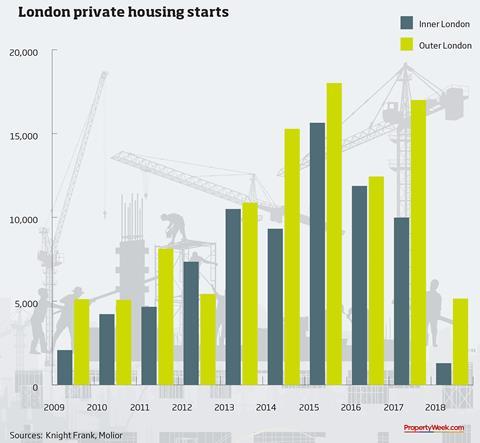

From 2009 to 2015, new-build housing starts in inner London enjoyed an almost undisturbed upward trajectory.

From a low of 2,080 in 2009, the market reached a peak of 15,728 in 2015, according to research from Molior London – the numbers suffered a momentary blip in the upper price bracket in 2014 thanks to the introduction of higher stamp duty rates. However, in 2016 new-build starts fell to 11,876 and in 2017 they slumped to 10,105.

So what’s to blame for the drop off in numbers and when will housebuilders start building in the capital again?

Following the global financial crisis, the revival of residential activity in London was largely credited to buy-to-let investors, many of whom were based in Asia and were less affected by the economic fallout than those in western markets.

This frenzy of investment activity drove prices to new heights and gave housebuilders the confidence to push ahead with new developments. But what goes up must come down and, thanks to several government cooling measures and a host of macro factors, starts, sales and eventually prices began to fall.

“It’s no surprise that the government’s cooling measures worked”

Ashley Osborne, Colliers

Arguably the first blow to inner London housebuilding after the financial crisis was dealt by the government’s reform of stamp duty in 2014, which raised the rates in the higher tax bands, and hit buyers of properties over the £1m mark hard.

Find out more – the latest on PW’s Call Off Duty campaign

“It’s no surprise that the government’s cooling measures worked,” says Ashley Osborne, head of UK residential at Colliers International. “As costs for buyers increased, the number of punters willing and able to participate in the market reduced and sales declined accordingly.”

Dampening measures

Osborne believes that the ’all buy-to-let investors are evil’ attitude adopted by the government influenced policymakers to devise a further set of dampening measures. The removal of tax relief for property investors buying houses to let out on an individual basis and the 3% additional stamp duty levy for purchasers of second homes had the desired effect.

“The government thought the space vacated by buy-to-let investors would be taken up by the build-to-rent market and the new white knights from large financial institutions would usher in the era of ‘the professional landlord’, but if you consider inner London, this simply hasn’t happened in a meaningful way,” adds Osborne.

“For many years, a significant part of residential supply in boroughs like Westminster came from changes in use from offices to residential”

Will Lingard, CBRE

With the gift of hindsight, however, the government may not have felt the need to enforce such measures. A swathe of market-disrupting events hit the London housing market hard not long after its interventions.

For example, permitted development rights, which were introduced in 2013 to boost the supply of homes, started to be withdrawn by some local authorities, including Westminster, around 2015 when office space began to grow scarce.

“For many years, a significant part of residential supply in boroughs like Westminster came from changes in use from offices to residential,” says Will Lingard, senior director in CBRE’s planning team. “This was cut off by planning policy changes and also the exemption of the Central Activity Zone, London’s core, from permitted development rights.”

Affordability vision

Sadiq Khan’s arrival at the Greater London Authority (GLA) in May 2016, and his vision to make half of all the new homes built in the capital affordable, added to the difficulties for housebuilders in inner London.

“In terms of bringing forward sites for development, the policy direction at the GLA, in particular its hardening position on affordable housing, notably reviews in section 106 agreements, has dampened the activities of the more entrepreneurial developers who are integral to the market,” says Charlie Hart, head of City and east residential development at Knight Frank.

Since taking office, Khan has put in place much stricter rules around the provision of affordable housing than his predecessor Boris Johnson. Khan’s policy stipulates that 35% of any development being brought forward in London must be affordable housing, rising to 50% for public land development unless developers can successfully argue the provisions make the scheme unviable.

“There is a view that the policy intentions, while laudable, are not functioning and are creating unacceptable risk,” adds Hart. “This has undoubtedly been a factor in declining starts, coupled with historic government cooling measures, Brexit and wider macro factors.”

“A competitive market has meant contractors have struggled to pass cost rises on to clients directly, so profit margins have come under pressure”

Dennis Hone, Mace

The Brexit vote, cast in June 2016, has clearly created uncertainty among investors, particularly overseas buyers, who are having to weigh up the attraction of a weaker pound versus concerns about how the UK’s decision to leave the EU will affect property values.

Dennis Hone, group finance director at Mace, says that on top of Brexit-related economic concerns and tighter regulatory controls, there has also been a steady increase in construction costs due to labour and materials inflation.

“Since 2016, we’ve seen prices increase by more than 10%,” says Hone. “A competitive market has meant contractors have struggled to pass all of those cost rises on to clients directly, so profit margins have come under pressure during that period.

Intervention

However, contractors cannot continue to absorb these costs and will inevitably look to pass them on at a time when residential sales values plateau. The same market forces will be affecting volume housebuilders as well as contractors. This may well be compounding the drop in housing starts.”

The combined effect of these factors has caused both pricing and sales to slow, according to Matt Sharman, head of the residential development and investment team at property consultancy Levy. “Consequently, developers, who are often backed by third-party equity, are having to work a lot harder to persuade investors of the merits of taking forward a new high-end residential scheme,” he says.

Given the cyclical nature of the market, many London property experts believe the government jumped the gun when it intervened.

“The government goes on about a ‘broken housing market’ but it sounds like the market has responded in exactly the way you would expect it to respond to outside intervention,” says Colliers’ Osborne.

He, for one, doesn’t believe such an intervention was necessary. “If the market had continued to rise and go unhindered, and the level of supply had continued on the same trajectory as it had been between 2009 and 2014, few would disagree that prices would have ultimately moderated,” says Osborne.

“You have to ask yourself: would you prefer a housing market where prices moderated due to a significant oversupply of new housing or a market where prices stayed flat with a slow pace of price growth because of a massive reduction in new supply due to external measures to cool demand?”

Regardless of how we got to the current point, many market experts are quietly relieved that the market has slowed down.“The fall in inner London starts is not actually a bad thing given that we saw such a large increase in starts in 2015-16, which are yet to complete, and will allow supply and demand to realign,” says Emily Donovan, associate director of Savills’ residential research department.

“With sales of units in inner London holding up, the ratio of starts to sales is back to around 1:1, the sign of a more normal, balanced development market,” she adds.

Opportunities remain

Sharman agrees. “The recent rebalancing has removed the unhelpful market-fuelled, private-equity-chasing unsustainable returns. While harder work than three years ago, opportunities remain.

“Looking across the broader market, there will be schemes that need to be re-planned in order to provide units that better meet with current market requirements. As ever, this is part of the continued process of producing a product appropriate for market demand at any point in the cycle.”

There is already evidence a new cycle has commenced. New-build sales in Q1 2018 were up 20% on the same period last year, according to CBRE, and there is optimism this will continue to improve.

“Cooling house prices will boost affordability in the long term, which should in turn lead to an increase in demand and therefore development,” says Lauren Ireland, sales director for IP Global. “Furthermore, greater clarity on the outcome of the Brexit negotiations will encourage foreign investment in London’s residential market.”

Following a prolonged period of government intervention, it looks like the market forces of supply and demand are set to regain control over London’s housing market again.

No comments yet