £7.6bn and shops valued at £7.2bn. Then came the recession.

By March 2009 the office portfolio had shrunk to £5.1bn, retail to £4.3bn. A loss of £5.2bn was declared. Shares were sold at 50% discount to raise £755m. Thirteen years later, Landsec holds £4.5bn of offices and £3bn of retail.

In March 2007, British Land held offices worth £6.2bn and shops valued at £7.3bn. Then came the recession. By March 2009, the office portfolio had shrunk to £4.8bn and the retail to £3.8bn. A loss of £3.9bn was declared. Shares were sold at a 54% discount to raise £740m. Today, British Land holds £6.2bn of ‘Campus’ offices and £3.4bn of retail. Note: the cost of goods and services has risen by 50% since 2007. But office rents and thus values have barely moved for decades.

REIT status discourages sitting on stock. Both companies are in better, slimmer shape to face a downturn, which has seen them mark down their assets by 3% in the past six months. Landsec’s loan-to-value ratio is today 34% – half the level entering the last recession. British Land’s LTV has dropped from 48% to 33%. Both are, therefore, well placed to weather a fall in values. As are other grade-A firms, such as Derwent London and Great Portland Estates. But there is a still this widespread assumption that as long as you accommodate ‘green shift’ occupiers, demand and values will hold up – for a bit, perhaps.

Prime retail was supposed to hold up in the face of the online onslaught. Last December, Landsec paid £172m for a 25% stake in Bluewater, valuing the Kent shopping centre at £688m, less than one third of its £2.2bn valuation in 2014. “There is a significant parallel with where the retail market was five years ago,” said Cushman & Wakefield UK chair Digby Flower in his retirement speech at the Armourers’ Hall last week. The City agrees. Shares in Landsec and British Land are trading at a 50% discount to their net asset value.

Blocks with no future

Hybrid working means green shifters typically need 30% less new space than in the old place. Old offices need to hold a minimum ‘E’-rated Energy Performance Certificate by April. In 2027, the bar rises to ‘C’, then ‘B’ in 2030. This is leading to the creation of what Americans call ‘zombie’ offices: half-empty, financially dead blocks, unviable to upgrade. There are thousands of zombie blocks with no obvious future. Obsolete space that will likely act as a drag anchor on grade-A space for years to come.

In New York, zombie blocks make up 40% of the office stock. Owners holding out for book value are starting to crumble. Cushman & Wakefield’s capital markets boss, Doug Harmon, told the FT last week “there is a consensus feeling that capitulation is coming”. Not just in New York, he said. “Everywhere I go, anywhere around the world now, anyone who owns offices says I’d like to lighten my load.”

Bob Knakal, chair of investment sales at JLL, told the pink ‘un “there’s a reckoning that’s going to come”. Over here? On Tuesday Citi Bank warned of a 38% fall in all London office values by 2025. A figure wise office holders should factor in to LTV forecasts.

Peter Bill is a journalist and the author of Planet Property and Broken Homes

No comments yet